Burning Man founder, former Portland State student and Oregon native Larry Harvey died at 70 on Saturday, April 28. Harvey suffered a serious stroke on April 4 in his San Francisco home, which left him hospitalized, according to a statement from the Burning Man Project.

Like me, he was adopted and formally worked as a bike messenger and landscape architect. I worked for Burning Man in the communications department as a member of Media Mecca.

My only interaction with Harvey was in 2016 in First Camp behind Media Mecca. He walked by looking for someone. I couldn’t help him, but another member of Media Mecca did. He walked away, and that was it. But that doesn’t mean Harvey didn’t affect my life.

The organization’s employees, volunteers, members of the media and scores of Burners helped me in my personal and professional life in ways they will never know. The location of Black Rock City, Nev.—the temporary city of 70,000 where Burning Man happens—introduced me to geography and locations that would have otherwise remained foreign to me. The philosophy and ideology of Burning Man and, by extension, Black Rock City helped me develop as a citizen, friend, husband and student.

So why would any sane person spend time and treasure going to the worst place on earth to camp with no running water, trash cans or electricity? What would drive someone to volunteer to do backbreaking work—or the comparatively cushy work I do in media—in a landscape actively trying to kill everything on it?

The answer requires having dusty feet on the ground of that dry lakebed in northern Nevada. To answer that is to realize the answer is as simple as it is complicated. We didn’t follow Harvey blindly; he’s not a cult leader. Burning Man isn’t a religion.

The Associated Press described the Burning Man event as “an esoteric mix of pagan fire ritual and sci-fi Dada circus where some paint their bodies, bang drums, dance naked and wear costumes that would draw stares in a Mardi Gras parade.”

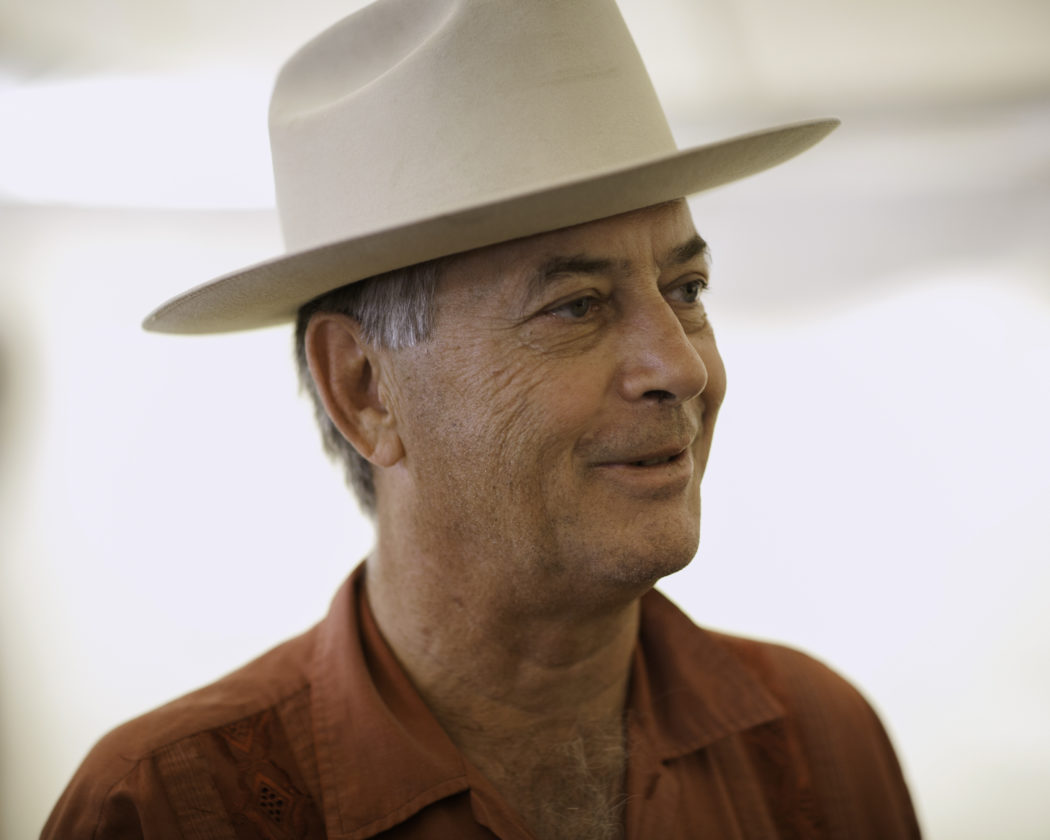

Harvey was just a man with faults and doubts like any of us, but what he did do was show us what we’re capable of when we strip away the veneer of capitalism and selfishness and live in the moment; when we focus on making things and participating for the benefit of ourselves and fellow humans, instead of climbing a corporate ladder or padding a bank account. He had a spontaneous idea to burn an effigy—and the wisdom to not tell anyone exactly why—and 32 years later, we’re mourning the passing of the man in the Stetson with the rest of the Burning Man community.

Harvey is survived by his son Tristan, his brother Stewart, his nephew Bryan and a global community of devoted Burners inspired by his vision to build a more creative, cooperative and generous world.

I wish I had the chance to get to know him as well as others had, but I’m not at all upset about the chance to live in the world he created.

I’m a returning student after a 17-year break in my education. During that break, I worked as a photojournalist in New York, Connecticut, New Jersey and Texas and served in the U.S. Air Force as a public affairs specialist. I am now a senior majoring in communications with a minor in photography. This is my third term as the photography editor of Vanguard, which is my second time in four schools working as a photography editor for a student newspaper, both of which earned multiple awards for excellence. I am responsible for the photographic content of Vanguard, both print and online, as well as educating photographers in the field of photojournalism.