Director Dennis Villeneuve’s 2017 film, Blade Runner: 2049, is the caliber of movie that must be viewed in an optimum-calibrated theater. Seeing it at Parkway North in January wasn’t the best viewing experience in cinema history, but the showing and popcorn were free, after all.

2049’s visual and sonic textures marries art criticism, avant garde tonal theory, and technological marvels into industrial budgets with a traditional Hollywood story structure. 2049 is a blockbuster that stands up to academic criticism.

Race & Culture

Villeneuve perfectly captures the gritty, distant yet all-too-familiar futurescape of Ridley Scott’s original Blade Runner. The character K (Ryan Gosling) drives a flying car sleeker than the 1982 model but passes by the same iconic billboards entreating Angeleans to fly Pan Am, play Atari, listen with Sony and “Enjoy Coca Cola.” Devoted Blade Runner fans recognize these as the same brands originally featured by Scott. 2049’s vision of Greater L.A. continues the theme of techno-orientalism, featuring the same Asian iconography found in the first film.

The original Blade Runner imagined Los Angeles in the year 2019 but made it more foreign: a melting pot spilled over. America’s anxiety over the Pacific Rim fuses with ever-relevant Russian tensions, and these anxieties translate to the film 2049, in which towering holographic ballerinas advertise “Soviet Happy!” in a world where Cyrillic writing is visually prominent.

2049 is racially homogenized. While both replicants and humans are white, all Latinx people and influence has been erased, and despite consistent East Asian influences, there are no Asian people. The film’s three Black characters have fewer than 10 minutes of screentime between them, although together constitute three more characters of color than Blade Runner offered. 2049 explores these themes as the revolution gathers forces in the dark recesses of the city– waiting to be led by the child once smuggled through its own underground railway. As K’s boss Lt. Joshi (Robin Wright) says, “The world is built on a wall that separates kind. Tell either side there’s no wall, you’ve bought a way. Or a slaughter.”

Literary Visual Poetry

The post-traumatic Baseline Test’s arresting call-and-response poetry comes from Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel Pale Fire, which depicts a man seeking to derive meaning from a near-death vision of a tall white fountain. Pale Fire is K’s favorite book, although Joi (Ana de Armas), his digital girlfriend, can’t stand it.

When K encounters Deckard (Harrison Ford) in the ruins of a Las Vegas casino, Deckard announces his presence with a monologue from Moby Dick. When K recognizes the reference, Deckard grunts with approval: “He reads.”

Water is a recurring visual motif throughout 2049 and exists as a controlled aesthetic element of Wallace’s lair. While it rains almost every day and night in Greater L.A, the surrounding ocean—the cleanest natural water ever seen in a pollution-soiled dystopia—provides the chaos that gives K the upper hand over Luv (Sylvia Hoeks). K dies surrounded by equally pristine, peaceful snow as the film closes. I like to imagine how water could represent an organic, non-human intelligence that—despite its increasing rarity—is still a deadly, purifying force as violent as fire.

Poetry and literature act as a sort of Turing test for the audience. If artificial intelligence can efficiently interpret and communicate complex meaning while invoking the sensual pleasures of poetry, are they not human?

2049 serves as a poem about perception, connection, desire, what it means to be real and whether any of it matters. Poetry and literature interweave throughout the film. The characters speak in verse and riddle, most notably Niander Wallace (Jared Leto), who always speaks in chilling lyric. K’s genetics are a poem for Joi, expressed as nucleobases: “A and C and T and G. The poetry of you.”

