Editor’s Note: After COVID-19 and all that has happened over the past few years, we have all experienced a collective trauma. The pain we have experienced as a collective community is high, yet with distance needed for so long, community gatherings took a back seat to safety, and many were left to suffer alone. Despite being and feeling alone, this trauma was a community trauma, one that demands a community response to healing. There are whispers throughout the artist community post-COVID—one thing I hear over and over is how creators want their art to reinvigorate community spaces, to allow viewers and creators to use these spaces to express their pain and experience collective healing. Renaissance of Community Arts is a new series that we will be running that focuses on spaces and events that encourage that sense of community and facilitate community healing.

The death of the American mall is hardly a recent phenomenon. Major retailers have been in steady decline since at least the early 2000s. The 2008 recession and COVID-19 pandemic have only exacerbated these trends. From Sears to Macy’s, Blockbuster, Sharper Image and Toys R Us, the 21st century has bankrupted and fossilized companies that had been wildly successful in the previous century. With the last American mall built in 2006, the age of e-commerce now utterly overshadows physical shopping centers.

This effect has given way to thousands of structural buildings suspended in a limbo of uncertainty. While many American malls sit abandoned, deteriorating skeletons of their former glory, others have simply mutated into ghosts of their capitalist past: Amazon warehouses, corporate offices or big-box monopolies. So we must ask ourselves—is this the best use of our own space here in Portland?

Even during the height of department store retail, malls were about much more than just shopping. Malls meant arcade gaming, bustling food courts and strolling the storefronts with friends. From Stranger Things to Fear Street and Wonder Woman 1984, it’s no coincidence that modern Hollywood aestheticizes the 1980s United States through the shopping mall scene.

We mourn the death of the American mall not because we seek elitist materialism in the form of big chain retailers. No, our nostalgia for such liminal spaces is really a reminiscence of their communal aspect. So why replace a faltering breed of consumerism with one infinitely more detached from its immediate community?

Some U.S. cities have already realized a greater alternative for their floundering shopping centers. In Providence, Rhode Island, the U.S.’ oldest mall Westminster Arcade, repurposed its vacant space as affordable housing units back in 2013. The former Landmark Mall in Alexandria, Virginia, became a temporary homeless shelter coordinated by the non-profit Carpenter’s Shelter in 2018 and is currently in the process of transforming into a site for Inovia Alexandria Hospital, as well as numerous housing units. What used to be Cinderella City Mall in Englewood, Colorado, has been transformed into a major community center, complete with a public library, civic center and outdoor art museum.

The American mall is not dying—it’s being reborn. At least potentially. The scope of such restructuring is dependent on the involvement of the community.

In our own backyard, the Lloyd Center yields massive potential for this kind of progress. The pandemic threatened the survival of the mall, and many Portlanders feared a total collapse. Nevertheless, the Lloyd Center persisted, and today we find the space transforming into a creative community hub.

At the forefront of Lloyd’s evolution is the indie clothing design company Dreem Street, Portland-born record shop Musique Plastique and locally shelved bookstore and publisher Floating World Comics. These businesses have all engaged with the broader community in their own ways, from hosting social functions to collaborating with radio stations and local musicians. Floating World Comics has organized art and animation festivals, galleries and signing events. The shop’s owner, Jason Leivian, imagines the future of the Lloyd Center in writing: “Is an empty mall post-apocalyptic or pre-utopian? We get a say in it. I envision empty storefronts filled with exciting local, independent businesses.”

The John Daniel Teply Gallery and Atelier is the newest Lloyd Center art district member, opening its doors in the mall only four weeks ago. The gallery’s premiering project is the 2023 International Art Festival, a multi-disciplinary experience celebrating ten countries over the span of four months. “We offer a way to connect culturally with the whole world,” said John Daniel Teply, the owner and curator of the gallery. “This week we had a cultural experience from India, next week we’re gonna have Palestine. The week after that, it’ll be Iran.”

The festival showcases song and dance, cooking demonstrations, lectures, storytelling, craft workshops and much more. “We’re working on trying to give a full experience of the countries that we’re working with,” Teply said. “The reason why we’re doing all these activities is to give an overlay of the culture of the artists.”

