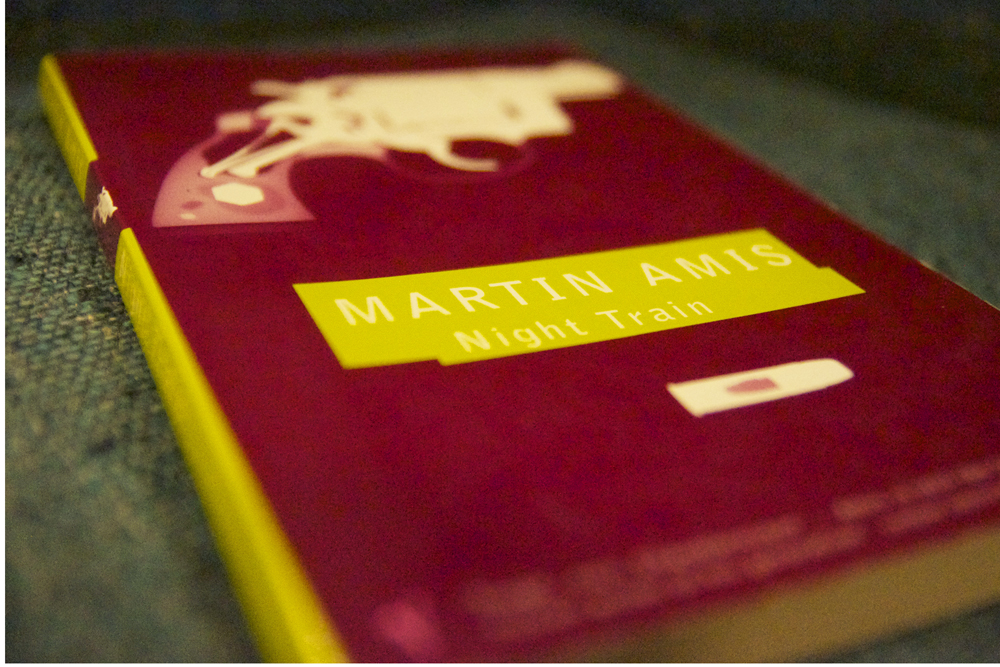

It was about eight at night, early July. The sun was blazing, falling behind the hills of southwest Portland. Sweat ran down my forehead. The dog was panting. Night Train by Martin Amis sat on my desk, open to a random page. Written in the style of Raymond Chandler, it is a short detective novel. Quick. Cynical. Heart-rending.

Coming in at just under 150 pages, Night Train takes the gritty skepticism of the noir whodunnit and turns it on its head.

What happens when an astrophysicist who has everything—looks, intelligence, money, love—is found in her bedroom with three bullets to the head? No sign of a struggle, no hint of homicide. But no sign of internal struggle either—no note, no signs of depression in her journal. So what happened?

That is the question police detective Mike Hoolihan asks herself when her mentor’s daughter, Jennifer Rockwell, is found dead. Hoolihan is sent to figure out, in typical Chandler fashion, the what, the who and the how.

Amis deviates from the typical detective script, though, and instead asks why. And he asks it in a funny way.

Hoolihan has made a career out of figuring out “hot potato homicides” and putting perps behind bars. Tag ’em and bag ’em, boys. Easy. This one, though, is a mystery. Why would a woman who seemingly has everything end her life? It just doesn’t make sense. Hoolihan starts focusing on Jennifer’s long-time boyfriend, Trader, as a suspect.

A jealous lover can usually solve a difficult case, but Hoolihan keeps hitting wall after wall. Trader and Jennifer, as far as she can figure, had no problems save maybe overactive sex drives. Then Hoolihan turns to a potential drug problem, but that creek dries up, and fast.

The more Hoolihan searches for the who, the more she comes up with nothing. Unlike normal detective stories, the who isn’t infuriatingly ambiguous—there are no suspicious people leaving town with suitcases full of money. The who is right there from the moment the police find Jennifer’s body in her bedroom. Three shots to the head. Suicide. So Hoolihan instead has to search for why the hell a brilliant astrophysicist, who by all accounts loves her life, would end it.

The answers, it turns out, lies in the Big Bang.

Night Train is asking: What is existence? Who created us, if anything? How were we created?

Jennifer, as someone who has dedicated her life’s work to finding these things out, is performing her own kind of whodunnit exploration as a scientist. As happens so often in noir, she goes to extreme lengths to find out the answers.

Jennifer’s story is bigger than run-of-the-mill human jealousy or a pedestrian run-in with organized crime. Her story balloons and reaches into the beginning of the universe. How did things begin? Why are we here? Amis transmutes the anthropocentric smallness of detective pulp into the vastness of the entire universe.

In usual Amis style, Night Train is equal parts playful and serious. Everything is just the right amount of absurd, including the stilted way people talk and think. You know that Night Train, though asking serious questions, doesn’t take itself so seriously, so you don’t need to either.

This book overflows with wordplay. “It’s half after five and she’s half in the bag,” Hoolihan says of one of Jennifer’s neighbors. Where existential crises tend to knock the wind out of a person, the playfulness of the language balances the serious nature of what Hoolihan is searching for and makes it easier to digest what Amis believes is the nature of the universe itself: absurdity and chaos.

Some find Amis’ wordplay gimmicky and distracting, as if good writing and good storytelling cannot coexist. But I think his fascination and experimentation with the English language are what make his writing successful. Most of the criticism of Night Train comes from the fact that it’s not your typical detective story. But it’s not supposed to be—it’s supposed to be a wholly different beast. It’s supposed to satirize how small the world is, how predictable.

Though there is chaos in noir, there’s always an answer. And there’s always a villain you can pinpoint. Even if the villain escapes, there’s still satisfaction to knowing whodunnit. That’s comforting for some people. The reason Night Train doesn’t work for some people is because Amis takes away that comfort. He takes away the illusion of finality, of the idea that there are always hard and fast answers. Sometimes we just don’t know.

If you’re looking for a run-of-the-mill detective novel, this is not the book for you. This book isn’t about murder. This book isn’t about being a police officer in gritty urban America. This is a book about the infinite smallness of human lives.