In the early dusk of Nov. 20 a large stream of water arched over a heavily fortified barrier and began to soak the people assembled on the other side. The action was undertaken by security forces in service of the companies building the contentious Dakota Access Pipeline, and it was done so on purpose. It was done in spite of the freezing cold and the unarmed nature of the people who call themselves water protectors.

This scene has played out for months, ever since members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe established the first camp on April 1 of this year. The first water protectors, led by LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, made camp in the path of the project in order to draw attention to the environmental risks and the treaty violations related to the project that undermine the Standing Rock Sioux tribe’s status as a sovereign nation. In the months since then there have been thousands of water protectors in residence at several camps near the place where the Dakota Access Pipeline is set to cross under the Missouri River at Lake Oahe.

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe contends that the pipeline violates the 1851 and 1868 treaties that established the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, but the builders of the Dakota Access Pipeline insist they have the required permits and are currently continuing work in line with the expectation that they have every right to do so. As recently as Nov. 22 Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the pipeline, filed an application for a second pipeline to connect the Epping Transmission Company site with the gathering facility.

Condemnation Widespread, but Politics Muddies the Water

Condemnation of the Dakota Access Pipeline construction has been widespread. Messages in support of the water protectors have come in from across the globe, including attention from the United Nations and expressions of solidarity from places as far away as Mongolia. Stateside, politicians like Senator Bernie Sanders have been vocal since the early days of the protest, but others have been more cautious. As a candidate for president, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton offered support to water protectors, but nonetheless called for “all voices…all views” to be considered, including those of the pipeline builders.

President Obama has been less cautious and has also urged both sides to be considered. In a statement released on Nov. 2, President Obama stated that he would like “to let it play out for several more weeks and determine whether or not this can be resolved in a way that I think is properly attentive to the traditions of [indigenous peoples],” but has yet to use legal force to protect water protectors or enforce treaty rights.

Portland State at Standing Rock

Portland State students have been water protectors since the early days of the protest, and several are still holding space and providing transportation for supplies to the camps. Monty Herron, of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, Umpqua, Chinook, and Rogue River/Takelma, an adjunct professor with the School of Gender, Race and Nations and Indigenous Nations Studies says that, through prayer, it was determined that the best way to help was to “[answer the] Creator’s call to assist the Oceti Sakowin Nations in their call for help.”

Theresa Smith is in the American Indian Teacher Preparation program at PSU and a member of the Confederate Tribes of Siletz.

Smith is a student teacher at Metropolitan Learning Center in Portland. She and other teachers at the school are using Standing Rock as a way to show students a good and proactive model of protesting. “We talk about the whole non-violence stance of Standing Rock, and how the chairman of Standing Rock has called for nonviolence and protection of the waters,” Smith said.

Smith said that she puts focus on the different things that are being protected at Standing Rock.

After President-elect Donald Trump won the electoral college and lost the popular vote, people in Portland took to the streets and protested as they are still doing today. Smith said the noises she heard during those first days almost reminded her of a war zone. “Hearing those helicopters, the shots and not knowing what’s going on, Portland got a little taste of Standing Rock and what it’s been like there for months,” she said.

Smith said that her heart is at Standing Rock, and that it’s very hard to concentrate in school.

“It is my obligation to stay connected to what my friends and family are doing there, like how they are,” Smith said. “They are in jail. There have been shots fired, and we are all scared that someone is going to die there.”

Smith wishes she could go there, but with school and her family, she’s not able to make the trip at this time. “My mind is there, constantly, my heart is there as well,” she said.

Smith stressed that what the Natives are doing now at Standing Rock is not just for them, that it’s for the seventh generation. “If we allow the pipeline to go under the river and it doesn’t burst in our lifetime or in our children’s lifetime, it will burst eventually,” Smith said.

“We just want to be the people that they know fought for them,” Smith said. “We have this clean water because of their fight, if we don’t fight and it bursts, it’s their mess to clean up. We think ahead.”

Professors at PSU are using Standing Rock Curriculum to help aid classroom discussions and learning. One curriculum, titled NYC STANDS WITH STANDING ROCK, lists the timeline of United States settler colonialism and Oceti Sakowin Oyate Territory and Treaty Boundaries 1851–present as things people will find within the content. Key terms listed in the curriculum are things like capitalism, dispossession, Doctrine of Discovery, environmental racism, gender violence and Indian Wars.

Judy BlueHorse Skelton, of the Nez Perce/Cherokee nations, is a senior instructor II in the college of Indigenous Nations Studies at PSU and teaches classes like Intro to Native American Studies, Environmental Sustainability—Indigenous Practices, and Indigenous Women Leaders. Skelton said her syllabus, especially this term, recognizes that there’s no shortage of contemporary issues in “Indian Country” to examine and learn from.

“We can look at Malheur, which makes strong examples and are central to the basic themes in the courses that I am teaching,” Skelton said. “My syllabus design is very fluid and includes events that are hosted around Portland, along with current events.”

Skelton and other professors at PSU are thinking of ideas to give students credit for taking a trip to Standing Rock in the terms ahead.

Events have been held throughout campus. Last week, Indigenous Nations Studies program hosted a Standing Rock Teach-In for students and faculty members.

The United Indigenous Students in Higher Education student organization at PSU has also been working hard with the water protectors, assisting in supply drives and working to draft statements in support of the water protectors and against the Dakota Access Pipeline. UISHE’s most recent delivery of supplies went out on Nov. 16 and arrived on Nov. 18.

Herron calls the experience at Standing Rock a “game-changer, once-in-a-lifetime experience” that changes the way he views the issues facing First Nations, including “[the] de rigeur violation of treaties, and complete lack of cooperation with local and federal governments.”

