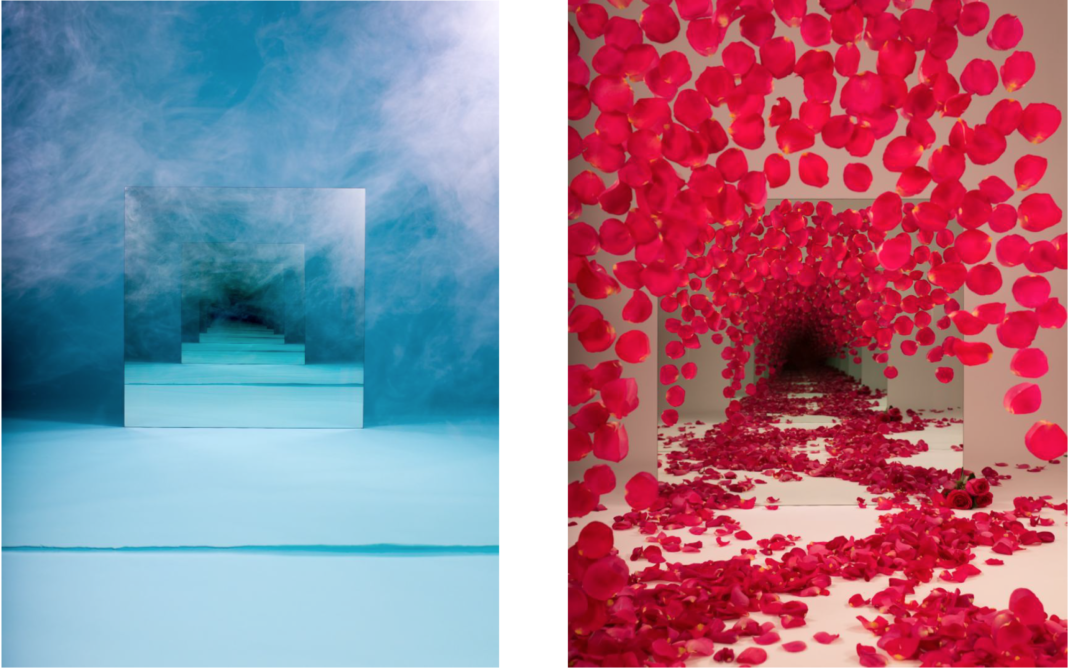

I experienced the virtual reality and short film exhibition Cloud of Petals, by the artist Sarah Meyohas, at its Portland opening reception on Dec. 2 with the comedian Chris Ettrick. I arrived during the reception’s last half hour, so I didn’t get to watch Cloud of Petals (2016) in full. I wanted to be sure I could experience the virtual reality component, and I found the three VR headsets I tried on (a fourth wasn’t working) fit over my large, thick glasses with ease. According to the original exhibition statement from the digital artist Tyler Pridgen, the VR component is composed from artist team’s labor in plucking and documenting 100,000 rose petals. The photographs were uploaded to a neural network, which used them to learn how to infinitely generate unique petals.

The majority of Disjecta’s vast exhibition space was used to create a dark screening room for the film while a row of VR headsets hung from the ceiling outside of the projector’s beam. The VR experience within the third headset reminded me of the 2009 Sony/Thatgamecompany video game Flower, where players guide floating petal streams across different meadows. Cloud of Petals viewers watch red, yellow, pink and white roses petals. Cloud of Petals is intentional in its use of roses, whereas Flower’s levels are not strongly defined.

The first headset places the viewer in a dimensionless all-black environment, an infinite rose petal cascade being the only stimulation. The cascade is realistic enough that as I tried physically approaching it, I experienced vertigo. In my efforts, I accidentally ran into the woman in the headset next to me a few times, but while on-site volunteers helped place and remove the headsets, none of them tried stopping me from running into other viewers. I heard a camera shutter, and couldn’t tell if this was Disjecta’s staff documenting my experience, or Chris trying to shame me on social media. I removed the headset and moved to the third one.

Viewers in the third headset guide a petal cloud, which stirred petals partially coating the “floor.” It is the headset most similar to Flower. I didn’t think to check if the cloud responded to eye movement, because my eyesight needs such high correction that I don’t instinctively use my peripheral vision. When I moved my head in different directions at varying speeds, the cloud and the simulation’s music changed in speed and composition: Speed turned the cloud’s shape into the floral version of the ‘Oumuamua interstellar object, or resembled a moisture cloud when slowed. Likewise, at a standstill, the music played softly and slowly and picked up vibrance as the viewer changed course and velocity.

The second simulation was supposed to respond to the viewer’s ocular and hand movements, but when I waved my hand before my eyes, the simulation barely responded. This simulation was most similar to the third, where the viewer is on an established plane covered in petals. At points, the petals and music swelled together like waves. Feeling the simulation was out of my control, I allowed my eyes and body to relax, in the same way I relax when viewing rapid-movement text animations, like works by the Web art group Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries. I experienced a euphoric rush as I took in the softly ebbing music and the free-floating, three-dimensionally twirling petal snow. While I normally experience high anxiety in public, I let my guard drop and felt safe in the shapeless petal chamber.

