As a species, we are poised at the brink of a transformation unlike any before.

The ancestor of this coming metamorphosis was not political or philosophical in nature; it did not emerge from the ashes of the American Revolution or the Bolshevik’s, nor did it germinate from the teachings of Jesus, Buddha or Muhammad. The predecessor to the singularity we so boldly march toward was something far more primordial, far more tangible.

It was industrial.

The last three industrial revolutions transformed the fabric of human civilization: The first, borne of steam and coal, powered newly invented machinery and catalyzed both demand and consumption on every continent; the second, characterized by steel and electricity, forged a future of mass-production and assembly lines, the internal combustion engine and the radio; the third, marked by the proliferation of computer technology and the dramatic introduction of the internet, digitized the world and enabled unprecedented technological collaborations.

On the brink of this “Fourth Industrial Revolution,” challenges arise which have only been imagined in science fiction, along with questions posed to a collective humanity whose answers will determine the rise or fall of human societies. While technological and financial globalization has further connected a world of distinct and disparate peoples, our inequalities, once thought solvent by our earlier industrialization, continue to deepen.

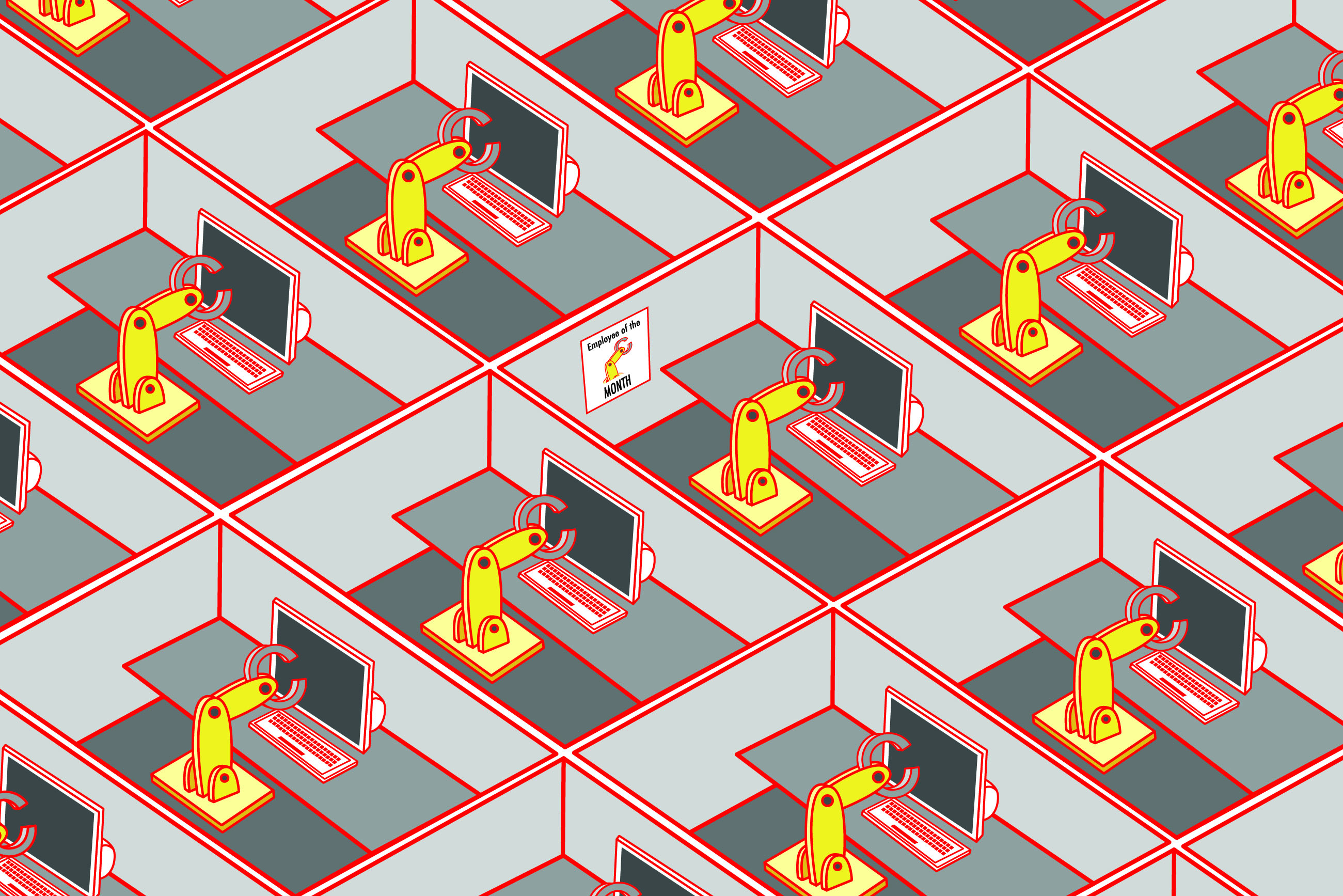

In the past, automation was believed to create more jobs than it replaced, but as artificial intelligence expert Nils Nilsson of Stanford University puts it, “This time is different.” While previous innovations sought to disrupt markets, the coming culmination of breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, biotechnology, robotics and energy sciences will not merely interrupt global trade—they will revise the very composition and constitution of human civilization. This time around, we will not be able to escape the long-asked and now urgent inquiries into the structure of civil society, the nature of our governments, and the necessity of a social floor.

The rupturing of entire sectors will lead to a phenomenon known as technological unemployment. Historically, supply-side economists have used this concept to advocate for lower or abolished minimum wages, whereas labor unions and proletarians on the other side of the table have become increasingly anxious about their share of the pie. A report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has shown that since the 1980s, while the conventional split of profit is around a 2:1 reinvestment allocated between labor and capital, labor’s share of the pie has begun to shrink. Through automation, labor costs can be offset, if not entirely substituted, by capital.

Exacerbating the coming challenge, the institutions designed to protect labor and consumer rights (FCC, DOJ, FTC, SEC, etc.) have done an absolutely miserable job. Corporate mergers and acquisitions have consolidated entire markets into a handful of unbelievably powerful mega-corporations—what happens when these corporations, with the capital necessary to invest in automation, create an entry barrier so high that no small business could ever compete? Ten companies control virtually everything we eat and a mere six own more than 90 percent of American media: Are we naive enough to believe that profit-driven companies have any incentive to self-limit their productivity or growth for the sake of the worker?

