TriMet is proposing an increase to daily ticket fares. Portland’s public transportation system has avoided increasing the bulk of the cost to ride since 2012, despite spiking inflation, fluctuating gas prices and tight budgets of the COVID-19 lockdown.

TriMet’s work also extends beyond transit routes. It engages in the community by contributing to affordable housing development, green technology initiatives and improving walkability of urban spaces, boosting equity intracity.

Yet the increase may place marginalized populations at a disadvantage.

In the proposal, prices would increase by between 15 cents and 60 cents depending on the type of ticket—with the exception of monthly and annual passes, which would not change. One general adult day pass would increase by 60 cents, from $5 to $5.60, and one honored citizen day pass would increase by 30 cents, from $2.50 to $2.80.

TriMet’s grounds for the proposal stem from the necessity for additional revenue to mitigate the system’s current financial deficit, which was caused by increasing inflation and decreased ridership as a consequence of COVID-19. The funds would be used to maintain transit operations, and to prevent otherwise inevitable layoffs.

The TriMet board of directors is scheduled to vote on the proposal in May 2023. If approved, the new prices would go into effect on Jan. 1, 2024. During the winter, they hosted open houses and opened up an online survey portal for community feedback about the proposal.

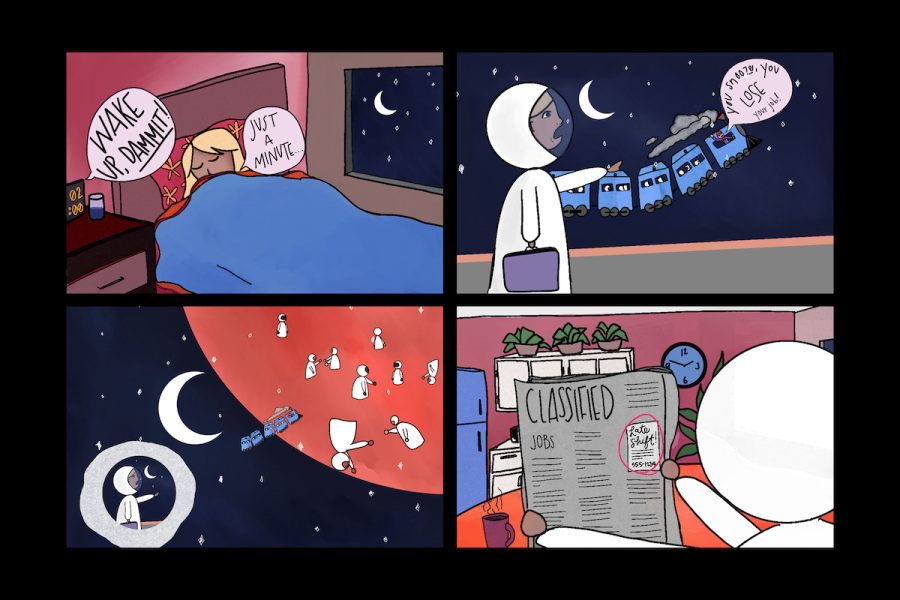

Specific demographics utilize United States public transit systems at disproportionately higher rates: those who are low-income, people of color and people under the age of 35, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Pew Research Center. Here in Portland, students make up a large portion of public transit commuters, with the most serviced transit stations concentrated near or on campus. According to a 2022 survey conducted by Portland State’s Transportation & Parking Services, 34.2% of students used TriMet to commute to campus.

Riley Woodruff, a junior computer science major, is one of these students.

“I use TriMet almost every day,” Woodruff said. “I think TriMet is an incredibly valuable resource and if it needs to have an increase in rates, then it should happen.”

Woodruff considered an alternative approach. “As someone who pays every time that I go, I think a better solution would be to probably crack down on people who aren’t paying,” they said. “I see a lot of people who don’t pay.”

Camron Baugh, a freshman environmental science major, agreed that the price increase may be a suboptimal but necessary reform.

“If it was a more drastic price increase, I would probably have a problem with it,” Baugh said. “But an extra 30 cents for a whole day, I don’t feel is too drastic for most people… I begrudgingly succumb to the way things are—our public services are severely underfunded and I’m fine paying the extra cents to keep those services running.”

Not all PSU students find the increases manageable, however. Samantha, a freshman biology major, said that for her and her family the increase would be noticeable.

