Portland State campus housing is unlivable during the summer.

Portland State Vanguard wrote about this topic previously. Unfortunately, the issue has not improved. As average high temperatures hit 85.9°F in July, student housing remains as miserable as ever. It’s time for the university to make a change.

I want to share some of my own experience for context. I currently live in Blumel Residence Hall. Blumel is an old building—built between 1986–1988—designed to handle Oregon winters. Each unit has carpeted floors, thick cinder-block walls and small windows which only partially open at a sub-45° angle.

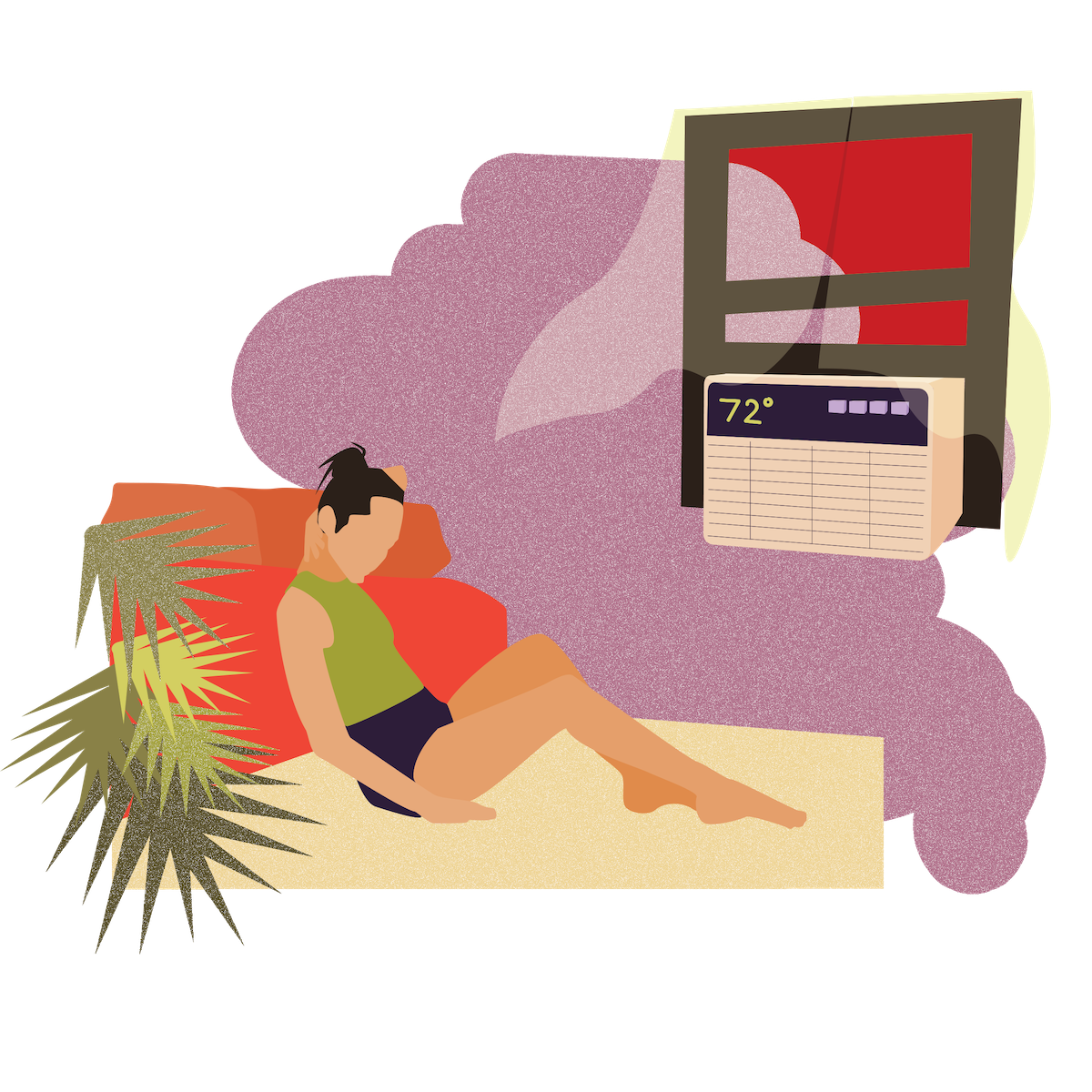

It’s pretty nice in the winter but hellish in the summer. There is currently an air conditioning unit running all hours of the day in Blumel’s lobby, and the room temperature stays around 78°F. In my room without air conditioning, it’s much worse. My bed registers at 81.3°F around 11 a.m. That’s after a relatively cool day and an entire night of blowing cold air in through the window. It’s much worse during the hours of peak heat.