Women in 2049

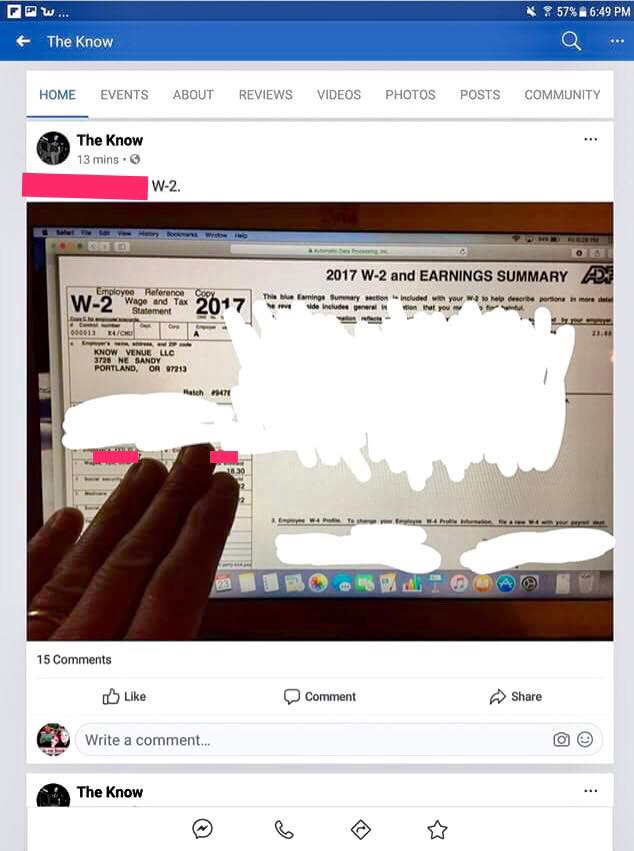

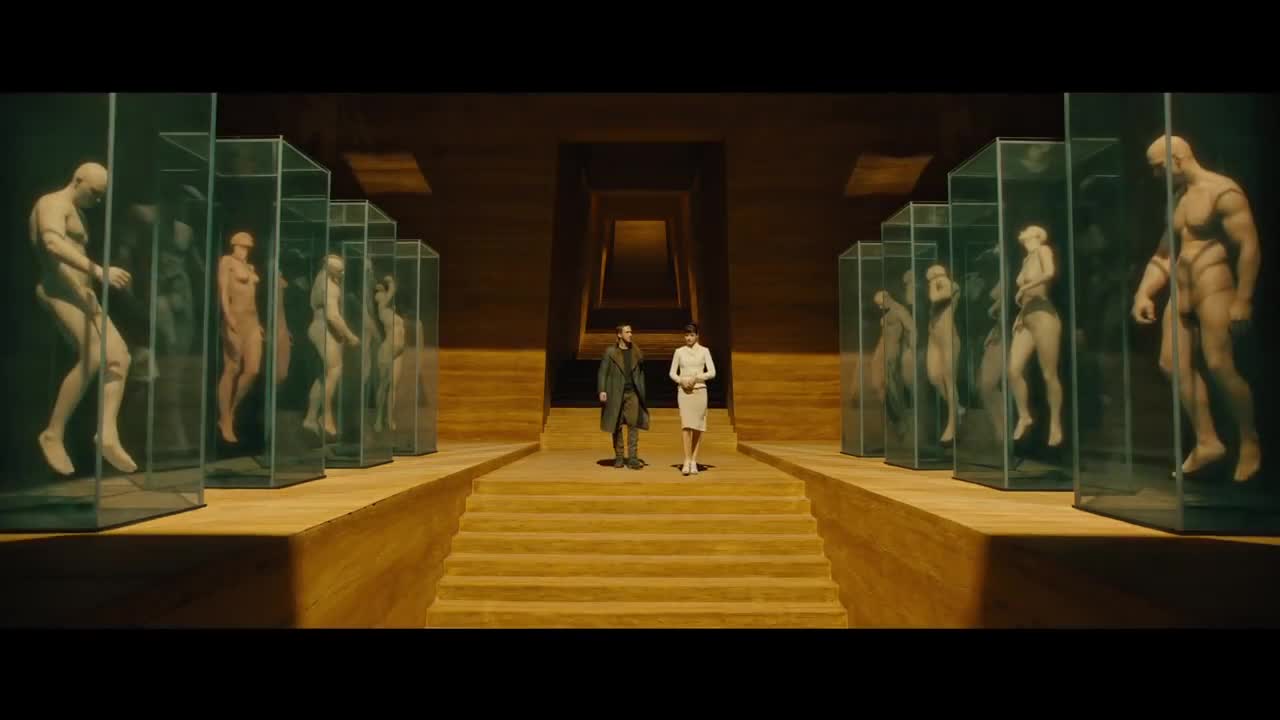

Wallace’s obsession with female biological reproduction reflects the values of numerous fertility cults. He and the fascist values he represents cannot see femininity beyond sexual processes and byproducts. 2049 is a dystopian future where women—digital, replicant and human—are reduced to their most base biological function: procreation.

Humanity colonized nine new worlds, cannibalizing Earth’s remaining scraps of natural resources as Wallace scrambles to recapture the feat of replicant reproduction. Wallace kills a newborn replicant (Sallie Harmsen) because she can’t breed. The killing is especially horrific from Luv’s perspective as she witnesses Wallace’s monologue and could have just as easily been Wallace’s victim, herself lacking reproductive functions,the antiquated benchmark for womanhood.

Greater L.A. is “haunted by the ghosts of digital women,” holographic ballerinas, billboard-sized nude digital women and colossal statues of naked women in high heels arching their backs in ecstasy dominate the skyline. While feminist critics slammed 2049 for its portrayal of women and the female body, 2049 posits a future belonging to women: The revolution will be headed by the one-eyed replicant rebel Freysa (Hiam Abbass) and centers around the miracle replicant-born child Dr. Ana Stelline (Carla Juri), a revelation that subverted our gendered expectations for the story.

But like every other cultural anxiety in 2049, female representation is crucial. Special effects aside, how different are 2049’s representations of women’s bodies from contemporary Western marketing, art or religion?

K’s hologram Joi embodies numerous archetypes of femininity at home, all antiquated in 2049’s universe, namely the June Cleaver housewife and the 1920s flapper dancer. Before her sex scene with K and Mariette (Mackenzie Davis), Joi even dons a traditional Chinese Cheongsam silk dress to embody the Western stereotype of the eagerly submissive, sexually available Asian woman.

Joi’s quest to define her reality and sense of realness makes room for the interruption of the oppressive binaries keeping 2049’s universe together—the wall which Lt. Joshi is so eager to maintain.

Homage as Deconstruction

While 2049 stands alone as a stunning neo-noir epic in its own right, Blade Runner fans are rewarded with homages to Scott’s original, such as Ford’s return and the holographic presence of Rachael (Sean Young), an angel born again. Deckard chases K into darkness under an arch with the word “homage” visible against blackness and gray dust. Deckard’s mustachioed former partner Eduardo Gaff (Edward James Olmos) also makes an appearance.

After a terse conversation with K, Gaff places a perfectly folded origami ram on the table. Or is it a sheep, a subtle homage to Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?—the basis for the original film? Each allusion to the past is another puzzle piece, but also another question, another layer of perception.

2049’s terrors are real. They loom over us like Greater L.A.’s rotting structures. The nightmarishly overpopulated ruins of an oppressive, corporate-dominated caste system found ethical arguments to make slave labor socially palatable. The orphanage-slash-sweatshop closely mirrors contemporary capitalist moral crises, like Apple’s use of child labor.

Audiences expecting traditional blockbuster narrative and visual form risk disappointment. But films like 2049 bridge the gap between action flick and arthouse by merging exciting risks with action, sexuality, and grandeur that blockbuster audiences expect. With 2049, Villeneuve asks us to suspend disbelief and find power in questioning what is reality, and who determines that reality for whom.

Blade Runner: 2049 is screening at OMSI through March.