The scale at which we discuss this issue is global: Economically, the Fourth Industrial Revolution is expected to be labor-replacing. What will we do when 50 percent of workers—an optimistic estimate—become unemployed by the end of the century? Coupled with the virtual promise of catastrophic climate change, it becomes increasingly clear that our political systems are outdated, perpetuating an unsustainable and even obsolete manner of governance and living. Our true political challenge will be balancing automation and environmental protection while ensuring rights to all, so that all may flourish under this new era of hyper-productivity. If capitalism’s path is trimmed towards sustainability and humanism in the coming economy, it could be considered the victory of capitalism, with all being afforded basic income and a chance to better the world. Should we fail? The poor will be left to rot, millions will be born into unthinkable environmental decimation, and class struggle will boil into constant violence.

Labor’s Extinction Event?

MIT professors Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee argue that the coming revolution poses an exponential threat to millions, if not billions, of human beings. Optimistically, a supply-side technological dream come true could potentially create a utopian “end of work” scenario, with humans free to pursue non-routine activities, laborious only if desired.

Unfortunately, the short and sanguinary history of the human species suggests it probably won’t go this way. Never-before-seen advancements in a wide spectrum of collaborative technological fields will fundamentally change our way of life—but for whom, specifically? As robots replace workers faster than our economy can bear, a universal basic income, coupled with a strong and totally reformed education system, could do a tremendous deal for promoting equity. If such steps aren’t taken, we will quite literally leave half of the human race behind, punishing them for not studying computer science at a prestigious university.

The first wave of automation is already upon us, with Oxford Martin School’s Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology reporting that 45 percent of America’s occupations will be automated in the next 20 years. If you think it’s only low-skilled labor that will be replaced, you’re in for a nasty surprise. Automation has already been deployed in the legal profession and the medical field, with some studies suggesting that 80 percent of what doctors do could be automated by advanced diagnostic analytics and supercomputers.

The price of computing is falling—rapidly. Companies that pay a zero percent or lower effective tax rate continue to invest in automation, all while public infrastructure crumbles and millions are without access to health care. It begs the ultimate philosophical question of our economy: Is it for the consumers or the shareholders? Beyond that, we have spent far too long moralizing capitalism; with the planet and the worth of human life facing existential threats, the coming Fourth Industrial Revolution must arrive simultaneously with a moral and civil revolution against international greed.

Rage with the Machine

As wealth is decoupled from work, like productivity from employment, we are faced by unique political questions and challenges. So what, then, do we do? MIT’s Erik Brynjolfsson suggests we race with the machine rather than against. Instead of taking the path of the Luddites—19th century English textile workers who destroyed the machinery that threatened to replace them—we need to do the opposite.

