Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is receiving more public attention these days. April marked Autism Acceptance Month, dedicated to celebrating the diverse experiences of individuals on the spectrum. While the month has passed, our journey of learning and understanding should persist throughout the year. It’s essential to reflect on our appreciation for those with autism, acknowledge the positive strides we’ve taken, and actively work to dispel harmful stereotypes and narratives.

It’s crucial to recognize the distinction between autism awareness and autism acceptance. Since 2011, numerous autistic communities and organizations—such as the Autistic Self Advocacy Network—have shifted their focus from mere awareness and the pursuit of a cure to promoting acceptance and embracing neurodiversity.

Historically, organizations in the autism community have often prioritized finding a cure for autism rather than promoting self-acceptance. Autism Speaks, one of the most prominent autism organizations, is known widely, but its reputation within the autistic community is mixed at best. Many autistic individuals perceive Autism Speaks as a hate group, viewing it as promoting a negative narrative that treats autism as something to be fixed or cured rather than embracing neurodiversity and supporting individuals with autism.

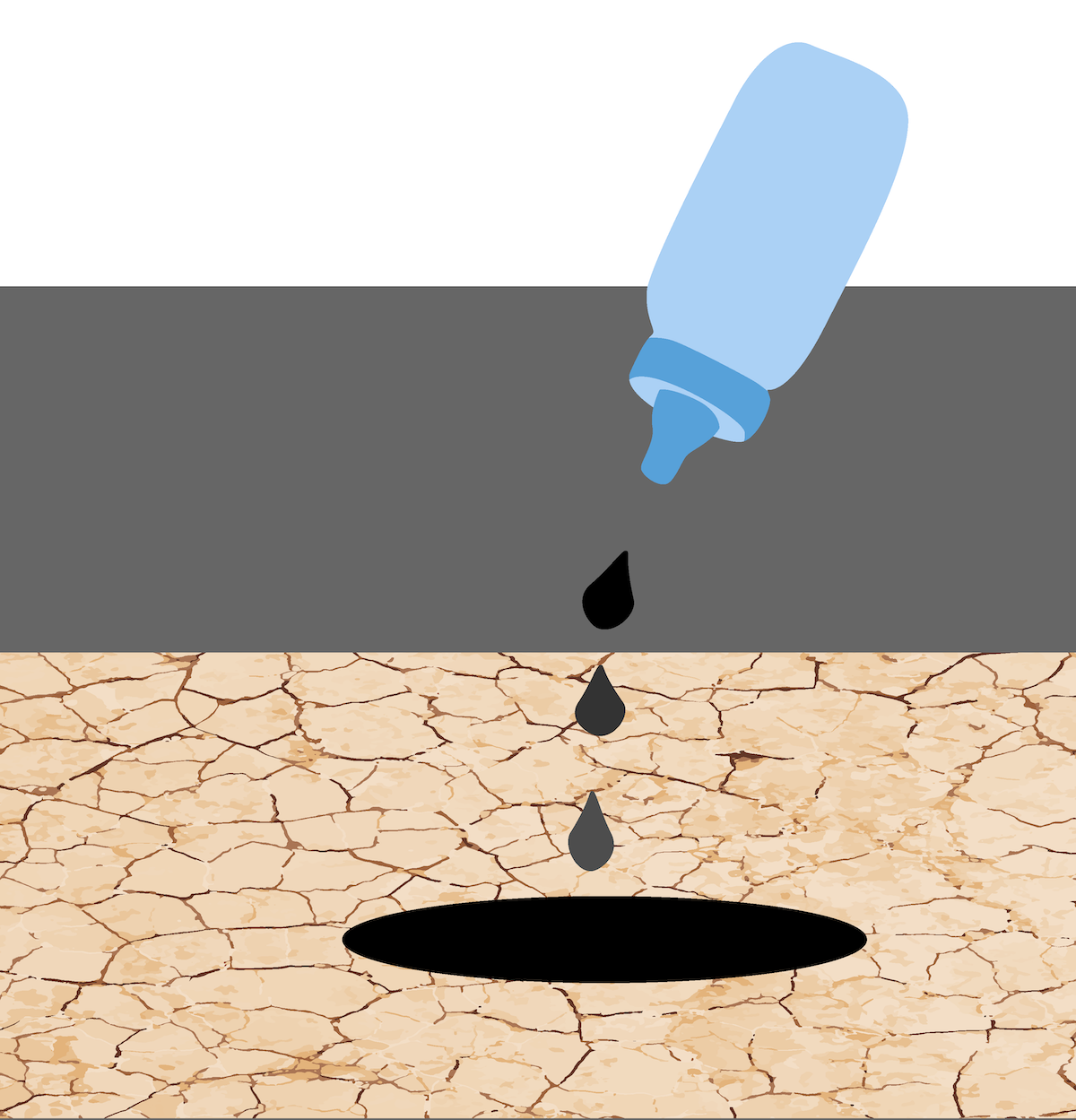

Some criticisms against Autism Speaks stem from their allocation of funds primarily towards advertising that supports Applied Behavior Analysis Therapy, which some liken to an autistic conversion camp. Additionally, they’ve been accused of emphasizing the challenges faced by parents of autistic children rather than focusing on the lived experiences and struggles of individuals with autism.

Cassandra Crosman, an autistic writer and activist, wrote about Autism Speaks’ history, highlighting instances of their involvement with organizations focused on finding a cure and promoting eugenics, as well as allegations of fund mismanagement and making upsetting and stigmatizing public service announcements (PSAs).

