When I was a kid, I thought that the only people who listened to classical music were either very old or pretentious. I associated classical with the mellifluous if entirely inoffensive sounds of Mozart and Beethoven—composers whose work evokes crashing waves, gorgeous sunsets, aristocratic tea parties, and the ringtone on your grandparents’ landline. To my immature palette, it always just seemed like simple music masquerading as high-brow and emotionally complex.

This started to change when I was in high school. I became friends with someone whose actual name I won’t print but whose initials were “J.S.B.”—the same as Johann Sebastian Bach’s, a coincidence he absolutely relished. That’s because he was obsessed with Bach and specifically Glenn Gould—the renegade Bach interpreter who came under fire from the old guard for humming along to the piano on his recordings. J.S.B. owned two pianos and there was a bronze bust of Bach’s head on one of them. He is still one of the greatest musicians I’ve ever known, and he was only 16 years old. He did those initials justice.

Through this friend I developed a newfound appreciation for classical music. I gravitated toward Bach and other Baroque composers the most, because that was usually the type of classical he put on burnt CDs for me. During my senior year of high school, I became more interested in progressive rock and other athletic forms of music and requested a crash course in experimental classical from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, since I knew this era of the genre was a touchstone for classic prog bands like Yes and King Crimson. He gave me a mix featuring pieces by Igor Stravinsky, Philip Glass, Arnold Shoenberg, Erik Satie, John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and more. In my pursuit of a certain elusive aural fucked-up-ness, I was getting into harsher and harsher music. I finally found it in the form of experimental classical.

I am no longer a kid. I am now very old—29—and pretentious. When I get up in the middle of the night to use the bathroom I feel like I’m wearing sandbags, and when I perform a physical task as menial as reaching over my shoulder to grab the seat belt I feel as if my back is being crushed by a bronze bust of Bach’s head. True to my nature, I have sold most of my indie rock albums for a modest collection of video game soundtracks and classical records. Like Larry David I have come to loathe the timbre of the human voice—I’m trying to get back in touch with my high school roots as a tireless seeker of fucked-up music.

