The organization Disarm PSU dropped a banner over SW Broadway stating “Did PSU Disarm? NO!” on Wednesday May 12.

“With the banner drop, Disarm PSU calls on Portland State University to make good on their promise to disarm our campus police,” stated Disarm PSU in a press release the same day. “We also want to make sure all members of our community, including prospective students, are not duped by false advertising and know that the PSU campus police officers are still patrolling with guns.”

The Campus Public Safety Office website states, “In August 2020, CPSO Chief Willie Halliburton announced that campus police would begin unarmed patrols at PSU during fall term of that year.” For some, the announcement meant demands for CPSO to disarm its officers were heard and that there would be an impending change in policy. However, when CPSO had to postpone disarming in fall 2020, celebration slowed and discourse grew.

“What [the announcement] sounded like was that they were disarming,” said Disarm PSU and Childhood and Family Studies faculty member Miranda Mosier. “I think a lot of people took it that way and certainly a lot of folks who have been working on this for years and years and years were celebrating.” For Mosier, the goal for the banner drop was to draw attention to the process for disarming CPSO officers.

“I understand the frustration of no further updates about unarmed patrols,” said Christina Williams, Director of Media and Public Relations. “We are meeting with Chief Halliburton regularly, but hiring and training officers, rewriting hundreds of pages of policies and establishing new operating agreements with Portland Police Bureau are complicated processes that take a great deal of time. There are very few examples of sworn law enforcement agencies that have made the decision to patrol without arms, and none in Oregon. As a result, we [PSU] are really creating something completely new.”

The website also states that as of January 1, 2021, Halliburton and his Lieutenant, Joe Schilling, have begun regular patrols without firearms, further extending the original deadline.

The announcement explains the extension by stating, “It was an ambitious timeline, and it has been delayed by many factors, including police officer turnover and a complex process for rewriting policies and agreements. Chief Halliburton and the leadership of PSU remain committed to this groundbreaking shift in campus policing.”

According to Williams, prior to 2014, CPSO at PSU were not armed. In response to what is known as “Kaylee’s Law”— which passed in 2019 and is named after a student from Central Oregon who was murdered by a college security officer in 2016—CPSO altered their patrol protocol.

“The passage of Kaylee’s law in 2019 completely changed the landscape for campus security, and makes it impossible for PSU to return to the pre-2014 status quo,” Williams said. “[Kaylee’s Law] resulted in a complete overhaul of the statutes governing campus security officers.”

Out of this “overhaul” came a growing discourse regarding campus safety between students, faculty and the Board of Trustees. Disarm PSU was created out of these conversations.

“This army has a really long history now,” Mosier said. “My experience and understanding of Disarm really started in the fall of 2014 when the Board of Trustees was first formed and they were holding this special series of meetings to discuss the possibility of arming.”

Mosier said that in those early conversations it was clear the majority of the campus community was against arming CPSO. However, it was apparent that PSU’s president at the time, Wim Wiewel, was in favor of the new protocol. On Nov. 24, 2014, the BOT moved forward with the decision and CPSO officers were armed the following spring.

Four years later on June 29, 2018, Jason Washington was shot and killed by an armed CPSO officer. When this happened, Disarm PSU came to support Washington’s family and continued to pressure CPSO about disarming.

“It was an intense and emotional time,” Mosier said. “Hundreds of folks would fill these Board of Trustees meetings demanding that CPSO disarm. The university’s response was disappointing to a fair amount of people.”

PSU contracted a group called Margolis Healy to conduct a campus assessment of policing. The final report recommended more policing on campus and justified keeping CPSO armed. However, Mosier suggested there were “objectively true methodological flaws” in the way the assessment was conducted such that the evaluation criteria were biased towards protecting police officers.

Coincidentally, on the day that the BOT decided to arm CPSO a grand jury acquitted police officer Darren Wilson for the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

