The pope is dead, and the Catholic Church is left without her pontiff. As the pageantry and procession that follows a papal death is performed, the College of Cardinals is already preparing to elect a new Vicar of Christ.

Rather than recommend a film such as 2024’s “Conclave,” which seems timely enough, I want to offer a film that looks us squarely in the face regarding issues of faith and dogmatic fervor. This film is Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 silent film “The Passion of Joan of Arc.”

When rigor mortis sets in, the face deflates and distorts—the tension of life is no longer present. The world has looked upon death, setting her hands upon Pope Francis’ face. Yet what Dreyer caught on film 97 years ago is a necessary contrast that the contemporary era must see.

The film is based upon the actual record of the trial in which Joan of Arc faced charges of heresy by French clergymen sympathetic to the English. A large contention within the trial is her claim that God has guided her mission to drive the English from France. That, along with the “sin” of wearing men’s clothing, leads the church’s clergymen to ultimately condemn her to death.

The titular saint is played by Renée Jeanne Falconetti in her only film role. She proved she needed only one credit to burn her face into the collective imagination of cinema forever.

Dreyer creates a violent intimacy between the viewer and the characters through the use of closeups and uncomfortable angles. The judges and clerics doggedly questioning Joan are looming, high contrast presences. Because it is a silent film, the cuts to intertitles help the viewer make sense of what is being said. Yet words are not necessary in order to see what is occurring on film.

Falconetti gives a performance that transcends any period of cinema. It is transcendent in its nature due to the way she utilizes her facial features. Disconnected, glazed and tear-stained stares move the viewer to join her in her journey of spiritual rapture.

The concept of martyrdom is complex, yet Dreyer and Falconetti give this experience a haunting and visceral face. Falconetti simultaneously displays the dread and agony of thinking what will be done to her corporal form while also cultivating a performance that shows the glimmers of illogical, spiritual joy this brings her.

Hypocrisy has carved itself into the lines of the cleric’s faces. For Joan, there is simplicity and spiritual elegance signaled in the shadows of her countenance.

The clergymen infamously question if Joan knows she is in a state of grace. This theologically disingenuous and provocative inquiry is met with Joan responding with an answer of clarity.

“If I am, may God keep me there […] If I am not, may God bestow His grace upon me!”

Ultimately, Joan receives her martyrdom in a harrowing final scene. A crowd of spectators gathers around the stake as she assists the executioner in tying the ropes that bind her to death. As Dreyer angles the camera below Falconetti, her shaved head and meager figure are imposed in front of the stake where she will receive her martyrdom.

In her final moments, she clutches a processional cross. During the frantic scene that ensues, that same cross is held in front of her with the crucified Christ witnessing her gruesome death, silent and motionless.

One of the men in the crowd exclaimed, “You have burned a saint!”

Dreyer ends the film with a final shot of the stake being consumed by the flames, with a cross situated in the background. It serves as a visual representation of one woman’s faith transcending that of the institution supposedly safeguarding it.

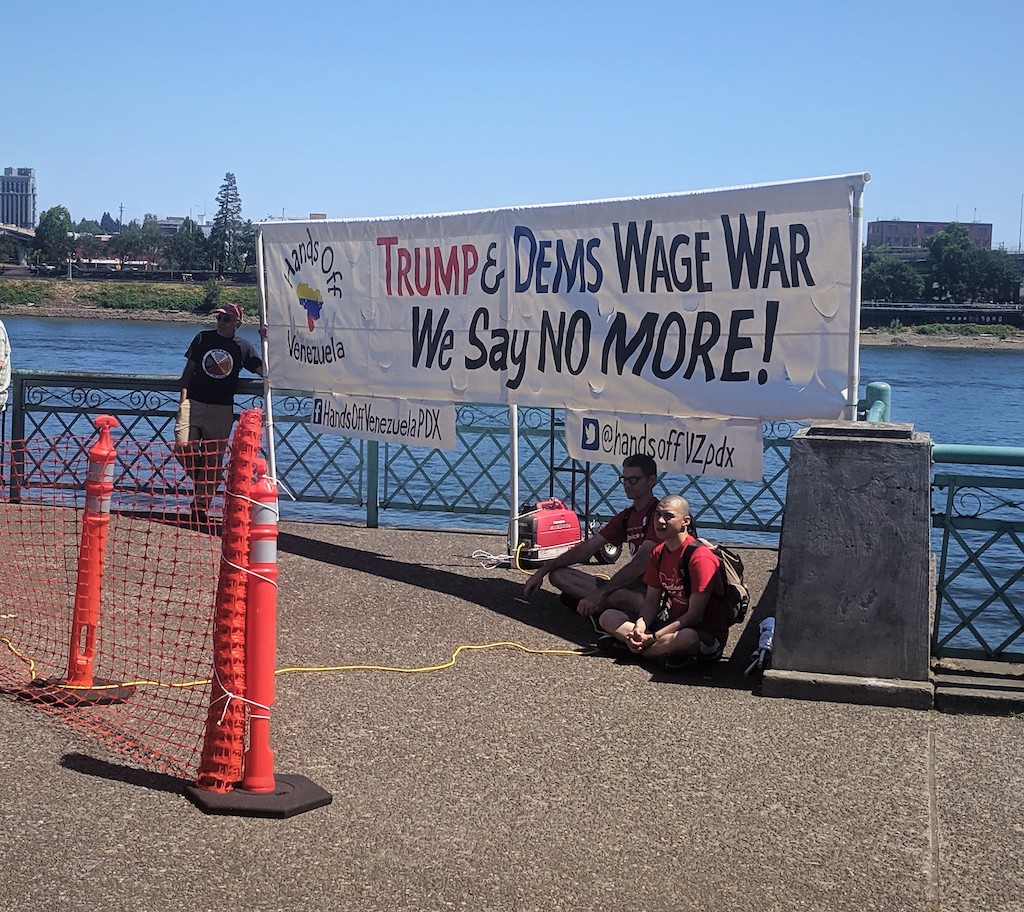

A film such as this seems so far removed from our contemporary world. Its black and white shots, religious subject matter and silent dialogue seem to constrain it to a bygone era of filmmaking. In this viewer’s experience, though, the film could not speak more loudly and clearly to our generation.

It serves as a reminder to me that the truth is hard to look at in the face. Dogmatic adherence to any ideology is comforting and blurs the visages of others outside our own sect. While I cannot relate to Joan’s thirst for martyrdom, I did see someone else who hoped for something more even in the most dire of circumstances.

This film is necessary as the world chaotically comes to terms with itself. The tension of life cannot leave our faces. Dreyer and Falconetti show us that we must continue to be animated by hope, even when the world burns its saints.