In a world where menstruation is often stigmatized, a groundbreaking shift is happening. Thanks to innovative research and technology, the once-dismissed menstrual blood is emerging as a source of valuable insight into the health of menstruators.

The things that come to mind when one considers getting tested for a disease are probably blood draws, urine tests and nasal swabs. Period blood doesn’t spring to mind even though two billion people worldwide menstruate.

The United States Food and Drug Administration approved a health test utilizing period blood for the first time earlier this year. The diabetes biomarker detection at-home test provides an alternative to the blood draws which are conventionally necessary for diagnosing the condition.

“One of the biggest hurdles in embracing period blood testing is overcoming deeply ingrained misconceptions,” said Søren Therkelsen, co-founder of Qvin. He emphasized the need to dismantle the stigma surrounding menstruation. He challenges the notion that menstrual blood is gross or unnatural, asserting that it holds valuable health information just like any other bodily fluid.

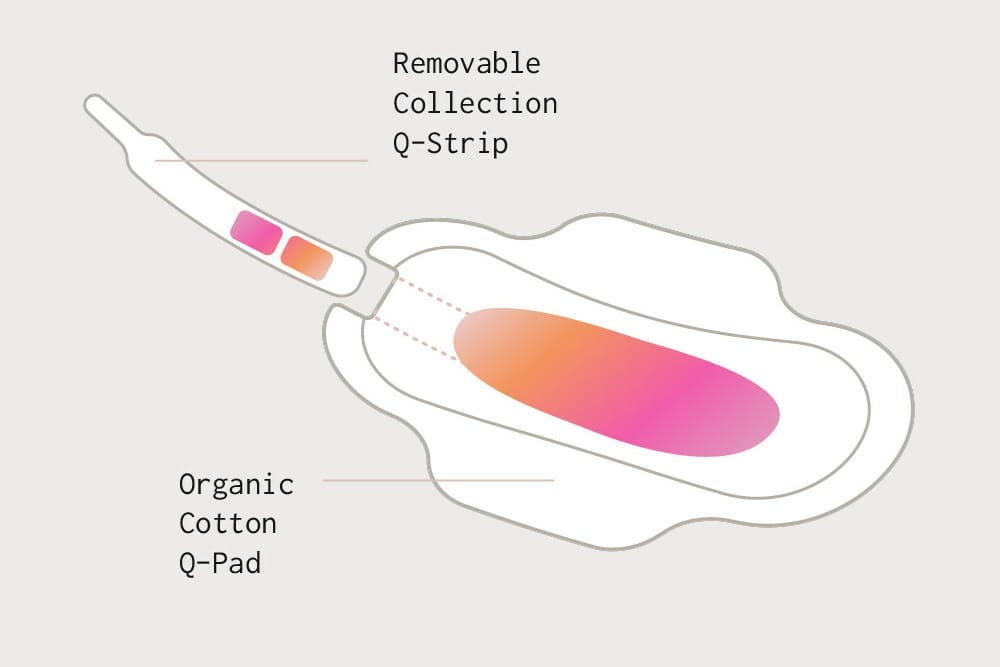

The Q-Pad test kit from Qvin has two special menstrual pads with removable collection strips. After being collected during one menstrual cycle, both strips are mailed to a certified laboratory for testing. Results arrive via app or email.

The Q-Pad measures the average blood sugar over three months by testing the A1c biomarker for people with diabetes.

“On average, a [person with periods] menstruates for about 40 years, which gives about 400 times where you can collect menstrual blood for health testing,” Therkelsen said.

Additionally, Therkelsen discussed the potential for detecting sexually transmitted diseases, offering a private and anonymous solution for young individuals.

Amy Whitbread—chief scientific officer at the company theblood in Germany—highlighted the transformative potential of menstrual blood analysis. Through their Cycle-Check kit, individuals gain unprecedented insights into their menstrual cycles, empowering them to better understand and manage their health.

The Cycle-Check looks at the physical characteristics of menstrual blood alongside information on the menstrual cycle and its symptoms. It then provides information on what these can all mean in terms of health and offers some knowledge on how to help manage symptoms.

Researchers are also developing and validating a menstrual blood test to analyze biomarker levels like C-reactive protein and reproductive hormones. This test will provide personalized health data and guide users towards optimized diet, exercise and lifestyle choices.

Beyond dispelling myths, testing period blood has tangible implications for early diagnosis and treatment. Whitbread highlights research showing unique proteins in menstrual blood that could unlock insights into reproductive disorders such as endometriosis and ovarian cancer.

“This is what we and other companies that are working with menstrual blood are trying to prove: that it is actually a beneficial biological fluid and like liquid gold,” Whitbread said. “It is basically an untapped resource. And it’s exciting, because we don’t know that much about it at all, and we are just at the first stages of learning about its potential, and it’s already proving to be something extraordinary.”

A study by Heyi Yang et al. showed that there are 385 proteins that are unique to menstrual blood. “These proteins are not found in a typical blood draw or vaginal fluid, and we have no idea what most of them do,” Whitbread said. “These could be the key to early diagnosis of certain reproductive disorders, like endometriosis and ovarian cancer, which usually requires a physical exam, MRI or an invasive procedure, like a biopsy or even surgery.”

Another study by Sara Naseri compared samples of menstrual blood with blood circulating through the body from 20 menstruators over two months. The team concluded that menstrual blood could reliably estimate levels of several biomarkers, including diabetes, inflammation and reproductive hormones, and could be an alternative source for diagnosis and health-monitoring.

In addition to testing menstrual blood for the diagnosis of diabetes, Naseri et al. have investigated the possibility of detecting human papillomavirus strains which significantly increase the risk of cervical cancer in the blood.

According to the World Health Organization, diabetes is responsible for over 100,000 fatalities in the U.S. and approximately 1.5 million worldwide annually. Diabetes-related complications encompass a range of adverse effects, such as those affecting the eyes, kidneys, nervous system and heart. Preventing these complications and ensuring timely treatment are all achievable by these tests.

Physicians have utilized blood tests to evaluate the health of their patients for nearly three-quarters of a century. Presently, the blood contains hundreds of biomarkers that provide insight into our health, ranging from nutrient deficiencies to cancer indicators.

Menstrual effluent—which consists of discarded cells and tissue from the thickened endometrial lining of the uterus during each cycle—is considerably more complex than arterial or venous blood. It contains blood obtained from other anatomical sites via blood draw, but it also contains uterine-specific proteins, hormones and bacteria.

For students intrigued by this burgeoning field, the opportunities are boundless. Whitbread encourages aspiring researchers to get involved, emphasizing the growing demand for expertise in menstrual health. With menstrual blood analysis poised to revolutionize healthcare, students can shape the future of menstrual health research.

It’s important to challenge old ideas and see the transformative potential of menstrual health research as we enter the unexplored frontier of period blood testing. Utilizing the potency of menstrual blood could completely change how we think about and meet health needs. Let’s use this time to give people more power, break down barriers and make the future healthier and more open to everyone.