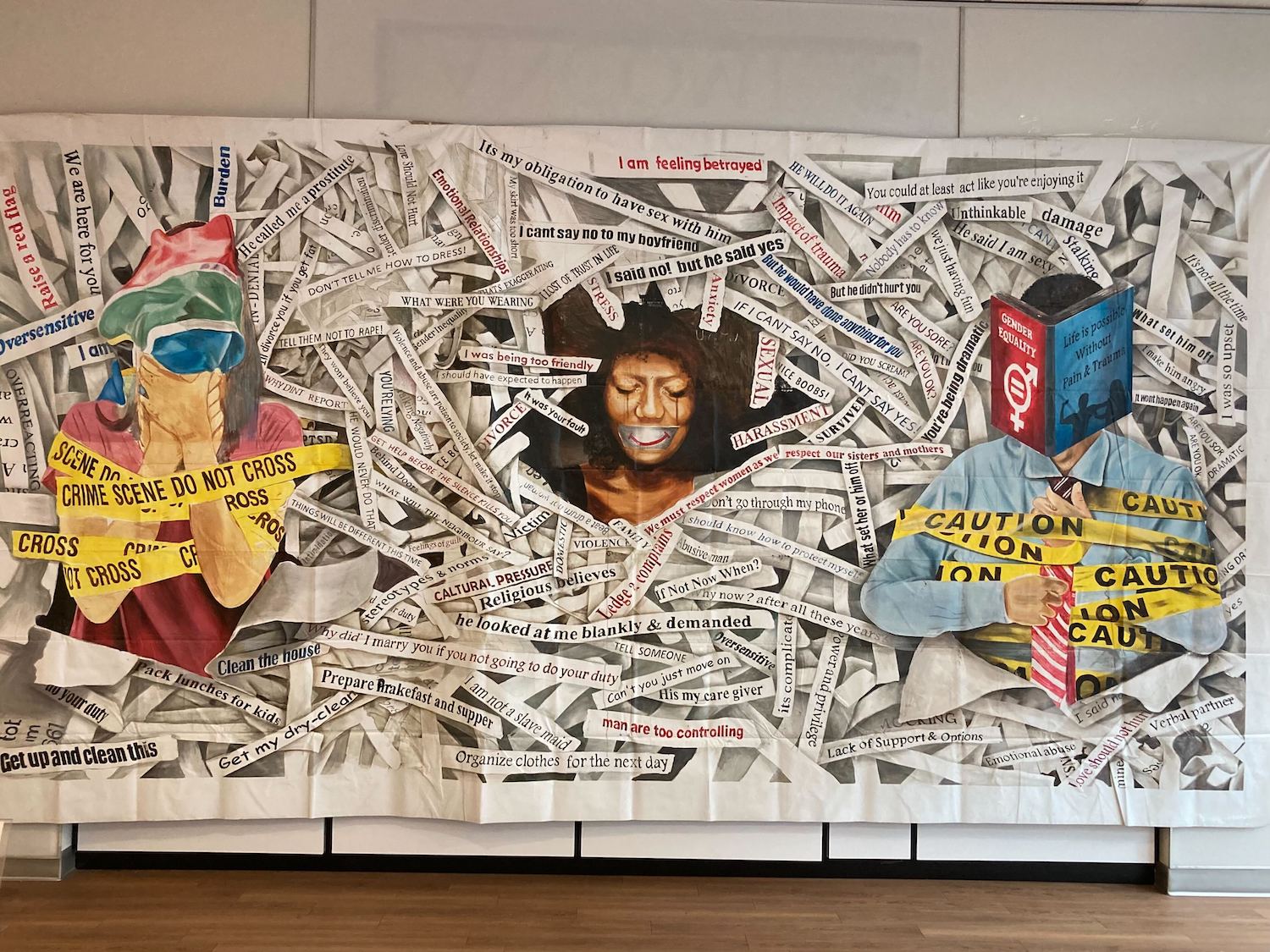

Alongside the festival events, within the gallery is displayed an alluring variety of large painted murals. This is the International Mural by Mail, a collaborative production in which “on one end, a mural is completed by the participating international artist. On the other end, another mural is completed by local Portland artists. The two murals are started in one location and then mailed back and forth to the other location, as the artists add to each other’s work.” Teply explained that this is “a chance to see something fresh. It’s about community and working with each other.”

A rich tapestry of history and representation, the gallery brings together a diverse panel of artists from within the community and abroad. Spectators can enjoy the visual art and participate in shared skills and histories from around the world.

Not only does the Lloyd Center benefit from the aesthetic and cultural atmosphere of the gallery, but the art mutually benefits from its location in the mall. Ultimately, a centralized shopping center allows for greater foot traffic and easier accessibility to places the general public may have otherwise missed out on. “What’s great about the Lloyd Center is that you have all different kinds of people that aren’t necessarily going there for an art experience, but because it’s in the mall and because there’s kind of a safe atmosphere about that, they’re willing to just walk in the door,” Teply said.

Teply mentioned that shopping malls such as the Lloyd Center are highly advantageous for creative galleries because they allow for sufficient physical space for people and exhibits, as well as ease of access in terms of parking and navigation.

With tenants such as these, the Lloyd Center is moving in a positive direction. As the U.S.’ old retail mall withers away, it’s up to each prospective community to decide how to repurpose their central spaces. The potential to fulfill Portland’s needs is significant, whether it be in affordable housing, health care providers or simply enjoyable spaces to learn and connect with each other. Our involvement with the pioneers of a new mallscape can maintain and grow the Lloyd Center into the thriving and equitable community center we want it to be.