Their PSAs have been criticized for perpetuating stigma and fear surrounding autism. For instance, the “I am Autism” PSA employs fear-mongering rhetoric, depicting autism as a rapidly spreading disease more formidable than pediatric acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), cancer and diabetes combined.

The use of disturbing music and threats from the personification of autism implies a need to rescue children from autism, portraying it as a predatory force to be shielded against. This is in stark contrast to how people with autism often advocate for identity-first language and see it as an inherent part of who they are, not as something they are afflicted with.

Autism Speaks also uses a puzzle piece motif from which many groups have moved away. The origins of the notorious puzzle piece originated with the National Autistic Society. “The puzzle piece is so effective because it tells us something about autism: our children are handicapped by a puzzling condition; this isolates them from normal human contact and therefore they do not ‘fit in,’” Helen Green Allison stated. “The suggestion of a weeping child is a reminder that autistic people do indeed suffer from their handicap.”

While it’s crucial to raise awareness about the challenges associated with autism, the metaphor and imagery used in doing so often hurt the autistic community itself.

A study published by the journal National Autistic Society found that puzzle pieces generally invoked negative emotions. Later, the journal also changed its symbol.

Various organizations have opted out of the puzzle piece to something more expansive and representative of autism. The current popular symbol of acceptance is the rainbow-colored infinity symbol, and sometimes the gold infinity symbol for autism, since “Au” is the symbol for gold on the periodic table. The infinity symbol emphasizes the experiences of autistic people as vast and complex spectrums.

Asperger syndrome, a term that was once separated from the autism diagnosis, is now no longer used to differentiate those on the spectrum.

Lorna Wing introduced Asperger syndrome in the ‘80s. It was officially phased in in 1992, but as of 2013, the diagnosis was discontinued.

Given this recent long-standing change, there are still people using the self-identity of Asperger’s, since it’s what they were diagnosed as. This diagnosis dissipating shows the growth within autism research and organizations moving away from the eugenics that plagued its early understandings.

Asperger syndrome is an outdated term that reflects some of the darker past in autism research. Hans Asperger had worked with the Nazis and through his position deemed various disabled children worthy of life or not, sending them for euthanasia through Operation T4.

The male-specific criteria with autism was also established in Asperger’s writings, claiming they were ascribed to the very essence of the male brain and character. Asperger also believed the autistic psychopath to be very valuable in terms of intelligence but lacking in apathy to the community; thus, a cure could be found through socialization.

This history of Asperger’s and the application of this diagnosis is thankfully now obsolete. However, its eugenic roots have lingered in stereotypes portrayed in the media.

We often see autistic people reduced to a very narrow experience in media representations as more intelligent than the average person but utterly oblivious to social structures and signals. Think of Sheldon Cooper from the show The Big Bang Theory or Dr. Shaun from the show The Good Doctor. This reduces the realities of autism to just an antisocial—typically male—genius, which is not what autism is or should be solely represented as. In available popular media, there isn’t really any representation of those autistic people who struggle with verbal communication or repetitive motion or who cannot live on their own.

Sometimes, these portrayals can depict more of the eugenics qualities of Asperger’s research. The character Rory from the 2018 film The Predator leans further into this trope with the line “autism is the next stage of evolution,” which goes more into what some call Aspie supremacy.

Simplified, Aspie supremacy values the valued stereotypes of hyper-intelligent autism and sees it as better not only than other autistic people, but better than allistic people—those without autism—as well. While we should value people, it shouldn’t be based on arbitrary skills but on an inherent value in being a person.

Additionally, with the distinction of valuing and separating autistic people, some use terms like high-functioning and low-functioning. Functioning labels can be an issue when it comes to understanding how autism works, and often is used as a better understanding of how well an autistic person fits into a given society. When people use terms such as low- or high-functioning, there are instinctual differences placed on the expectations of the autistic person and their ability to cope and participate within society. This separation actively creates a disconnect and disservice to the community, placing labels on various people with a spectrum of struggles and differences.

“The practice of not giving separate diagnostic labels to each area of difficulty and lumping co-occurring conditions into one overarching autism diagnosis does everyone a disservice,” said Kat Williams, an autism campaigner.

There is harm with functioning labels, as well, due to the fluctuation of degrees of symptoms; there will be different days, experiences and challenges that can’t fit within the labeling of these two boxes. There is still a lot of debate in the autistic community on the inclusion of those who might have a more challenging time self-advocating and how to advocate for them as needing more constant communicative and social support, especially with a lot of advocacy and representation going up online, skewing what autism looks like. For representation, spaces and attention should be given to the most vulnerable in the community.

There isn’t exactly a perfect fit for this language. However, some autistic people would prefer a shift in the language from functioning to support needs, as it steps away from the internalization of labels to that of accessibility and centering care.

More importantly than ascribing the right and wrong labels, a person’s autonomy should be preserved rather than an assumption of full, independent capability—where they don’t need support—or lack of capability—where they cannot self-advocate.

ASD diagnosis is often geared toward children to find it as soon as possible and offer support and resources. Unfortunately, if it goes unnoticed during that age, obtaining a diagnosis becomes much more challenging.

Autistic adults face barriers to getting a recognized diagnosis. There are various reasons a person believing they are autistic might want a diagnosis, as well as multiple reasons they might not. Late-diagnosed autistic people have expressed feeling the isolation and loneliness of being socially ostracized for being different and not feeling like they belonged. This age disparity is better contextualized with recent studies that explored the mental health of those adult-diagnosed than their childhood-diagnosed counterparts. These insights underscore the importance of ongoing support and understanding for all individuals on the autism spectrum.