In 2011, a wave of uprisings spread through the Middle East as demonstrators protested against regimes with long-standing human rights violations, including political corruption, state violence, social inequality, high unemployment rates, food inflation, restrictions on free speech and undemocratic systems of government.

This wave, popularly known as the Arab Spring, began with the people of Tunisia and soon spread across much of the region including Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Syria, Iraq and Yemen. While Tunisia is generally considered to be the only success from this movement, many countries saw authoritarian rule emboldened or regimes succeeded by civil war.

Two countries in particular, Syria and Yemen, remain entrenched in conflict with no end in sight. In 2017, directors from United Nations Children’s Fund, the World Health Program and the World Food Program declared Yemen as having the worst humanitarian crisis in the word. Thousands have died as a direct result of the conflict; however, that does not compare to the hundreds of thousands of suspected cholera cases. Additionally, about 7 million people are experiencing famine, and 60 percent of the population is food insecure.

Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh stepped down in 2012 in response to the uprising, leaving the country with an uncertain future.

Dr. Robert Asaadi, an adjunct professor of political science at Portland State specializing in Iranian politics, explained how this conflict accelerated into a larger regional dispute between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

“We saw a re-emergence of what was an older conflict between Houthis in the Northwest of the country and the Sunni Arab population that is dominant elsewhere,” he said. “That’s accelerated, and basically since 2015, Yemen has descended into a state of civil war. Just like we’ve seen in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan [and] other weak or failed states in the region, it becomes like a vacuum and then dominant players in the region, namely Iran and Saudi Arabia, are intervening on both sides.”

According to Asaadi’s understanding of the conflict and Iranian relations, Saudi air strikes as well as Saudi Arabia’s involvement elsewhere contribute to regional instability, which in turn negatively affects Iran. “Iran is concerned that Saudi Arabia is trying to expand its influence and basically make a network of client states on its borders,” he said. U.S. support for Saudi Arabia further complicates the matter, provoking Iran to counteract.

On March 6, PSU’s Middle East Studies Center hosted the lecture “Understanding Yemen” with political science professor Dr. Peter Bechtold as part of their month-long series discussing issues in the Middle East. During the lecture, Dr. Bechtold, whose extensive career has focused on Middle Eastern politics, stressed Yemen’s geography and topography as crucial issues in the government’s lack of central control.

Mountainous villages can be extremely remote, and modern infrastructure like water, electricity and roads are often inaccessible to build or maintain. Tribes have traditionally mediated disagreements through delegates in a process known as peace huts or sulh, Arabic for reconciliation or compromise. These delegates would come from each side of the disputing tribes to a neutral village and negotiate until reaching a resolution. “That was the traditional way of doing things because the government was far away,” Bechtold said. “It was also incapable and arguably incompetent.”

President Saleh became president after his predecessor Ahmed al-Ghashmi was assassinated, and he would remain in office for 33 years until the Arab uprisings in 2011. Bechtold explained that in the midst of these protests, sharpshooters were placed on buildings and the situation quickly devolved into violence. The government response in Yemen was similar to that of Syria, in which security forces opened fire on demonstrators.

Though Syria arguably receives far more media coverage than Yemen does, Bechtold called the Syria coverage “horrendous in the Western world, whether it’s PBS or BBC. In Syria now, 60 percent is under government control, 30 percent under the United States and the Kurds. We have no Arab allies in Syria, but we don’t talk about this in public because it’s inconvenient, and our media strangely simply go with the government lie.”

When Western media do portray the Yemeni conflict, it’s often in the context of relations between Sunni and Shia Muslims. Asaadi refutes this narrative. “I actually don’t think that’s a particularly relevant or helpful way to think about the conflict,” he said. “It’s much more motivated by this problem of state weakness and powerful actors in the region intervening to promote their strategic interests.”

Remnants of American-made cluster bombs have been found in various parts of Yemen, as reported by Human Rights Watch and The Intercept. Under the United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs, cluster munitions are illegal under international law. These munitions owe themselves partly to U.S. arms deals with Saudi Arabia, the largest of which was signed last year and amounted to $110 billion.

In a recent attempt to end Saudi support and U.S. involvement in Yemen, Sens. Bernie Sanders, Chris Murphy and Mike Lee submitted a bill that would give Congress more power in withdrawing troops and overriding the president on acts of war.

