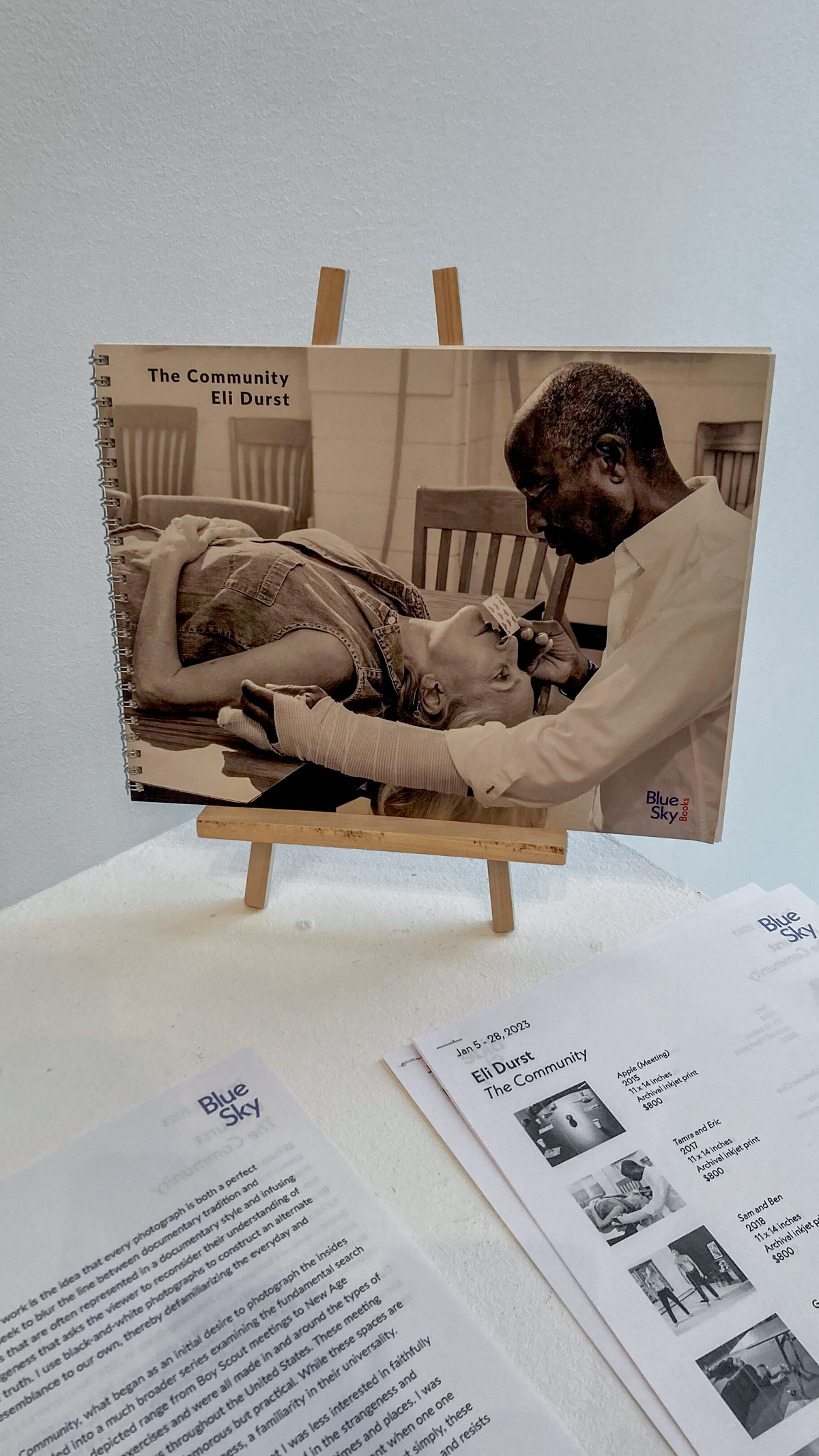

Throughout the past few years of pandemic isolation, the value of in-person community has become more apparent than ever. Eli Durst’s photography project, The Community, explores a variety of gatherings and settings where people come together and foster connection. Blue Sky Gallery, also known as Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts, will display the exhibit until Saturday, Jan. 28.

Durst’s current work originates from his undergraduate time at Wesleyan University, where he majored in American Studies and took his first photography classes. “My undergrad work focused on using the camera to look at the construction of that normative American identity,” Durst said. “Not that it actually exists, and of course, that’s the great thing about America, but of course we think it exists. It’s a politicized issue and is obviously extremely contested on who gets to be a normative American.”

After graduating from college, Durst moved to New York City, where he began his work at the printing lab Griffin Editions and assisted photographer Joel Meyerowitz. “Both were great real-world educations in photography, printing and the consumption of imagery,” Durst said.