Pitting proletarians against technological progress will do nothing but inflame global conflict and entrench oligarchs, providing justification for the continued replacement of labor and for wage suppression. Instead, we ought to capitalize on the rapid growth of wealth and income by revolutionizing not only our institutions of labor but all of our social institutions. With the nature of work accelerating towards machine intelligence, we should invest in educating a new generation of leaders for the new global economy. In line again with Brynjolfsson’s thinking, human beings need to complement themselves with computerization—we quite literally have no other option.

The Lifespan of Human Labor

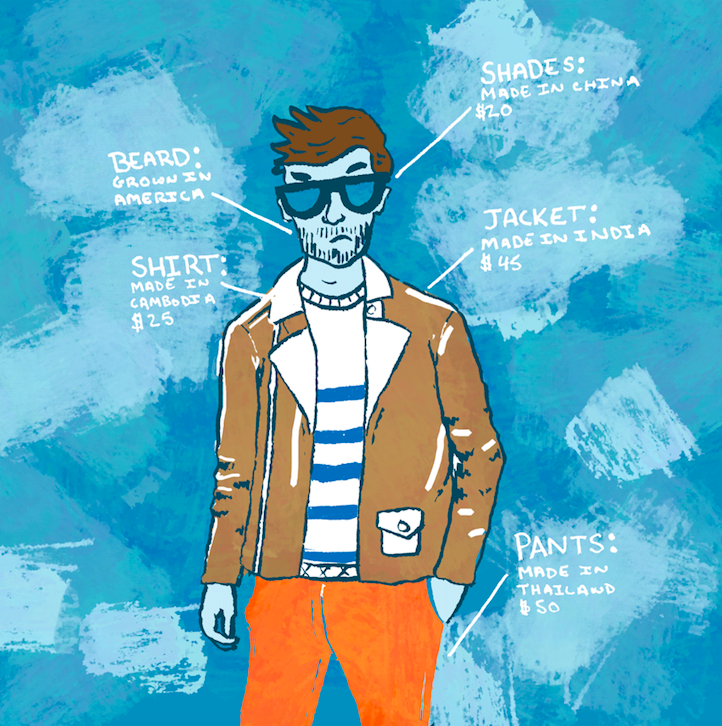

Economic nationalism, a relatively nationalistic belief in theory, was a point even taken up by the ever-popular Bernie Sanders. In layman’s terms, it describes a policy of economic protectionism, restricting the movement of labor and implementing tariffs and taxes with the intent of promoting domestic prosperity. Unfortunately, the nationalistic element that this concept preys upon finds its foundation in a divisive us vs. them ideological framework, wherein the value and prosperity of human life is contingent upon their nationality.

The election of Donald Trump is evidence enough of the liveliness of American nationalist populism, which stakes itself on an identity claiming victimization by the movement of labor out of the United States. Much to the dismay of partisans and demagogues on both sides, labor movement out of the country will seem like small potatoes next to the coming wave of robotization.

The national identity that serves as a bedrock for political action and movement has long been perpetuated by an oligarchic cultural and political elite, who, like all in the electorate, claim that their policies have helped grow American jobs. This election alone has shown the return of economic nationalism as a publicly solvent position—but what happens when the very underpinnings of nationalism unravel?

Our own nationalities and the economic anxieties that constitute them will soon be outflanked by an identity shaped by the common experience of robotic replacement. Bickering about jobs outsourced to other nations is pointless: Whether you’re an American, Chinese or Mexican manufacturer, the person who will ultimately replace you won’t be a person at all.

Trade deficits make working-class citizens furious. Seeing millions of manufacturing, tech and electronic jobs leave the country in all 50 states has set off a nationalistic powder-keg. It’s another classic example of workers being set upon one another, blaming foreign powers for the decisions of private sector heuristics and our own congress. If you’ve decided to hate another race or nationality of people because you think they stole your job, you might want to stop burning that bridge. In the future, nationalistic division of labor will seem ridiculous. Robots aren’t naturalized into nationality, and the companies that own them often operate internationally.

Better yet is that machines, as far as we can ascertain, don’t strike or protest. Unless the coming revolution is managed carefully, workers of the world might not even have their chains to lose. President-elect Donald Trump’s promise to bring manufacturing jobs back from China and Mexico are unfulfillable: By the time his protectionist agenda begins affecting the economy, companies will have already started dumping capital into automation and replacing the need for low-skilled human labor with versatile automation.

Creating two distinct nations in the United States is a tangible possibility: One would be rich beyond belief, trained, educated and employed; the other, a vague shadow of past generations, poor, unemployable, suffering from a newfound human obsolescence.