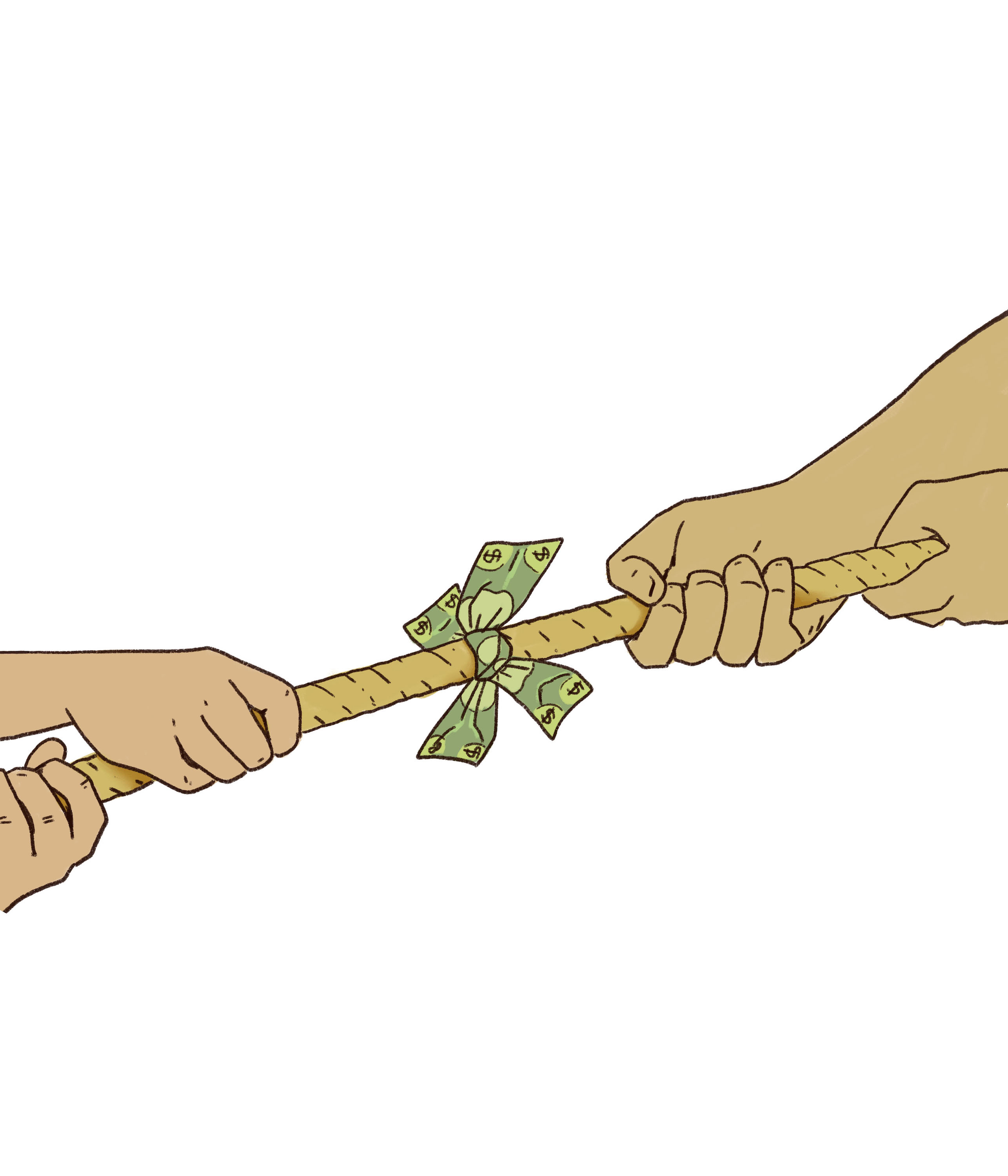

Saudi Arabia continues to implement aid blockades to prevent badly needed supplies from entering the country. “The Kikuyu people of Kenya have a proverb that ‘When elephants fight, it’s the grass that suffers,’” Asaadi said. “In the last 15, 20 years, who’s been dying in these conflicts in the Middle East? It hasn’t been predominantly Iranians and Saudis, it’s been Afghans, Iraqis, Syrians and now Yemenis.”