1950s England. The Russian War is over. The Soviets have been destroyed by their own incompetency. Satellite countries have risen up and destroyed the sickle and hammer with help from the Allies, and now peace has settled across the land. Or so you think. There’s deception, espionage, intrigue. There’s double-crossing and military…stuff.

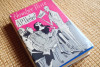

If you think I just described an alternate universe in which the Cold War ends in the mid-’50s, you’re right. If you think it’s some action-y thriller or some such nonsense, you’re wrong. It’s the tongue-in-cheek novel Number Nine (or The Mind-Sweepers) by A.P. Herbert.

A.P. Who-bert, you may ask?

Though he was wildly popular in his lifetime, you’ve probably never heard of him. He’s one of those writers who undeservingly faded into the the ether after his death. But when he was active, he had a cult following comprised mostly of other writers like P.G. Wodehouse and J.M. Barrie—that guy who wrote that thing about never growing up.

Herbert was a really cool guy who was freakishly good at everything he did. Born in 1890, he wrote poetry, drama and fiction pretty much from the time he was born to the time he croaked. He was a frequent contributor to the humor magazine Punch, whose contributors’ list included Sylvia Plath and Somerset Maugham, among others.

Herbert, though, was so much more than a writer.

He attended Oxford and graduated with first class honors in Jurisprudence, which, like, whatever, probably isn’t really that big of a deal. I went to the University of Oregon, but you don’t see me bragging about it. He was also a reformist member of Parliament for a couple of decades, because why not?

Homeboy helped reform the divorce laws in the 1930s—he’s the reason English people don’t need proof of adultery to say peace to their spouses. He also loved the river Thames more than a man probably should, and fought to help conserve it. What a guy.

Number Nine, originally published in 1951, is the story of some guy with the long-winded name Admiral of the Fleet the Earl of Caraway and Stoke, his son, Lieutenant the Viscount Anchor—also known as Anthony—and his attempt to wrestle the family home, Hambone Hall, from the Civil Service’s cold, bureaucratic hands.

You see, Civil Service has taken control of Hambone Hall—so named because the third Earl of Caraway and Stoke hit Oliver Cromwell over the head with a hambone, thus starting the Restoration. It’s being used as a psychological testing facility and, even though the Earl and his son don’t exactly use the home, they want it for themselves. Because aristocracy.

Recently returned from the front lines of the Russian War, Anthony heads to Hambone to help his father. They enlist a girl named Peach to help them, and madness ensues.

The writing is the kind of stilted, “I say, old chap” stuff I imagine British people say all the time. The ol’ dust-up! H.P. sauce! What a willying wobbly-boo of a day, eh? That kind of stuff. It’s over-the-top silly and just the right level of critical. Herbert’s criticism is so sharp that he even dedicated Number Nine “to our long-suffering Civil Service.” Ouch.

Herbert is a master of several things, not least of which is satire. Number Nine is just one in a long line of humorous novels he wrote in the first half of the 20th century on the social, economic and legal landscape of England. These books were so well-written that people often mistook them for true stories. But, as a great satirist is wont to do, there are over-the-top signposts that tell the reader this isn’t real.

I mean, let’s be honest here. Oliver Cromwell getting hit over the head with a hambone? Ham wasn’t even invented until the Industrial Revolution.

Anachronisms aside, Herbert’s writing is sharp, over-the-top and timeless. Number Nine is laugh-out-loud funny. You’d be foolish not to read any Herbert you can get your hands on. And when you do: tongue meet cheek, and enjoy.