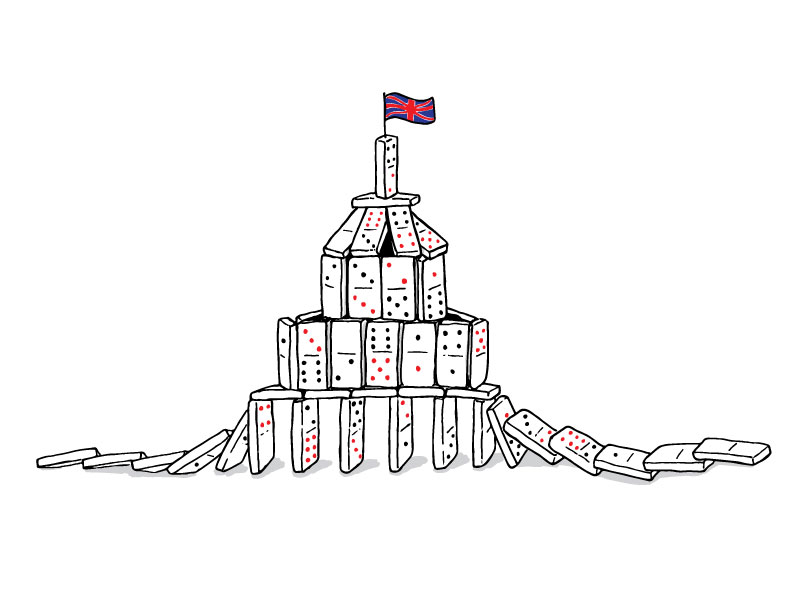

In unprecedented fashion, international political possibility has shifted toward the left. Jeremy Corbyn’s rise in the Labour Party resulted in a domino effect of radical political opportunity across Europe. The Overton Window—the space upon which citizens consider political feasibility—has opened toward the left despite dominant neoliberal and conservative governments.

This rise can most neatly be understood as reactionary populism. The same populism that allowed Donald Trump to be elected and Bernie Sanders to gain mass support has come in the wake of failed neoliberal policies and public distrust of current leadership models. Wealth gaps, taxes and ecological sustainability have caught the attention of the public eye throughout the continent, and it is the Labour Party which inspired new faith in the ability for government policy and regulation to actually be effective.

As Richard Seymour emphasizes in his Corbyn: The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics, this is not Tony Blair’s Labour Party, nor is it a radical communist revolutionary mutation. Gone is the neoliberal politics of fiscal conservatism and homeowner’s rights, a la the Clintons and Bushes. Instead this party is moving toward structural, economic change.

The Labour Party model for European politics is primarily a movement to allocate funds and taxes in a more responsible fashion than the current neoliberal model, and it represents a stepping stone to a direct social democratic structure of governance. To put it bluntly, this model represents a politics of better management and trust entirely predicated on current European political leaders’ inability to win over the masses amidst corruption, scandal and international tension.

The Guardian reported the right is “flitting between having to make the case all over again for neoliberal ideas which, until recently, were seen as facts of life, and conceding ground to Labour—in rhetoric if not in substance—on policies such as tuition fees and council housing.” The continental ripple effect of Labour’s rise amid the failure of neoliberal policy has forced moderate parties across Europe to swerve to the left on certain issues or risk defending policy that has popularly been understood to be ineffective.

The leftist in Italy

The dominoes fall in Italy where the leftist Five Star Movement has risen to public prominence on a self proclaimed anti-establishment platform and advocacy for immediate implementation of direct democracy. Echoing the Labour Party’s objectives, The Five Star Movement runs on a platform of ecological sustainability, job growth through technological industry and an overhaul on the allocation of public funds to support public welfare. The Five Star Movement candidate Luigi Di Maio comfortably leads the polls as of mid-February, beating out Forza Italia and Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s four-time prime minister. In combating the Five Star Movement, moderate parties and conservative parties like Forza Italia have had to resort to appealing to public trust, and they have completely avoided debating policy. The recent elections across the Western world can attest to this political strategy: Simply insisting on neoliberal policies is not politically effective.

The Greek Party

The reformist, anti-establishment tactics of both Corbyn and the Five Star Movement depend on the combination of public disillusionment with establishment, centrist politics and the willingness of powerful economic players such as corporations and fiscal policy makers, to support a change in the state’s system of governance.

On the other hand, there is the problem of Greece. The Greek party Syriza benefited from a similar populism of leftist opportunity, but since then, its national economy has dramatically failed. It is important to make the distinction between what Corbyn is inspiring across Europe and the failed venture that Syriza set out to accomplish.

Corbyn’s rise to power within the Labour Party, a party that has veered toward the right for quite some time now, came about as primarily a tactical move of influence and corporate accommodation. Populism is important, but to be successful within a neoliberal government, Corbyn has shown that a leftist political agenda must be able to gain support from the outside—namely, from moderate politicians and corporate stakeholders, which Greece could not do. This tactical method of infiltrating popular political discourse has enabled Corbyn to catch the current UK political establishment off guard and this strategy is gaining influence across borders.