BANG! POW! BOOM! Comics in the United States are full of onomatopoeias that emphasize action. In addition, our comics encourage the reader’s participation with fun but unrealistic hero stories that focus almost exclusively on fast-paced intrigue.

It is pretty fair to say that due to the culture of the United States, we yearn for instant gratification. In both literary and cinematic art, we demand that it entertains us and that we can relate to it—but not too much. We demand that it allow us to see another person’s struggles without seeing our lack of response to those struggles.

While comics in the U.S. are impressive in their own right, Japan has taken a different route in some of its literary and cinematic art. Their art asks for the consumer’s empathy and relation to the everyday struggles of every person, including members of society that are often outcasts.

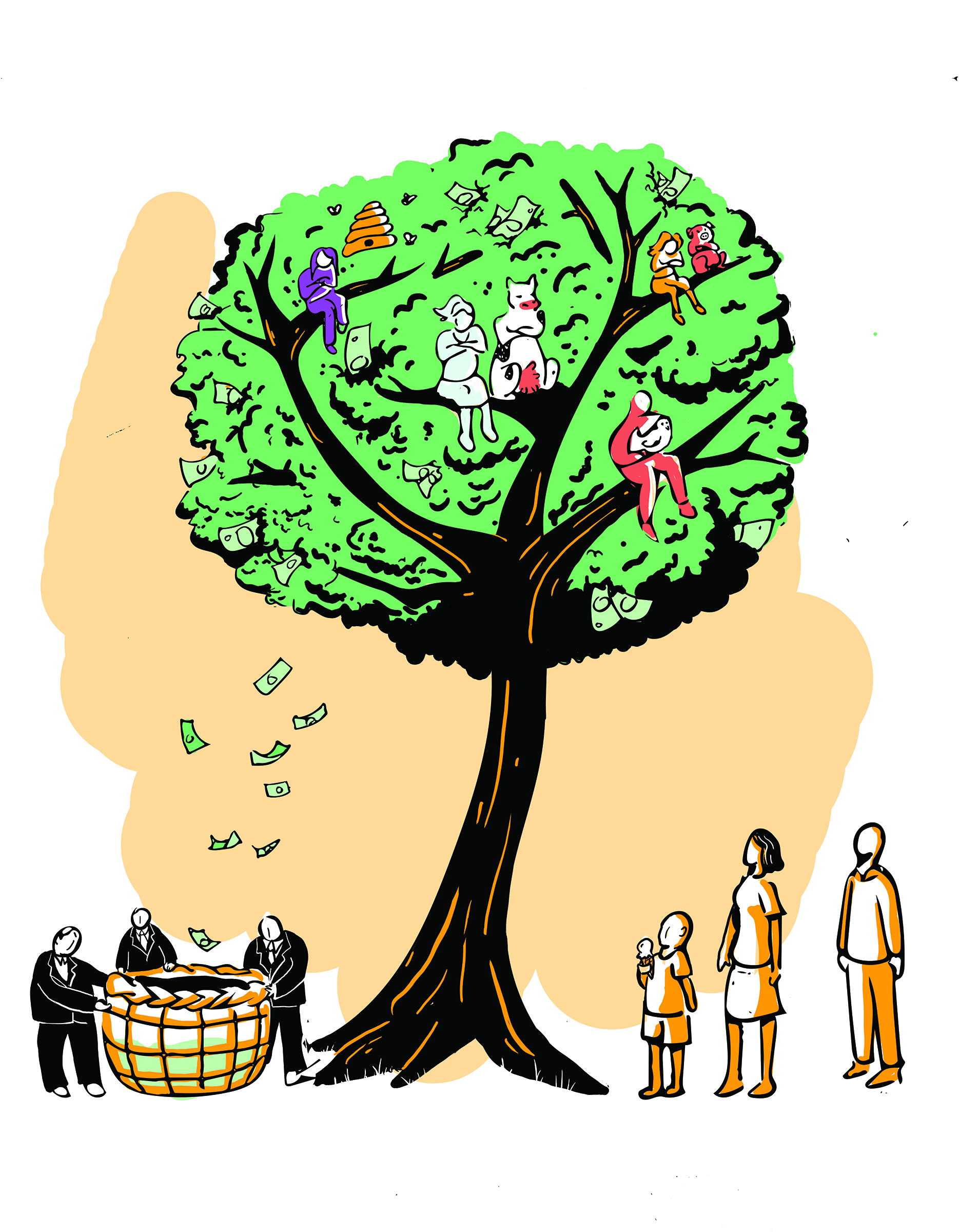

Houselessness has been a pressing issue of modern culture for centuries, and how each culture seems to deal with it varies widely. According to the Japanese Advocacy and Research Centre for Homelessness, there were at least 3,392 unhoused people in the entirety of Japan in 2017, although some nonprofits that work with the houseless think that number could be two to three times higher.

Either way, if one looks at Oregon alone, which is 1.5 times smaller than Japan, the houseless population is 15,876 as of 2022—a significant difference. When something is more visible, people will inevitably be more likely to complain about it, and this can very quickly lead to discrimination, stigmatization and an overall lack of empathy.

On the other hand, peoples’ perspectives are both consciously and unconsciously affected by how art portrays others. Comics in particular have a way of pulling the reader into the story. Scott McCloud, well-known comic expert and author of Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art called the cartoon a vacuum that pulls in our identity and awareness.

“We don’t just observe the cartoon, we become it!” McCloud wrote.

While it can be fun to live vicariously through fictional characters like Spiderman or the Hulk, their stories teach us little to nothing about regular struggles. Instead, comics in the U.S. gloss over everyday things and often rush on, never lingering on the things that make us human.

Japanese manga is often the opposite of this. While the story can include action and intrigue, it also glorifies normal experiences just as much, if not more.

Disappearance Diary by Hideo Azuma is one manga that meaningfully portrays the Japanese respect and glorification of everyday life. In this manga, we follow the author’s story as he walks away from his life as a manga artist and his family to be houseless.

