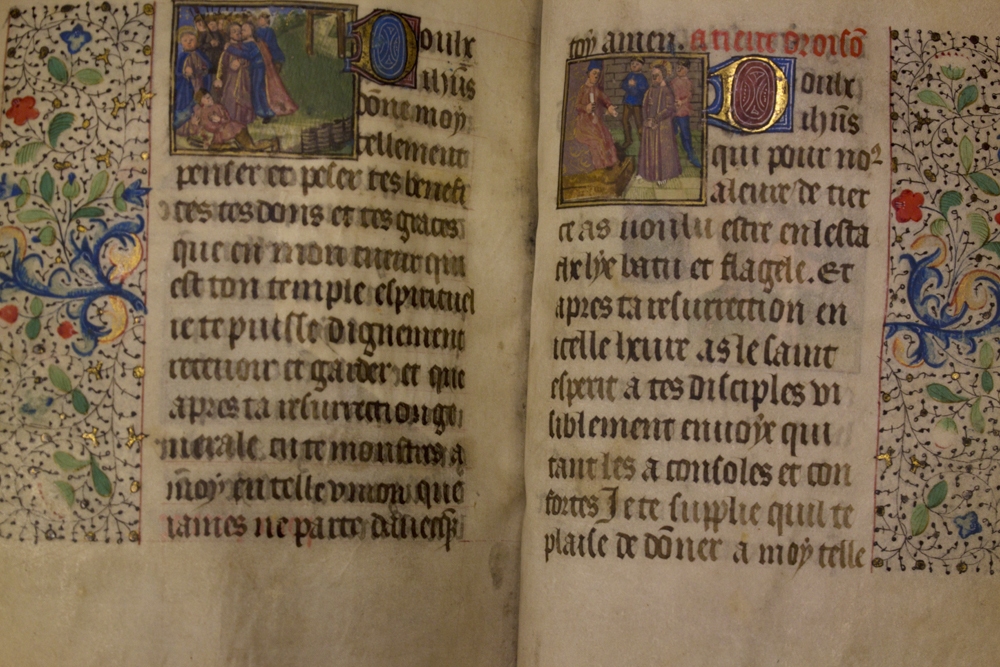

Pass by the elevators in the Branford Price Millar Library and you might notice a curious array of ancient texts and the tools used to create them. Nestled discreetly among this display is a little book, perpetually cracked open so that a single ornate, colorful page is prominently displayed.

That book is a book of hours, and it is the library’s first full, medieval manuscript acquisition—or in more easily digestible terminology: a medieval book. The exhibit is the result of an art history seminar conducted over winter term and led by Professor Anne McClanan.

The story starts further back than that, though.

“It’s taken a year of planning,” McClanan said.

The library’s special collections department acquired the book in May of 2013, and McClanan was instrumental in selecting the text.

Books of hours are Christian religious texts, and common in the world of rare book dealers. At one point it was more common to own a book of hours than it was a Bible. As a result, books of hours have significant teaching value.

“If you’re teaching art history, a lot of the images are of things that kings owned,” McClanan said. “This testifies more to the material culture of a wider spectrum of the population.”

Over the course of the 10-week seminar, 12 students were tasked with analyzing the book of hours from multiple perspectives. Once their analysis was done, they designed and organized a physical exhibit, and even produced a series of short podcasts for digital exhibition, based on their respective areas of study.

Those areas of study include everything from marginalia—the illustrations, colors and symbols often found in the margins of medieval texts—to the chemical makeup of the materials used to create the book of hours.

Mysterious origins

Shirleanne Ackerman Gahan, a senior majoring in art history, studied the origins of Portland State’s book of hours.

“The popularity of books of hours is still kind of astounding,” Ackerman Gahan said. “They were really popular, and a lot of people had at least one. It’s cool it think that people had these books and that they were really treasured, special objects.”

For many people, a book of hours wasn’t just precious—it was their only book.

“It’s cool to think of a whole family sharing this one book,” Ackerman Gahan said.

Because books of hours gained popularity in an era before the printing press, each one is handcrafted and unique in its own way. Wealthy patrons would sometimes opt to commission their own customized versions and would sometimes include their family’s coat of arms, inscriptions or portraits.

Details like these help to narrow down the identity of the previous owner. Many books of hours, though, are more standardized and feature sparse customization. Such is the case with PSU’s copy.

While the university’s book of hours is light on customization, there are a few clues that point to— if not the exact owner of the book—at least class-standing and region. The presence of two additional prayers and the absence of additional customization indicate that the original owner of the book was Parisian and likely not of noble birth.

Despite the details, the identity of the initial owner of the book of hours remains a mystery. In the world of medieval manuscript analysis, though, that’s not surprising.

“I was mostly expecting there to be a lot of loose ends,” Ackerman Gahan said. “Obviously, I would be thrilled if I was able to find more distinct information. Since I had researched books of hours before, I knew I wouldn’t be able to find some things.

“Sometimes research leads just come to a dead end.”

Preserving words

A common misconception about religious texts from the Middle Ages is that they were made by monks, diligently pecking away at page after page in remote monasteries. In actuality, by the 15th century, books of hours were sold by artisans on popular shopping routes in large cities and were often produced alongside teams of apprentices in workshops.

These artisans would grind down materials such as cinnabar or azurite to create pigments. Preservation of medieval texts can be further ensured by knowing what went into their creation. If a conservator knows the materials used, he or she can work on a chemical level to maintain them.

“One way of determining how best to care for materials is to discover what they’re made of,” said Carolee Harrison, special collections and conservation technician at Branford Price Millar Library. “Once you know something about the chemical properties…then you’re able to learn about how best to protect it and make it last for the future.”

Preservation of historical texts like books of hours can be problematic.

In the 19th century it was common practice to sell individual manuscript pages taken from full texts, the reason being that several single pages, called leaves, could be sold at a higher price than a whole book.

The book of hours acquired by the university is missing three pages. While it’s unknown where exactly those pages ended up, it’s reasonable to assume they were removed for individual sale. Their removal would also indicate that the pages were illuminated; a richly decorated page would fetch a higher price.

“We want to have those [rare materials] available for people come and study, view and learn more about the time that created them and the people that created them,” Harrison said.

“Having a complete book really puts it in context.”