Beyond Standing Rock

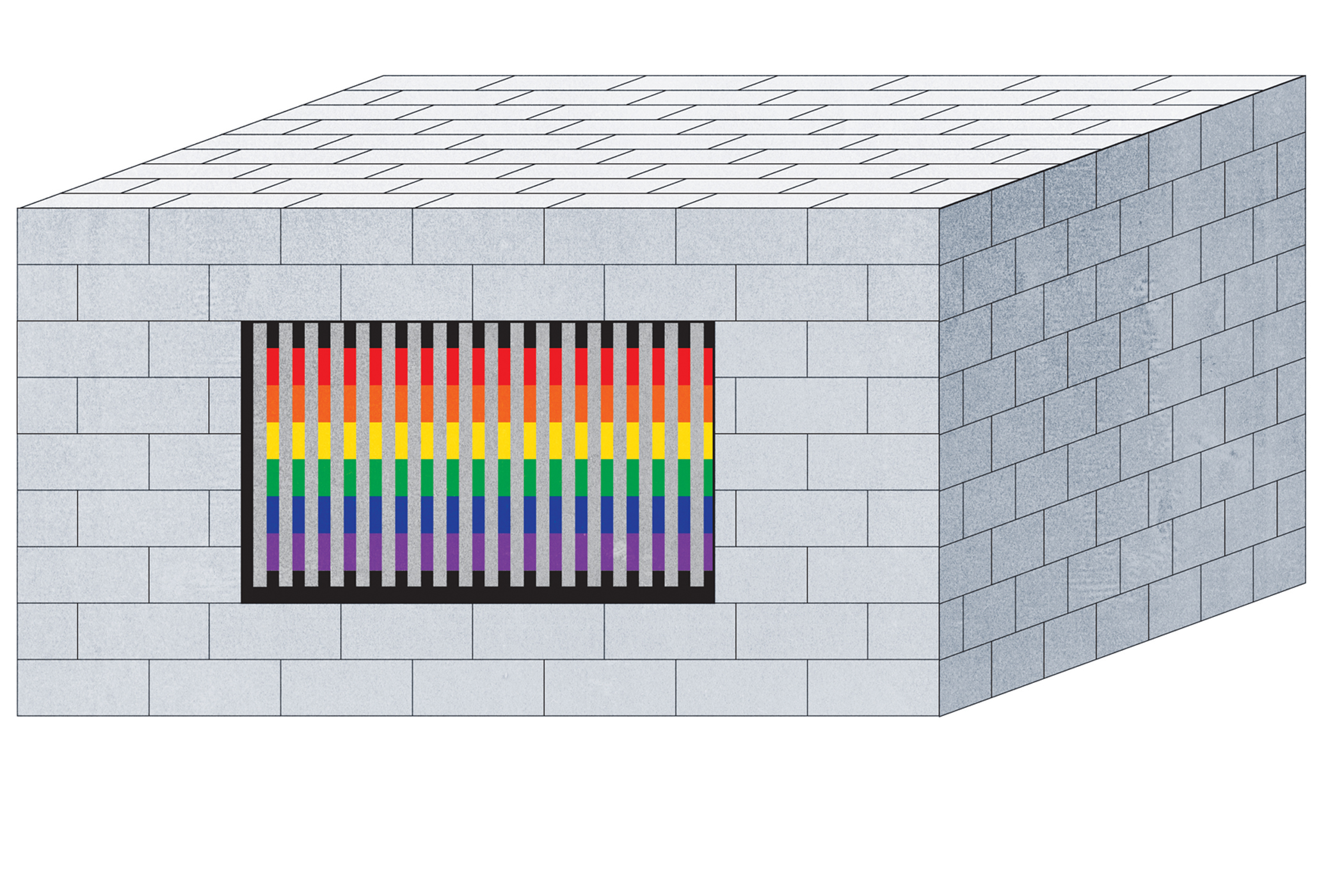

The current standoff at Standing Rock is not the only contemporary issue of indigenous resistance to environmental degradation and abrogation of treaty rights. In the Pacific Northwest a steady stream of protests by tribes has been prompted by numerous issues related to extractive industries. In the north end of the Salish Sea, which contains the Puget Sound, the Lummi Tribe has been fighting against a fossil fuel terminal for years. Closer to Portland, the Puyallup are now raising the alarm on a proposed liquefied natural gas terminal. In places like the Columbia River Gorge there have been frequent protests against coal and oil transport by rail, especially after a recent explosion rocked Mosier, Oregon.

Because water does not obey borders the issue has become international. Most famously this was seen in the Keystone XL pipeline fight, a situation that increased international tensions between the United States and Canada that persisted into the new administration of Justin Trudeau. Additionally, Prime Minister Trudeau has signaled that he will continue to work on new pipeline and extraction permits, in spite of calls by indigenous peoples to resist efforts to build them.

Nevertheless, the water protectors press on, and they bring their message to PSU.

“It has been my honor to be invited to speak to various student and community groups to give a first-hand account of what is happening in Standing Rock, and why it is happening,” Herron said. “Native people are mobilizing everywhere to say it’s not OK anymore. We will self-determine our future; we are taking back our narrative as a people.”

After 250 days, the water protectors are still facing down fire hoses, dogs, nonlethal rounds and temperatures plunging into the low 20s, but they have not signaled any willingness to end their defense of Standing Rock lands and the Missouri River, nor have they ceded an inch in negotiations, even in the face of an Army Corps of Engineers demand that they leave by Dec. 5. With support pouring in from across the globe, it does not look like they will stop.

To the water protectors the phrase, “mni wiconi”—water is life—is one worth fighting for.

In the next installment of this series we will look at the international implications of this fight and other environmental struggles by indigenous peoples worldwide.