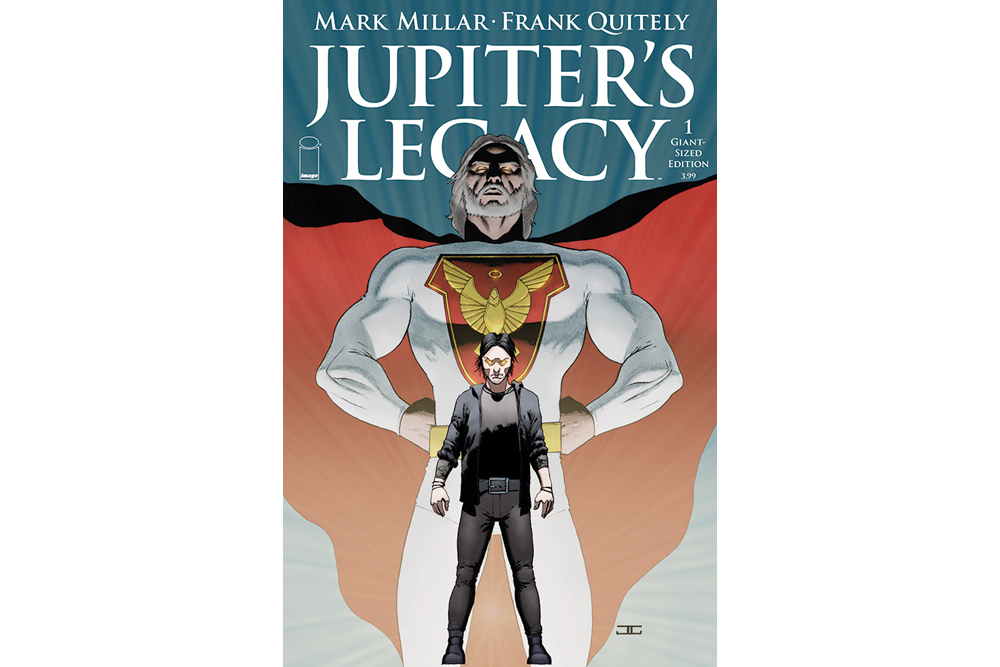

What happens in the generational divide between superheroes and their progenies? That’s exactly what the comic books Jupiter’s Legacy and Jupiter’s Circle are about.

The first volume of Jupiter’s Legacy has just been released in tandem with the premier of its prequel series, Jupiter’s Circle. Both series were written by Mark Millar, of Kick-Ass fame, and follow a group of people from the moment they get superpowers, at the outset of the Great Depression, to the moment of their demise.

Legacy is mostly about these superheroes’ children: Brandon, an alcoholic club-hopper, and Chloe, a Buddhist and vegetarian philanthropist who keeps overdosing.

These kids are definitely screwed up, on the long path to therapy and always mobbed by the public eye, ignored and talked over by their super-powered parents who pulled America out of the Depression by being able to fly and shoot lasers out of their eyes.

Brandon and Chloe are hardly ever sober. But even if they were, how can they ever compare to parents who were heroes in World War II—parents who had an unambiguous nemesis? You can fight Nazis, you can encourage banks and people to put money in the economy, but how do the disenfranchised fight disenfranchisement?

The layers in this comic are really what sell it because not only is there the relationship between young adults and their parents (which is rocky to begin with), but there’s also the relationship between the generation of young adults today and companies like Marvel and the legacy of the golden age of comics.

We’re always being compared to past generations and falling way short. Our air isn’t as clean, our houses aren’t as cheap and we can’t live on the same minimum wage. These superheroes are even worse than the baby boomer generation because they’re the baby boomer’s parents, so the generation gap is even more abyssal.

The series asks questions about our relationship to the superheroes who popped up in the golden age, characters whose entire characterizations are interwoven with World War II, like Steve Rogers as Captain America.

Before he became Captain America, an early superhero name for him was literally Super American, and while we might still have some platonic notion of “American,” we also recognize that it’s not only a fantasy, but a nightmarishly nationalist one.

While Captain America is, to this day, punching Hitler in the face in 3-D, he’s not fighting real monsters anymore. White supremacy is still a huge issue in America, but the mainstream Captain America is fighting H.Y.D.R.A. and space monsters. Not exactly the racists we see today or widespread unemployment.

Jupiter’s Legacy explores this problem. Brandon and Chloe’s father is literally the Utopian, who refuses to touch the economic, social or environmental issues that threaten us after facing the Great Depression—and I’m assuming Hitler and the Axis Powers—in his prime.

His prime was a golden, wonderful, mysterious age easily romanticized from the 21st century, but that’s exactly where Jupiter’s Circle comes in. Was everything really like this older generation said, or are they too subjective, too biased to accurately report?

Jupiter’s Circle follows the parents of Jupiter’s Legacy and explores not only what the world was like but also what they and their friends were like.

We see Richard Hutcherson, famed supervillain, as one of the group’s inner circle, a close friend and family member, while he struggles with a triple life, born out of the desperation and prejudice of the world tinted beautiful by people’s memories.

He’s always spoken of as the great betrayer, as the worst supervillain that the world has ever seen, but, really, history is written by the victors and is unintelligible

to new generations.

I hope they address issues like race and gender in Jupiter’s Circle, but so far the way Grace, Utopian’s wife, comes across, I’m not going to get my hopes up.