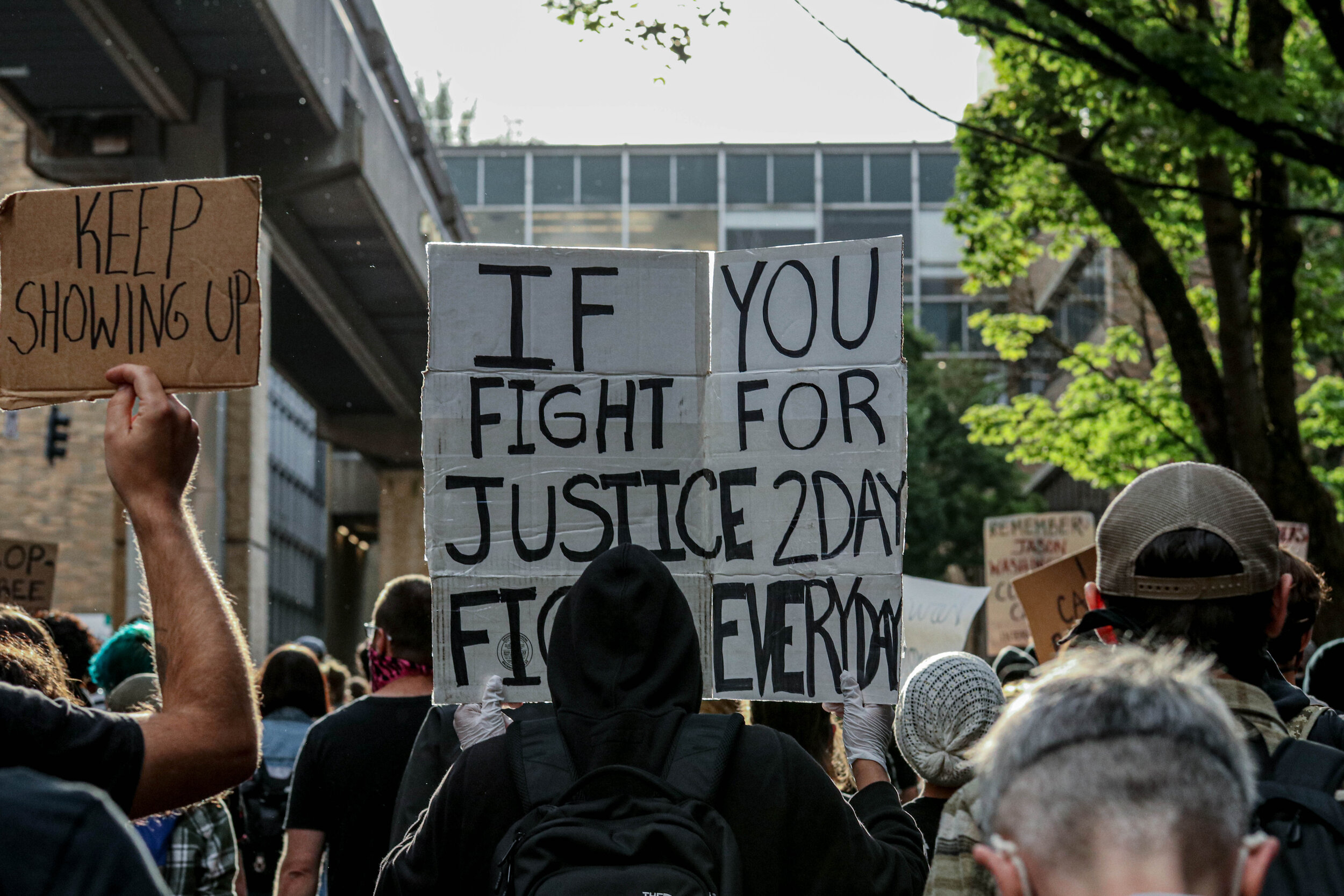

“This was all kind of taking place in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement and just this growing awareness of police brutality towards people of color,” Mosier said.

Seven years later, in the wake of another prominent time in the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, not much has changed. Although awareness of police brutality has become a more integrated part of conversation, CPSO has continued to arm its officers.

“In June 2020, I remember President [Stephen] Percy putting out a statement in support of Black Lives Matter like lots and lots of leaders,” Mosier said, “but I would say the majority of the departments on campus said, ‘You know, that’s great, but we need to disarm. We need to show Black Lives Matter by disarming.’”

According to Mosier, the group met to detail what “disarming” at PSU means and what it looks like in practicality. They came up with three specific demands.

The first is called “reverse.” This demand asks for the reversal of the decision made in 2014 to arm CPSO. Mosier noted this is intended to remind people that PSU existed for a long time without arms and this decision to be armed only came about seven years ago. There was a time when CPSO was not armed and it is possible that they can be disarmed again.

The second demand is “reinvest.” Disarm PSU asks for the reinvestment of funds from CPSO to other organizations and programs on campus. Building on the quantification of resources going to arming CPSO, “reinvest” focuses on how those resources could be redistributed to programs on campus that are underfunded.

Lastly, the group came up with the notion of reimagining what safety on campus could look like. This demand highlights the possibility of other resources to help students feel safe on campus outside of CPSO.

Collectively, reverse, reinvest and reimagine ask for a deconstruction of CPSO into services that provide campus safety, but no longer rely on police for it. Although centered around the priority of disarming CPSO, these demands work to help the PSU community as a whole by reshaping the allocation of resources to departments and programs that are underfunded and creating a safety plan that centers around the needs and sensitivities of students, according to Mosier.

Moving forward, Disarm PSU is focusing on the future of the PSU community, especially with the intentions for in-person classes this upcoming fall. They plan on keeping the conversation going and making sure resources are available to students and faculty.

“Thinking about transitioning back to campus and those alternatives, and then memorializing Jason and also pushing the university to make sure that they keep those promises seems critical now,” Mosier said.