Durst decided he wasn’t interested in a flat-out critique of suburbia. “Obviously, the deficiencies or issues of suburban America are well-trodden areas in the art world,” Durst said. “So I shifted my focus to, ‘Can I convince myself of poetry or meaning or value in these spaces? Can I find something meaningful or sensational in an extremely mundane space?’ Something that felt beautiful but kind of disposable in the way that so many things we consume in America are.”

After three years in New York, Durst knew he wanted to return to school. “For me, it was really important to go back and be part of an art school community,” he said. “That there were things that I needed to learn and know.” At Yale University, he continued his work as usual but received a lukewarm reception. “I think from the point of a grad school critique, it’s like, ‘If you are gonna work the same way you were before, do you need to be here?’” he said.

He switched from his comfort zone of 4:5 color photography to black and white digital and began experimenting with flash and strobe. These changes allowed Durst the freedom to expand his reach and get to the heart of what he was trying to say. “I started casting a much wider net,” he said. “You had to really know the people with 4:5 [film format], but with digital, you could shoot with whoever.” Durst captured various events, such as bingo halls, teen skating groups and male strippers. He started photographing everything he saw, not knowing or caring what it meant or if it would end up in his final portfolio.

Durst’s time shooting the project was full of one-of-a-kind experiences. He pointed out a shot of a well-dressed man in a Dunkin’ Donuts. “I really felt blessed by the photo gods with this one,” he said. “I was in grad school driving around Connecticut photographing and really just failing. Not getting anything good. There was this man in a suit seated in a sort of faux living room library inside the Dunkin’ Donuts. I loved the beauty of it. I had all my photo gear and was like, ‘Should I ask if I can photograph him?’ And was like, ‘No, I’m not going to bother him.’ So I went back to dejectedly eating my muffin and drinking my coffee when I felt a tap on my shoulder, and it was him. His name was Dr. Hans Gandhi, and he came up to me and said, ‘Will you take my photograph?’ It felt like I had earned it because I had failed so miserably… Sometimes in photography, it’s like, ‘Oh, you got lucky,’ but you make your own luck by taking pictures and failing, and shooting hours and getting nothing—like, you make your own luck.”

Eventually, Durst realized he needed to narrow the project’s scope. Around this time, he was going to boy scout meetings in a church annex’s basement, and fell in love with how the space felt. “I loved the architecture of it, the genericness, the specifics, the linoleum floor, how everyone knows that space, how familiar the space is in America,” Durst said. “I started thinking about what else could be happening in a church basement. That was my first real idea of what this project was going to be. That could be boy scout meetings, bible classes, new age spiritual groups, corporate team building exercises.”

“It expanded from a church basement to a community center-type space,” Durst said. “The idea for me was, at a certain point, can I create my own fictional community center? Can I make it feel like all these activities could be happening simultaneously in different rooms of the same building?” It was here where The Community was born.

The Community was photographed from 2015–2018, during which Durst traveled to various places across the country. Despite this, the sameness of the spaces he visited gave the work a unity that transcends specific space or time. “The places don’t really change,” Durst said. “The places are timeless—not in an elegant way—but more of just not knowing what time it is. I think that the black and white helps with that, as well as helping it feel more like fiction. In color, it looks a bit more familiar, but in black and white, there is more defamiliarization. That’s the exact area I want to be as an artist.” Durst also pointed out how the use of flash enhances this disconnection from reality. “With flash, it’s not what you see,” he said. “It’s not what the world looks like. It’s something strange.”

Something he enjoyed about the process was the ability to explore communities he knew nothing about. “The camera is such a passport to go places you never go,” Durst said. “That’s something I love about taking photos in the world. They are real people and communities I never knew about. I’m Jewish, so I didn’t grow up in these church spaces and was really curious about learning more about them.”

One of Durst’s goals for The Community was finding the commonalities between all the groups. “What were all these people looking for versus the differences?” Durst said. “In an age of the internet with everything online, why go to the church basement? Why go to these groups? What are you after? What does it mean to be in this physical space in proximity of other human beings, and what meaning can we derive from it?”

After seven years, Durst had a few ideas. “Underlying all these communities, I think there is this search for faith or self-improvement,” he said. “Sometimes just the company of others. In suburban spaces, we are so sequestered.”

Once completed, The Community was published in May 2020 as Durst’s debut monograph. Despite the pandemic’s horrendous timing, Durst wanted to publish it anyway. “I just felt like I needed to get the work out there,” he said.

Durst has one wish for potential attendees of the exhibit: “I hope that the more you look at images, the stranger they become. That nothing is perfectly clarified. I hope that when you’re done going through the exhibit, you’re more confused.”