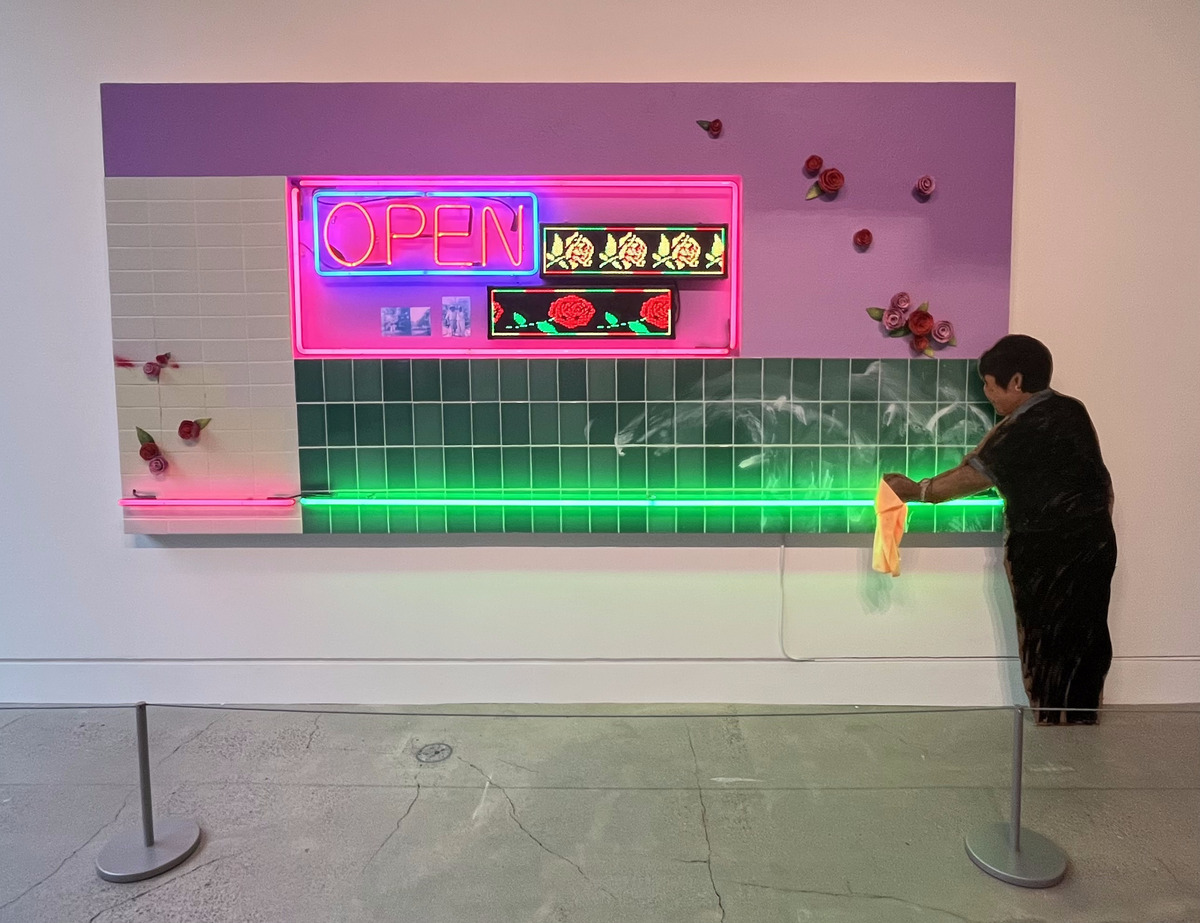

A large mural framed by neon light and sculpted roses at the gallery entrance of Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at Portland State (JSMA at PSU) immediately draws the eye. Underneath a bright open sign, a couple of old photos—which look straight out of a family photo album—are on display amid the otherwise alluringly synthetic scene.

Labor of Love is currently on view at JSMA at PSU, an exhibition showcasing the works of numerous local and national contemporary artists. Labor of Love aims to feature and expose the unacknowledged or unappreciated labor practices of marginalized or underprivileged people. It includes a wide range of art mediums, including sculpture, painting, print work, video art and found art.

Los-Angeles-based Artists Patrick Martinez and Jay Lynn Gomez titled their piece “Labor of Love,” much like the exhibition was for them.

“Something I find really beautiful about this [piece] is that you can tell that the neon is fading the images,” said Anna Kienberger, JSMA at PSU’s Program and Outreach Coordinator. “A visitor made a great observation that, with time, it’s going to fade even more with the neon, kind of representing that over time, it will become more and more hidden.”