Knowing my time was limited, I removed the final headset and moved to the makeshift theater’s front row to watch the movie. The non-narrative film uses documentary and arthouse tropes. Set to a dramatic score composed by a musician named Drew Brown1, Cloud of Petals mixes scenes documenting the physical and intellectual labor that made the project, along with scenes that might represent the project’s digital labor, like scenes where a fly crawls across a pixelated screen. There are also symbol-rich but aesthetically cliche images, like rose blooms burning on their stem, or ultra-glossy snakes slithering across the petal-strewn floor of Bell Labs, the facility where Cloud of Petals was created. The score uses more brass and slightly darker, more brooding tones than the VR experience.

Cloud of Petals’ images, their placements and interactions are all chosen for how many meanings they can have. Square shapes, for example, are used prominently throughout the film (or, again, as much of the film as I saw in less than half an hour): they are the tiles in Bell Labs’ floors, they are the cards on which the individual petals rest when they are photographed, they are the pixels making up the surface display on which the fly walks, they are the very Disjecta projection surface through which the viewer experiences half of the project. The square is also seen in plastic hallway coverings whose material physicality resembled the skin of a slightly dehydrated flower petal.

Bell Labs is an architectural character, symbolizing not only its scientific history and mid-century modern design achievements, but as a space that marries art to its innovative history. Bell Labs was the site of at least one Nobel Prize–winning discovery, to say nothing of other crucial but less prestigious works or its residential-commercial communities of the past. Bringing femme symbology into a structure associated with masculinity, or femme exclusion, can allow for femme contributions to science to be recognized, as with the scientist Vera Rubin’s contributions to discovering dark matter, the actress and inventor Hedy Lamarr’s contributions to communication signals that birthed Bluetooth and Wi-Fi, or the mathematicians Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson’s contributions to NASA’s Project Mercury, to name only a few (sorry, Marie Curie).

The fly can represent presence of human, organic non-human and digital intelligences—the former being the person operating the computer’s mouse that tries clicking on the fly, the latter being the science that sends optic stimulation to the brain for interpretation. The fly occupies space between the viewer and the digital realm and makes the viewer aware of layers; this particular significance reminds me of the artist Rose Dickson’s short film Nothing Between Us (2016) when it screened in her Slow Mask exhibition at Portland’s Melanie Flood Projects last fall.

The burning rose not only represents emotional states like heartbreak, but also planned obsolescence, violence, chemistry and impermanence. High-gloss or other highly textured animals are especially popular in visual art associated with contemporary fashion’s past and upcoming season; it will be interesting to see to what extent this trend becomes associated with Cloud of Petals as both age.

Snakes and roses also have special queer significance in recent years: see also, how the social media–based fans of drag queens Alaska Thunderfuck 5000 and Valentina used the respective snake and rose emoji to represent the pop culture figures on digital communication platforms in negative and positive, sincere or ironic contexts, or the differences in which Alaska 5000 and Taylor Swift responded to the snake emoji being imposed on their respective artistic brands’ social media accounts.

Cloud of Petals also contains room for the viewer’s unique interpretations: A sequence where men threw loose rose bouquets off of a high balcony, which eventually cuts to a long bird’s-eye shot of a woman I believe to be Meyohas lying on her back among the petals, seemed to mirror the brutally homophobic violence of the terrorist organization ISIL/ISIS/Daesh whose members recorded themselves throwing accused homosexual men off of buildings to their deaths as crowds of people witnessed the physical and psychological horror.

Most importantly, everything visible in Cloud of Petals relates to how to visualize digital constructs like neural networks, storage clouds and the paths by which information travels to and from storage. The movement of the snakes, whose heads were moving in autonomous directions but whose bodies were still uncoiling from each other, reminded me of the ways search engines pour across raw data for return queries, for example. Each rose petal can be anything in the digital sphere: a pixel, a website, an mp3 file, etc. As a site for world-changing scientific and technological developments, Bell Labs’ symbolizes more than its biographical history: It is a physical storage space for physical-as-digital data.

The ultimate effect achieved is that Cloud of Petals creates a new common language for viewers of mixed experiences with aesthetic language to engage, either with the exhibition or with each other; for indeed Cloud of Petals would be a different experience if it had no social aspect. The curator Julia Greenway, Ettrick and I all have different education and exposure levels when it comes to contemporary art, fashion and film, but the three of us were able to find something within the exhibition to discuss as the night came to a close.

The worst aspect of cliche is when cliches make their viewer groan; they are even worse when they are employed for the sake of being recognizable, but no further effort to connect that recognition to other concepts or meanings (see also: almost all late ‘00s parody movies). Even though I am an angsty gay man, I groan at art about angst that doesn’t explore the concept further than what it personally means for the artist, or gay art that does little more than document the artist’s ideal beauty standard. If there’s no consideration for anyone else in the aesthetic experience, why do I, the outside viewer, care if a film uses snakes (penis!) and roses (vagina!) to symbolize masculine and feminine energy?

Successful art contains multiple paths for interpretation without meaning any old thing. The cliches used in Cloud of Petals aren’t the most original images in aesthetic expression, but they are used masterfully and effectively to visualize the processes of organic and digital visualization and allow for new ways of knowing to bloom.

1 It has not been confirmed whether this is the composer Drew Brown, who also performs in the pop-rock band OneRepublic.