“We are low income and we can’t really afford food half the time, so having to pay for transportation to get to school is already hard,” she said. “It’s pretty expensive just for every day, and to find more—even 60 cents—that kinda sucks.”

Many members of the community face financial barriers. PSU’s Transportation & Parking Services works to promote solutions to alleviate this burden for students. Firstly, all students enrolled in at least three credits can qualify for PSU’s Student Viking Pass, a discounted TriMet card that costs students $150 per term, as opposed to TriMet’s adult pass with a cost of $100 for one month. Secondly, any person whose income is less than $29,160 qualifies for TriMet’s reduced fare program, also called the Honored Citizen Fare. This pass costs $28 a month, and students can easily apply at the PSU Transportation office by showing proof of income.

While these programs do offer significantly discounted rates, Ian Stude—director of PSU Transportation & Parking Services—explained that it’s not a perfect system.

“I am concerned about the fact that the reduced fare programs require people to pay for their pass in advance,” he said. “I think a lot of folks who do pay casually for those services are really in that situation where ‘this [paying per ride] is the only way I can afford right now…’ I know folks who really can’t take that up-front cost on.”

The other issue is that many students and community members simply don’t know about these discounts.

“The folks who participate in those programs only make up a fraction of the number of commuter students who are eligible,” Stude said. Issues often arise due to inaccessibility of information, a frequent obstruction that tends to impact exactly those communities which need those services the most.

The fare increase comes with a potential detriment to the most vulnerable populations, and certainly a large group of citizens who earn above the designated income amount. Is there a better alternative?

“In the bigger scheme of things, in returning to normalcy the fare increase makes sense,” Stude said. “But it also makes sense that this is an opportune time to make a large change. I think it’s an important question to ask—is this the time to consider a fareless system?”

The logic that public transportation only functions when it’s paid for by individual riders falters quickly when examining agency budgets and outside transit systems. Corvallis is one pioneering example. In 2011, Corvallis saw a whopping 37.9% increase in ridership when the system became completely free to use. The city now funds the transit services by adding a small fee to the utility bill of residents, institutions and businesses. Fees range from two to four dollars per month for an average family. Many other cities have also found ways to make various systems of public transportation free: Provo, UT; Ellensburg, WA; and Boone, NC, to name a few.

“It’s a public service and I think it’s well known knowledge now that public services such as transportation should be free,” said Alejandro Segura, IT equipment and system specialist at PSU’s Transportation & Parking Services. Segura is also the president of PSU’s Service Employees International Union Local 89. Segura advocated for a restructuring of the system instead of a fare increase.

“[Free transportation] helps the folks on the lowest tier of the socio-economic ladder,” Segura said. “Why are we not working towards that? Why is TriMet not working towards lobbying for more money to make things free? How did we get into the opposite place, like ‘oh actually we’re gonna charge more money.’”

As a municipal corporation of the state of Oregon, TriMet’s budget is public information. Their 2023 expected financial requirements amount to $1.8 billion. Among other various sources of revenue, including a large, one-time influx from COVID-19 federal relief-aid funds, the agency’s budget outlines the following significant capital: $470 million from tax revenue, $164 million from federal grants, $32 million from state and local grants and $60 million from passenger fares. The 2024 fare increase is estimated to bring in an additional five to six million dollars per year.

As an institution, public transportation yields massive social benefits: it reduces urban sprawl, environmental degradation, pollution, road congestion and rates of vehicle accidents; is cost effective for commuters as well as urban development (lessens expenditures for road and parking facilities); generates more walkable cities and is an equitable resource for those who don’t or can’t drive. Why does government money continue to evade the infrastructures that would benefit us all, and instead compound as a burden borne by the least privileged?

Maja Birdwell, administrative coordinator at PSU’s Transportation & Parking Services provided an explanation.

“Really, the problem isn’t that they can’t pay their employees and offer low prices, the problem is that other departments are getting that money,” Birdwell said. “There is money in the community and in Portland, so why is it always transportation and community services that are the ones fighting for those resources?”

While TriMet has closed the survey and moved onto the next phase, its website encourages those who would still like to comment on the proposal to email [email protected], or sign up to speak at one of the public forums being held during board meetings on April 23 and May 24.

More information about the board meetings can be found online at https://trimet.org/meetings/board/index.htm.