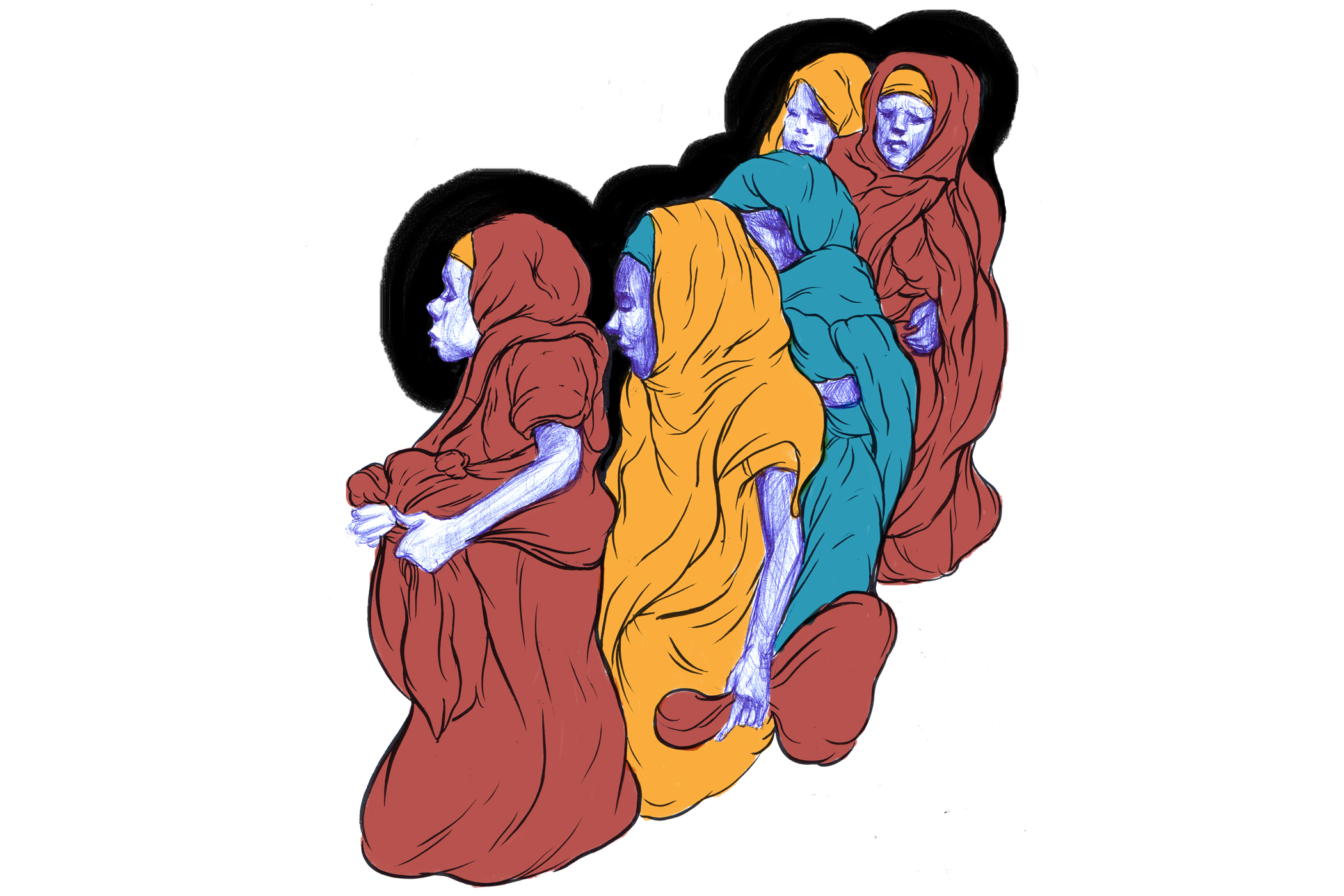

In the past 18 months, Australia has seen thousands of women coming together to expose a culture of bullying and abuse in mining—the country’s economic engine—among other workplaces. Provocation of intense public outrage as well as pledges of decisive action have come from executives and politicians.

Mining and political leaders faced the reckoning of sexual harrasment scandals, which stretch from the outback to the Parliament House.

The matter of workplace harassment, and the respective political response, is one of dire importance, in regards to the country’s upcoming May 21 national election. The ruling conservative coalition faces dozens of accusations of sexual impropriety as well as poor handling of an alleged rape case within Canberra’s parliament building.

Next month, a report will be released by Western Australia that looked into the sexual harasment at mining companies’ operations within the state, widely expected to focus on the internal handling of complaints. Several mining companies already braced themselves for its publication.

“Survivors of sexual misconduct should no longer live in fear, or shame, or silence,” said Elizabeth Broderick, Australia’s former Sex Discrimination Commissioner. “When one woman speaks, others will follow. I call on those who lead in the mining and resources sector to listen and learn from these stories and to step up with strong action.”

Reuters interviewed six women who said they experienced sexual harrasment and/or bullying at an Australian mining site within the past 18 months. Most of the alleged incidents occured after Western Australia’s launch of its highly publicized investigation into the matter, which warned the industry to clean up its act.

According to copies of a complaint and termination letter reviewed by Reuters, Kylie-Jayne Schippers, a maintenance worker at a remote mine owned by Adani Group, was terminated in Dec. 2021 two days after filing a complaint of sexual harrasment and bullying, citing that she had been left afraid to enter the site’s communal dining room.

The letter was filed to her employer, French services contractor Sodexo. It detailed that on Dec. 20 an unknown person circulated a note, falsely claimed to be from Schippers, that offered to give a male engineer sexual favors in exchange for favorable treatment.

Sodexo’s termination letter on Dec. 22 cited “failure to adhere to reasonable and lawful managerial instructions” as her reason for firing, and a review concluded that “no finding of bullying or harassment was substantiated.”

“I was scared, had anxiety through the roof, depression,” said Schippers about the experience that led to her departing from the industry. “They’ve done nothing except swept it under the carpet and got rid of me so they don’t have to deal with it.”

According to Sodexo, Schippers’ complaint “was urgently investigated before being resolved” and her “employment was later terminated for reasons unrelated to the grievance.”

Mining accounts for 1% of Australia’s national output and underpins the country’s economy, with Western Australia providing over half the world’s iron ore. One of the world’s largest untapped coal reserves is Adani’s Carmichael mine in Queensland. However, the sector’s workforce is five-sixths male, and gender parity has had little improvement since its beginnings more than a century ago.

In June 2021, Melissa McLellan, who was a maintenance supervisor for mining giant BHP Group in Western Australia, filed a gender discrimination complaint citing being passed over for an increase in responsibilities. She was suspended from duties three days later for a “fitness for work assessment” citing that she looked tired and could be a potential safety risk.

According to BHP, McLellan’s allegations of bullying and harassment were investigated promptly and were determined to be “not substantiated.” A spokesperson for the company also added that they were committed to creating a safe environment for people to speak, “and we regret that Ms. McLellan did not have a positive experience with us.”

Alongside McLellan and Schippers, most of the women who spoke with Reuters said that their lawyers had either filed or were preparing to file claims for compensation from the companies in question with the Fair Work Commission (FWC), a national workplace tribunal. The FWC declined to comment on individual cases.

“It’s jobs for the boys,” said McLellan, who quit in January, citing bullying. “You’re just second class.”