At any given time, the temperature inside my unit is about 10°F hotter than it is outside. That’s practically uninhabitable. Blumel is so unbearably hot during the summer for multiple reasons—all of which compound on one another.

First is the windows. They open less than six inches—shorter than the length of my hand—and point downward instead of outward. These minuscule openings hardly allow any air to pass through, meaning air circulation is dramatically impaired—even with a powerful fan. It’s impossible to get the hot air out and the cold air in fast enough to keep up with the day’s heat.

Second is the carpets. Besides a few exceptions—such as the kitchenettes and bathrooms in each unit—nearly the entire building has carpeted floors. Carpet is a thermal insulator, meaning it stops heat from circulating around the space. Non-carpeted floors are typically better thermal conductors, allowing heat to easily transfer from the floor to the rest of the living space.

Third is that Blumel is in what’s called an urban heat island, similar to other PSU residence halls—such as Broadway, Ondine and Stephen Epler. This is where structures such as buildings, roads and asphalt lots absorb and reflect heat more than areas with tree cover. Urban heat islands usually have daytime temperatures 1–7°F higher than comparable areas with tree cover, and nighttime temperatures are about 2–5°F hotter.

These issues magnify each other, leading to a situation where outside temperatures are consistently hotter than average while inside temperatures remain high day and night. Similar to half the units in Blumel, my unit faces a large, unshaded, south- and east-facing parking lot which absorbs the worst of the heat during the day and continually reflects it back into the building.

Once that heat gets in, the inadequate window openings and insulated carpeted floors ensures the air inside remains hot and stagnant. Stagnant air is a significant health concern since it traps air pollution and can potentially cause respiratory distress and other health issues.

Additionally, high nighttime temperatures severely impair the body’s ability to sleep. According to a 2012 study, “heat exposure increases wakefulness and decreases slow wave sleep and rapid eye movement sleep,” which are essential for functioning in daily life. Losing the ability to fall into deep sleep and REM sleep affects every part of one’s body, from one’s circulatory system to the immune system to brain function and mental health, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

According to the National Weather Service, when Blumel finished construction in Aug. 1988, the average high temperature was 80.9°F. In Aug. 2022, the average high was 87.3°F. In the past few years, Portland experienced multiple hotter-than-average summers, such as the 2021 heat dome event when temperatures exceeded 100°F for three consecutive days.

It’s long-past time for the university to uphold its obligation to students’ physical and mental health, and do something—anything—about extreme heat in university housing.

Oregon Senate Bill 1536—also known as the Tenant Right to Cooling Bill—passed into law during the 2022 legislative session. It requires landlords to allow portable air conditioners and window-mounted air conditioning units under a list of conditions. For example, tenants cannot violate building codes when installing an air conditioning unit. Landlords can ban their use from October to April, however, they are not legally allowed to ban air conditioners altogether, as stated by the PSU 2022–2023 Housing Handbook.

It’s unclear what the timeline will look like for PSU to comply with the new state law. Regardless, there are many steps they could take right now to fulfill their duty to protect student health.

First, the university could replace the window joints in each unit to allow windows to open fully. In their current state, air circulation is middling at best. Simply opening the windows completely would do wonders for moving air—and therefore heat—in and out of units.

Second, they can and should remove the carpeting in each unit and common areas. Carpet may have made sense in the 1980s, but it’s inadequate for the current climate.

Third, the university can work with the city to plant more greenery around campus, expanding shaded areas. The Park Blocks are an excellent addition to downtown Portland. It’s clear when one compares the shady park to the unshaded areas surrounding it how much cooler it feels—even on the hottest days. While this would be a long-term project, the campus community would greatly benefit from getting a head-start on expanding green spaces now rather than later. I’ve written about the benefits of green spaces in urban areas, which are especially clear in the summer months.

Whatever happens, it’s untenable for the university to continue to do nothing. Students pay the same amount of money to live on-campus in the summer as they do any other term, and the university essentially abandoning us is shameful. It’s time for PSU to step up and carry out its responsibility to safeguard student health.