Farmworkers are the backbone of society. They literally produce the means to our survival. Yet, despite their vital role, their work is undervalued and overlooked.

“27% of [Oregon] Farmworkers are in poverty,” stated a 2022 Oregon Human Development Corporation report. “They suffer rates much higher than the rest of Oregon’s population (13%).”

The total number of farmworkers in Oregon is more than 86,000 people, “12,000 of whom are not legally authorized to be here,” the report stated. “These undocumented Farmworkers are responsible for 18% ($732 million) of the state’s annual economic output and pay around $13 million in taxes annually.”

Farmworkers—undocumented farmworkers in particular—continue to face widespread social, economic and political marginalization on a systemic level. One significant issue which persists among migrant laborers is wage theft.

Alexis Guizar-Diaz—a sociology PhD candidate at Portland State—recently began working with the organization Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN), aka Northwest Tree-planters and Farmworkers United. Founded in 1985, the organization is dedicated to advocating for farm laborers in the northwest region of the United States.

Guizar-Diaz spoke of a recent experience with a candidate seeking endorsement from PCUN. Midway through the interview, the candidate broke down in tears.

“I [was] like, ‘Oh my gosh,’” Guizar-Diaz said. “I asked her ‘Que pasa? What’s going on?’ And she let us know that she hadn’t been paid in three weeks. Working Monday through Saturday, sunup to sundown in these tulip fields… all because the labor contractor said, ‘Hey, I can’t pay y’all. Maybe next week.’”

Jennifer Martinez-Medina—a public affairs and policy PhD candidate at PSU—grew up in a low-income agricultural community in Central Valley, Calif. “I like to say that it’s the world’s refrigerator because if you walk through any grocery store, most of the fruit you’ll see comes from somewhere in the Central Valley,” Martinez-Medina said. “Whether that’s Bakersfield, Fresno, Madera—any of those regions.”

Martinez-Medina described what it is like to drive through those regions, saying how you may pass by the dairy farms, and it may seem like nothing is there. In reality, thousands of farmworkers are working there.

“A lot of times, family farmworkers experience wage theft,” Martinez-Medina said. “They’re not able to use their family leave, and there’s really no recourse they receive, because we have a grievance-driven system, which requires farmworkers to come forward and express the issues that they’re experiencing. That puts them in a really vulnerable position, because the employer can retaliate.”

“A lot of our people aren’t viewed with dignity and are dehumanized, so it becomes very easy for people to take advantage of our community,” Guizar-Diaz said.

Farm work is inherently dangerous work. Laborers work with hazardous machinery and toxic chemicals. They risk exposure to infectious diseases and venomous animals. In addition, they work long hours performing strenuous work while exposed to the elements.

Guizar-Diaz detailed some of the most prominent hazards which farmworkers face today, ranking high among them being dangerous heat and air quality during the summer. Earlier this year, PCUN was able to secure strict rules regarding labor rights during times of high risk.

“It’s a basic right to have adequate breaks, water and protection against heat and smoke,” he said. “Every summer, we all face it, right? All the smoke? They’re out there picking fruit or tending crops. We literally have people dying out there, and it’s just insane.”

According to Guizar-Diaz, achieving even basic human rights for members of his community is often an uphill battle.

“I mean, there are the usual challenges of just how hazardous farm labor is—how repetitive the work is, how difficult it is on the body, how low-paying these jobs are,” Mendez-Medina said. “Even with some protections that we have now, they are still especially low-paying because of the seasonality.”

Many farmworkers in the U.S. still lack sufficient access to even the most basic necessities, such as clean water. While in his master’s program, Guizar-Diaz focused much of his research on this issue. Growing up around potato and wheat farms, he faced water shortages firsthand. He recounted times when he could not shower due to the neighboring farms depleting the local aquifer.

Martinez-Medina recalled a similarly bleak situation in her hometown, where the local water supply was tainted for decades with a—likely carcinogenic—chemical called 1,2,3-trichloropropane (1,2,3-TCP). Originally used as a pesticide, practical use of the substance was banned in the ‘90s due to the discovery of numerous health hazards to humans. According to Martinez-Medina, it was not until 2020 that her family was informed there were high levels of 1,2,3-TCP in their local water supply.

“In California, specifically, the state says that it’s a human right to have clean water, and they’re not fulfilling that right,” Martinez-Medina said.

Both Guizar-Diaz and Martinez-Medina pointed out that many of the laws which are put in place to protect laborers do not apply to workers who lack documentation—a fact which creates great disparities in the treatment of immigrant workers.

“The way I like to think about it is that all the issues that we face as a society are exacerbated for them,” Guizar-Diaz said. “You’re being paid poor wages and don’t have legal status in the United States… All the issues that we face as people as a society, just multiply that by 10, because you’re facing these barriers as a farmworker.”

Narsiso Martinez, a mixed-media artist from Oaxaca, Mexico, uses his personal experience as a farmworker to underpin the major themes of his art practice. “Some moments, like when I’m drawing, my mind just wanders,” he said, referencing his years working on farms in Washington. “It goes back to that situation I was in before.”

“I relive those moments, such as when I saw a person carrying a heavy bag only to trip with the whole thing… or an old lady who could barely carry the load she was carrying…” Martinez said. “Just really sad moments, they’ll be repeating in my head.”

Martinez pointed out how it’s often challenging for workers to speak about what they go through in their jobs as many of them lack official documentation, something he related to the broader theme of invisibility in the migrant workforce.

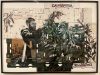

Martinez uses a unique practice of painting portraits on cardboard produce boxes rather than on canvas or paper. He portrays farmworkers and field laborers overlaid on the very packaging which serves to separate the consumer from the labor behind the product. This method ultimately calls attention to the subjects themselves.

A selection of Martinez’s works was on view at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA) at PSU as part of the gallery exhibition called Labor of Love. The exhibition aims to recognize and appreciate those who contribute to society through “invisible labor.”

“Hidden, unseen, or invisible labor is work that goes unnoticed, unacknowledged, and thus, unregulated, and that is too often unpaid or poorly paid,” stated the brochure at the entrance of the gallery. The show identifies marginalized identities across the U.S. as being the most vulnerable to contributing to these forms of labor.

“Sunday Morning” was one of Martinez’s works on view at JSMA at PSU. The piece repurposes a box which had originally carried asparagus from the company Altar Produce. Martinez reimagines the label to incorporate a religious framework, in which a worker veiled for protection from the harsh sun kneels in a swathe of land. In the distance, asparagus stocks frame a church building.

“We were talking about religion and how Sundays are reserved for God…” said Martinez about the painting. “I thought of how farmworkers are always working, including Sundays, no matter the season. Whether it’s strawberries, apples or cherries, they’re always in… They will not allow the workers to stay home with their families… That’s why I call it Sunday Morning. The church is in the background, and then there is the broken woman.”