Double talk.

Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler has claimed to be empathetic toward Black lives and the call for justice against police violence, but at the same time, he is urging Oregon’s Governor Kate Brown to respond with military force. Time and again, this approach has proven to be an escalation. It should stop.

Responding to prodding by the United States Attorney for Oregon Billy Williams, Wheeler has affirmatively acted upon the calls by U.S. President Donald Trump to “dominate” protesters. This kind of response is a violent, angry response to calls for a move toward more humane policing and genuine care and concern for Portland’s Black community.

Naturally, this kind of response has a history in the City of Portland.

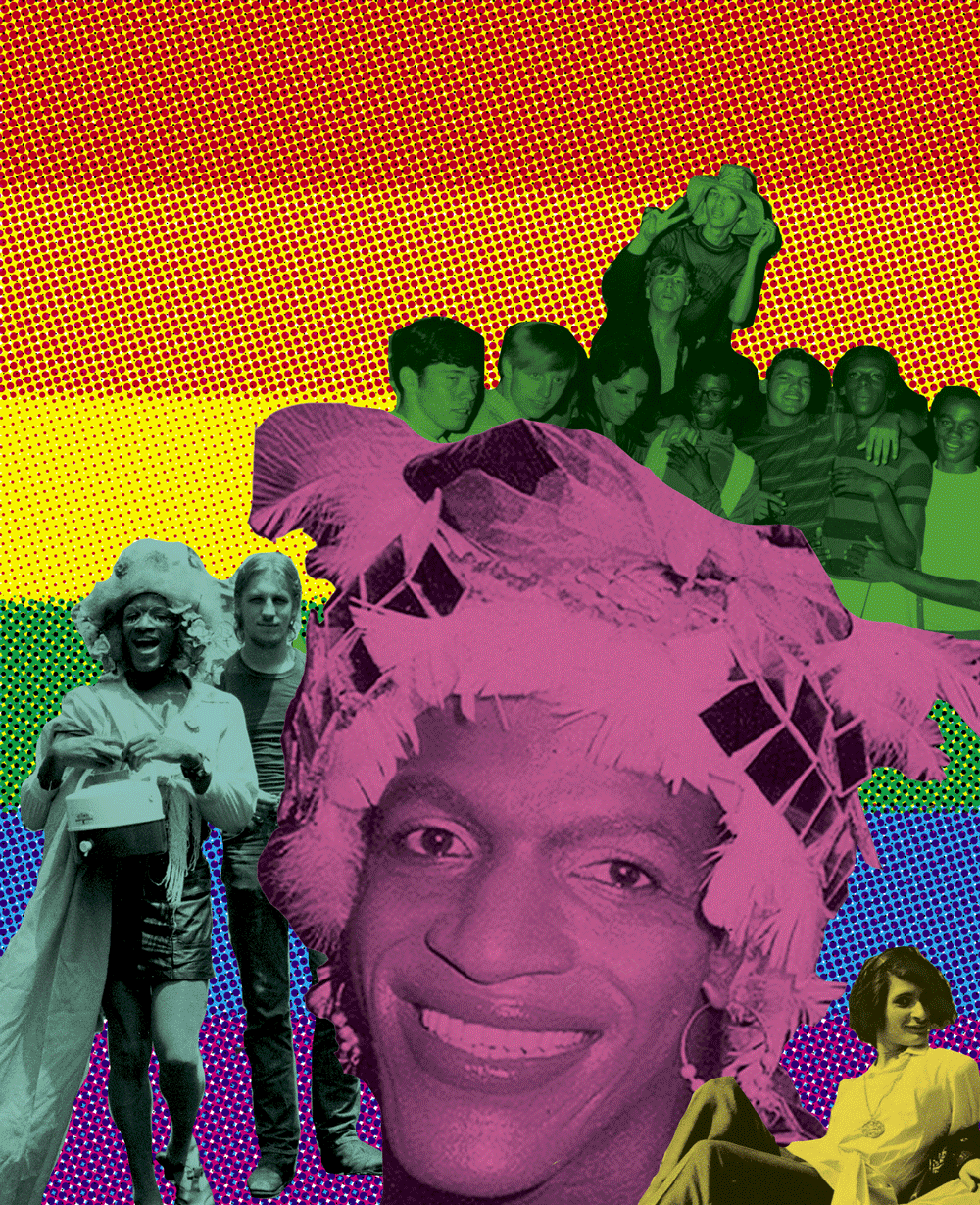

In a starkly similar time and place, Portland’s Albina community, the heart of Portland’s Black community, was racked with protests in 1967 at the same time other Black communities throughout the country were rising up. When police confronted a crowd of predominantly Black activists, the situation escalated into two nights of riots, largely prompted by police presence and rage at the effort to bring in state police and the National Guard.

The protests seemed to confirm in the mind of the Portland Development Commission and City Hall that it was time to move forward on plans to level much of the Rose Quarter and Albina, home to Portland’s Black community due to redlining. Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Interstate 5 and Emanuel Hospital dug in, destroying much of the community’s southern half and leaving parking lots and empty lots where homes and businesses once were.

The militarized response in Portland’s downtown will not serve to quiet unrest, it will only escalate things. In the end, televising images of a militarized city will not create a sense of peace, nor will it make the city feel safer. Instead, seeing that things are “so bad” that soldiers take up arms, citizens and visitors alike will have a different view of the city.

In response to unrest like Albina, the City Club commissioned a report in 1968 that was highly critical of flawed attempts by City Hall to bring genuine relations with the Black community. “Satisfactory police-citizen relations are not likely to be achieved as a reality in Portland,” the report states, “in the absence of a fundamental change in the philosophy of the officials who formulate policy for the police bureau.”

While it is true that there has been a change in this philosophy between then and now, it is clearly toward a far more aggressive and militarized response. Successive mayors since the 1960s have claimed to be working toward a peaceful, cooperative effort toward community relations but have spent more and more money on ensuring the police are an increasingly militarized force of stormtroopers.

Taxpayer money is spent on shields, pads, guards and weapons of endless sorts, all to ensure the response to any kind of social disorder, from failing to pay MAX fare to loud chanting, are faced with the business end of high-tech weaponry, ranging from “less lethal” rounds that can maim, to actual bullets. We’ve seen how this plays out all over the country. For example, in Louisville, where the exact kind of community liaison police and mayors claim to be seeking, David McAtee, a restaurateur and friendly neighbor, was shot and killed by the Louisville police. His body now, as of writing this, is still laying in the place he was shot. The response to civil unrest, then, seems to increasingly be “kill them all.”

It is natural to consider in this kind of situation whether this is a systemic or episodic problem with the police. Does it happen in rare instances of police overstep and in response to social disorder, or is it now the common protocol to simply shoot anyone who dares threaten a heavily-armed officer, even vaguely?

In Portland, the answer is the latter. Just last night, Gresham Police, acting as backup to the Portland Police Bureau, shot and killed a man.

All while the mayor decries injustice, his finger on the trigger.