Gomez has a few paintings displayed throughout the exhibition. One of these pieces depicts a reclining woman—seemingly a maid or cleaner—resting on a bed in an all too familiar composition. The imagery resembles the goddess Venus as portrayed in the sixteenth-century oil painting “Venus of Urbino” by the Italian Renaissance painter Titian.

Similarly, French painter Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” is a nineteenth-century painting known for replicating Titian’s “Venus of Urbino.” However, instead of a goddess, Manet depicts a sex worker in that exact reclining position. By referencing these historically iconic paintings, Gomez is, in a way, questioning who exactly is allowed representation in the art world.

Gomez’s work displayed in Labor of Love centers essential workers rarely seen in these painting styles. These subjects represent the millions of unseen and uncelebrated workers, often suppressed in the media and thus often hidden from our collective consciousness.

“The museum director saw [Gomez’s] artwork, and that prompted her to think about invisible labor and how there could be an exhibition that completely highlights and amplifies that,” Kienberger said.

The figures in Gomez’s paintings are faceless, perhaps symbolic of invisibility and unrecognized laborers who work in underpaid or socially unrespectable jobs.

The works displayed in Labor of Love emphasize a particular human factor: personal and intimate connections between labor and family, labor and community and labor and culture.

“A lot of the artists are speaking from specific experiences with family members who performed labor that perhaps went unseen or unnoticed or undervalued,” said Candice Bancheri, the Luce Foundation Curator of Academic Programs at JSMA at PSU.

“What’s really great about this show is that the curator really took all these angles of looking at labor in different ways, but the throughline with all of these works is that they’re very human centered,” Bancheri said.

This sentiment is evident in the work of Charlene Liu, a multidisciplinary artist and Professor of Art and Printmaking at the University of Oregon. On display in Labor of Love is Liu’s piece, “China Palace,” a multi-media homage to Liu’s family and their family-run restaurant. Using prints, cardboard, paper, ink and paint, Liu included photos of her mother working in the kitchen, old family photos and segments of the restaurant’s menu.

This piece speaks particularly to the emotional labor involved in the family unit, how labor brings family members together in a sense of purpose and pride, working towards a common goal—a joint effort.

In the service industry, these types of nurturing and generational practices often go ignored. “Sometimes we only see the byproduct of that work, and [here] we’re reminded of who exactly is performing that work,” said Bancheri.

“You could just tell [Liu’s mother] put her heart and soul into this restaurant,” said Bancheri, who met Liu’s mother. “Her passion for her work was not just representative of how her business could thrive, but how her family would thrive in a new environment.”

While Labor of Love contains representations, stories and perspectives of many different artists and life experiences, the individual elements of each piece are all interconnected. Regardless of the medium they use, each artist’s work tells a story contributing to the show’s overarching theme.

These stories highlight what we don’t see, are unable to see or refuse to see. This includes class inequality, systematic racism, the exploitation of marginalized people and the immigrant experience in a post-capitalist United States.

Near the museum entrance, there is also an interactive element of the exhibition. There is a small table set-up with bright pink note cards and pens, inviting visitors to contribute to a wall of notes hung with written examples of labor they’ve seen go unrecognized or underappreciated.

Visitors themselves—PSU faculty, students and their family members, essential workers and service workers—have shared stories of unrecognized or undervalued labor, a collective yet personal acknowledgment of what Labor of Love aims to promote.

“When I work with students I ask them, ‘Do you consider your work as a student [to be] labor?” Bancheri said. “Most of them say yes. They work very hard at their studies… Then my next question is, ‘Do you get paid to be a student?’ ‘No. ‘‘Are you paying someone else to be a student?’ ‘Yeah.’ So we see our definitions of labor—how we value that work, and how we determine what labor is worthy of recognition, fair compensation, safe working conditions and other basic legal protections—really has a huge impact on how we not only see ourselves, but how we see others.”

Many sectors of labor—critical to the functioning of society, cities like Portland and institutions like PSU—continue to be exploited and underappreciated, even deemed irrelevant or frowned upon. Labor of Love serves as a reminder to acknowledge these harmful views on stigmatized workforces, acknowledging the privileges abused and inequalities suffered throughout the labor market.

“All art has the potential to inspire change, but what’s unique about this exhibition is that it’s dealing with a topic that is pertinent to [most of] us—how it impacts our sense of self, how we value the work we do, the work our parents do…” Bancheri said.

These ideas and discourses are often overlooked. With assignments, relationships and other personal obligations taking up the vast majority of student’s time and attention, exhibitions such as these remind the PSU community that sharing and discussing stories of hidden labor is, in itself, an act of empathy and love.

Labor of Love is free and open to the public through Apr. 26. Among other programming events detailed on JSMA at PSU’s website, a panel discussion involving the artists and curator of the exhibition, Alexander Terry, will take place on Mar. 7.