Japanese houseless people may have chosen to be houseless because they want freedom—it is not necessarily related to income, addiction or mental health as we might see in the U.S.

Professor of Japanese Language and Literature at Portland State University Dr. Jon Holt recently gave a talk on Disappearance Diary. A possible reason that some Japanese people chose the freedom of being houseless is that “they felt a lack of connection with their families or work, so [they] decided to make their own life paths,” Holt said. One could definitely see this portrayed in Azuma’s personal story.

One can see an illuminating perspective of houselessness in the nitty-gritty aspects of how Azuma portrays himself in cartoon form—the monotony of searching for cigarette butts to smoke off the ground, the frustration from being constipated because all he had to eat for a while was radishes, the struggle to protect himself from the elements at night and the pure joy when he found good food during the day.

“The daily life of a houseless person—the daily life of an unemployed person—can be true art, true entertainment, or both for the Japanese,” Holt said.

Lack of empathy for others often comes down to ignorance. However, manga, like any comic medium, demands that the reader become the character, thus experiencing houselessness without actually experiencing it.

While houseless people in Japan still face their fair share of prejudice and discrimination, Disappearance Diary helps shape more positive perspectives. By comparison, we in the U.S. constantly fail to see the beauty in everyday struggles. Instead, we fight to get through them, and we definitely do not want to see it in our art. “We are allergic to the everyday,” Holt said.

While houselessness may continue to persist for centuries to come, art can become a vital tool in positively shaping perspectives. In the United States, we must learn to accept and revel in the everyday. We likely will never be able to shoot webs out of our hands or turn into a giant green monster when we get angry, but we can learn to see ourselves more clearly when artwork encourages the reader to slow down—and look at their existence and the existence of others.

Consuming art that demands empathy for the other strongly encourages one to demand empathy from themselves, and leads to more acceptance and appreciation for all of life’s struggles. We must embrace the mirror because, if we do not, we will not only be missing out on some of the most extraordinary art ever made, but we will also continuously fail to see the flaws in the way we see and treat others.