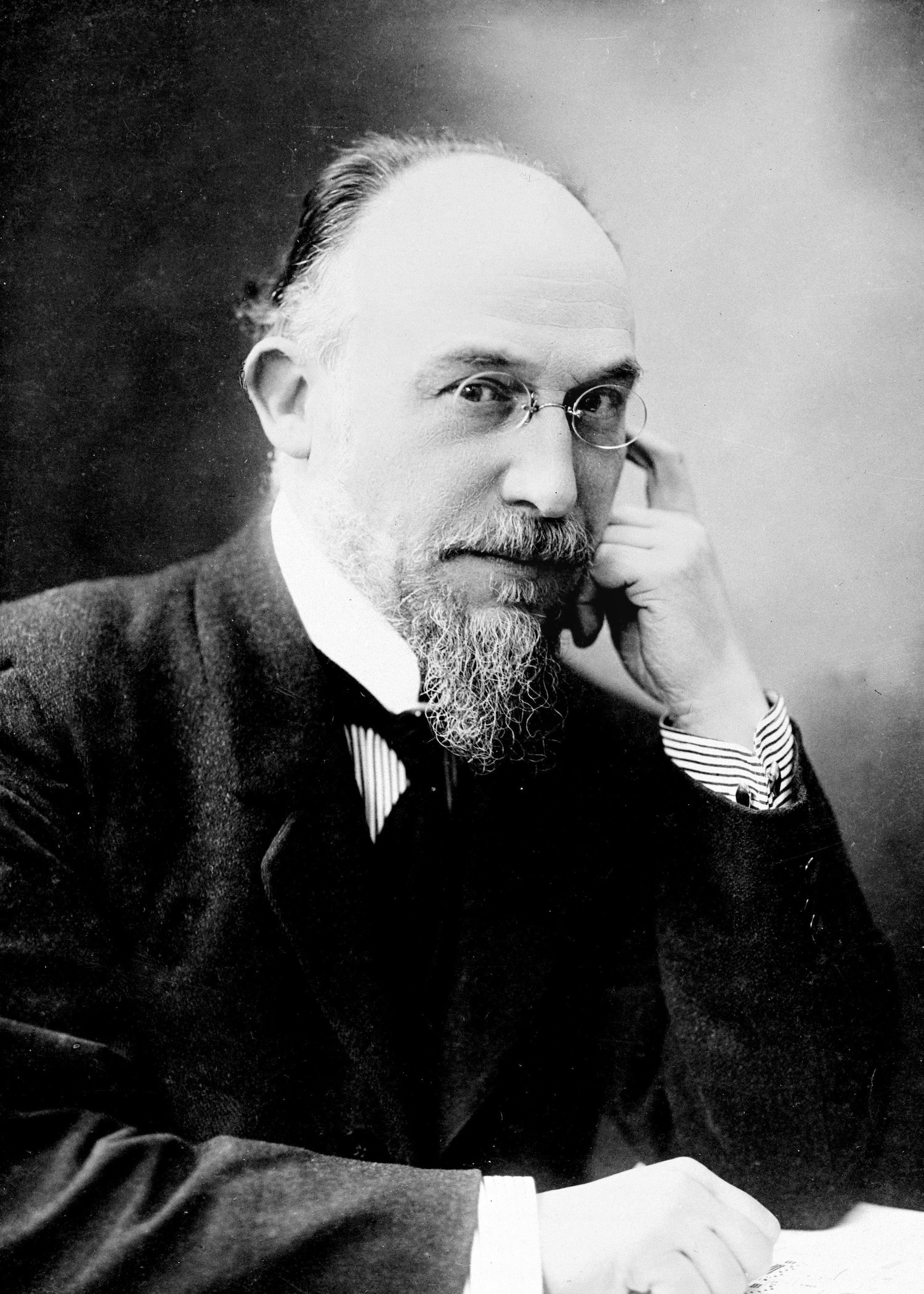

One of the aforementioned composers—French composer Erik Satie—is perhaps more deranged than the rest. You’re probably familiar with his gorgeous and comparatively conventional “Gymnopédie No. 1,” but that’s not all there is to Satie.

My partner is a big Satie-head, so we listen to a lot of furniture music, or musique d’ameublement, around the house. In fact, she was the person who turned me onto proper furniture music. Sometimes you’ll see art critics use the term “wallpaper” pejoratively—this likely has its origins in the term furniture music.

But what is furniture music, you ask? In essence, it’s the music you hear in the elevator or in the doctor’s office waiting room. Satie’s furniture music, specifically, was a prototype of sorts to lounge or Muzak—it’s music designed for passive consumption that requires absolutely no cognitive engagement from the audience in order to be appreciated. In fact, cognitive engagement is explicitly discouraged.

The more you pay attention to furniture music, the creepier it becomes. It is repetitive, minimalist and punctuated by tiny moments of dissonance. It’s the soundtrack to waking up from a dream within a dream for eternity. And I am obsessed with it.

I’m usually against conflating aspects of an artist’s personal life and their art, but a little bit of background on Satie’s eccentricities really does seem necessary here. He hoarded umbrellas and carried a hammer with him wherever he went; he loved moldy fruit and boiled wine; he founded his own religion; his performance piece Parade—which featured contributions from Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau—started a riot and resulted in his imprisonment.

Like most of the canonical European modernists whose artistic naiveté was destroyed in the first world war, Satie had a real philosophical agenda that he attempted to incorporate into his art. This is perhaps why he didn’t even identify as a composer or musician—he claimed he was a “phonometrographer” which, in typical Satie fashion, is basically meaningless and is at most synonymous with the terms musician and composer. When Satie premiered furniture music at a Paris art gallery in 1902, he begged prospective audience members not to come; during other performances, he supposedly berated the audience for “listening” to the music being performed. Again, according to the tenets of furniture music, listening wasn’t the point.

Despite Satie’s arbitrariness, a lot of his furniture music holds up on its own, even divorced from its high art underpinnings. It is often creepy and funny, sometimes gorgeous, and always maddeningly repetitive. It’s unique for extreme music in that it’s gradually taxing—it’s the musical equivalent of physical exercise.

But when you do consider its deep, philosophical underpinnings, Satie’s furniture music seems more profound and prophetic than ever. We live in an era when furniture music has a financial stranglehold on the music industry in the form of official Spotify playlists curated by a cabal of superficial AIs. It’s the future that Satie anticipated, but probably not the one he desired in earnest. Anyone who’s ever listened to a Spotify playlist can tell you how languid and aseptic the music usually is—it’s like Satie’s furniture music only without the humor, critical self-reflection, chops, or aesthetic sensitivity. Spotify’s playlists are overwhelmingly tailored to environments and scenarios that do not call for challenging art whatsoever—coffee shop studying, late night chilling, drives to the beach. It’s merely wallpaper and no one ever has to be reminded not to listen.