What, exactly, does Portland State’s student government do?

The Associated Students of Portland State University (ASPSU) is not the most visible presence in students’ lives. At times, it can be unclear what purpose they actually serve. That’s for one simple reason: they hold no real power.

While the word government might typically imply some degree of substantive authority, ASPSU’s case implies anything but. According to their official mission statement, the student government’s role is—among other things—to “facilitate formal means of communication and interaction among students, student organizations, faculty, and University administration,” as well as to “advocate for and represent the interests of students before internal and external bodies.”

Those are certainly good things, and it’s hard to criticize ASPSU for trying to advocate for students. However, the fact remains that these actions are ultimately purely symbolic.

Consider the official job descriptions of key ASPSU positions, like president, the responsibilities of which include “creat[ing] the goals that the entire ASPSU student government shall act upon and support” and “provid[ing] a process for students to participate fully in the allocation of student fees.” It’s here that we have to ask: what do these substantively accomplish?

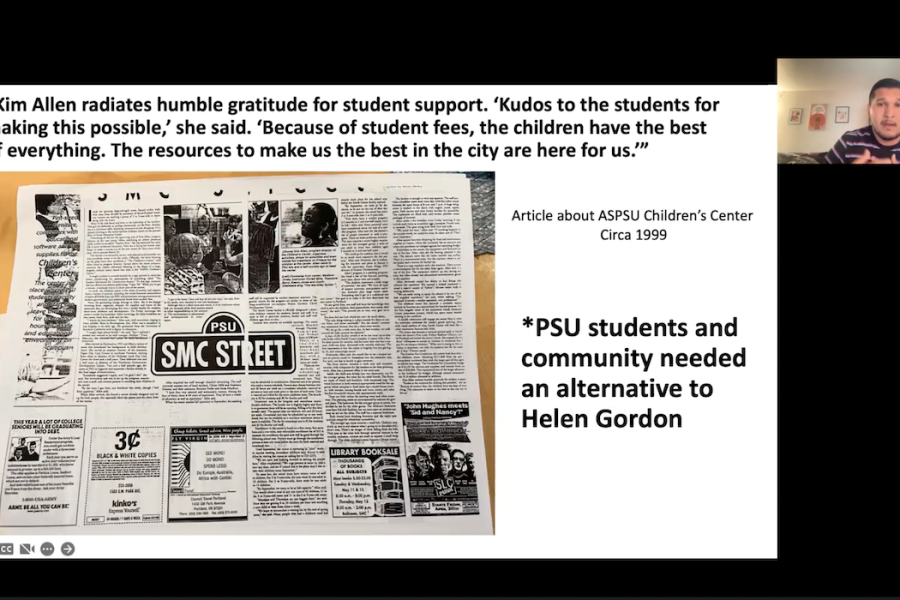

Take student fees, for example. The Student Fee Committee (SFC) has the most clearly defined role out of any branch of student government and the most visible exercise of power—the SFC is “responsible for recommending the Student Incidental Fee and Student Building Fee allocations and amounts to ASPSU and the University President,” per their website.

The average student—myself included, until recently—might assume that the SFC sets the Student Incidental Fee and Student Building Fee rates, as well as the budget for Fee-Funded Areas like the PSU Food Pantry, 5th Avenue Cinema and the Littman + White Art Gallery.

They don’t actually set these, however—they simply recommend a course of action to the university president and the Board of Trustees, who then have final approval on any changes. Additionally, per the 2022–2023 SFC Guidelines, the university president can send back the Student Incidental Fee Recommendation with modifications that the SFC must reconcile. Essentially, this means that while the SFC is legally empowered to make a recommendation about budget priorities, the administration still holds the ultimate authority over the process. Theoretically, the university president and Board of Trustees could unilaterally reject an SFC budget and stonewall them until they got the outcome they wanted. Who holds the real power here?

And that’s only the SFC, a branch of student government which—to reiterate—has the most explicit authority over material student issues. In contrast, it’s difficult to tell what exactly the Student Senate is supposed to be doing. The description of the role of senator simply states that the function of the Senate is to “facilitate formal communication between students, student organizations, faculty and PSU administration,” and that senators “advocate and represent the interests of the student body at large.”

These are noble goals, but they certainly don’t constitute a government by any meaningful definition. Let’s call ASPSU what it really is: an advocacy organization. And to be sure, advocacy groups are useful and necessary arms of the body politic, but let’s not confuse them with the groups that hold actual control over the levers of power.

This month’s ASPSU election debates for Senate, SFC and president/vice president typify the dysfunction inherent in the structure of student government. While the candidates gave many thoughtful, reflective answers to moderator questions, they were unfortunately hampered by the fact that—for most issues facing PSU students—student government is powerless to act.

In the president/vice president debate, one key question was the issue of PSU Campus Safety (CPSO) rearming their officers and especially the controversial decision to do so without informing students beforehand or gathering public input. Presidential candidate Lanie Sticka—current chair of the SFC, and someone with a wealth of experience in student government—had some difficulty addressing the topic.

“I think Portland State likes to lead by a form of shared governance, and maybe that isn’t exactly what happened in this case, communication-wise,” Sticka said onstage. Citing Portland State Vanguard coverage, Sticka noted that every student polled by Vanguard stated they disagreed with the decision. “That says something about whether or not the administration is necessarily listening to our students, so maybe that’s something we need to identify and definitely need to create some type of initiative towards, so… better communication with our administration is definitely needed, at least within this topic.”

That’s not much of an answer, but it’s worth noting that none of the candidates gave a convincing response. This isn’t to single out Sticka, but rather to remark on the fact that even the most experienced candidate onstage couldn’t give much more than a nod toward better communication and a seat at the table with the administration, because they can’t do anything else.

ASPSU senators and the president and vice president are less like actual senators and more like symbolic non-voting representatives. The closest analogue would be someone like Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, the District of Columbia’s representative in Congress. While Congresswoman Norton serves on two committees, is able to speak on the floor of the House of Representatives and otherwise has a seat at the table, she is unable to vote on any binding resolutions, and represents a district that is unable to even set its own budget without approval from Congress.

There is one thing that Norton has over ASPSU, though, and that’s her consistent advocacy for D.C. statehood. She points out that “D.C. residents can’t vote on any of the federal laws that govern them,” and that “Congress controls D.C. local laws and budget,” an undemocratic state of affairs that deprives D.C. residents of agency and their right to self-government.

Now replace “D.C” with “PSU students” and “Congress” with “the PSU administration” and hopefully you’ll see what I’m getting at here.

If members of ASPSU want to be a truly representative body for students, there’s one thing they should be fighting for above all else, and that’s real power. Why do we exalt democracy and self-government in the political sphere, but accept an undemocratic administrative autocracy at our university? Is that really all we deserve—a group of students play-acting democratic processes with no authority to carry out any changes that students actually want?

If that sounds radical, consider the contradiction between our society’s professed commitment to democracy and our actual denial of responsibility from the governed. Students—along with faculty and other community members—are what make up PSU. We deserve to have a real say in how our university is run, not to beg for scraps from an administration that has no obligation to listen to us at all.