Valentine’s Day dates back to 496 CE and has since evolved into a globally celebrated occasion. Throughout history, this holiday has a rich tapestry of cultural, literary and commercial influences which have collectively shaped its development.

Unveiling a fascinating amalgamation of traditions, the story of Valentine’s Day showcases how it has transformed into the widely-celebrated and commercial occasion we recognize today.

When did Valentine’s Day become a celebrated holiday?

In 496 CE, Pope Gelasius designated Feb. 14 as Valentine’s Day. This decision symbolized the papacy’s desire to shift away from pagan traditions—specifically the Roman festival of fertility called Lupercalia, which previously celebrated fertility on Feb. 15. The intent was to reframe the occasion as the Feast of Saint Valentine, transforming it into a religious observance.

It was common for Christians to observe holidays which coincided with other festivities, trading out pagan festivals—such as Sol Invictus for Christmas and Lupercalia—for the Feast of Saint Valentine.

Some believe Rome did this intentionally to help convert pagans to Christianity, while others argue it was the Romans’ way of covering up pagan rituals to make room for Christianity.

The new Christian holiday commemorated Saint Valentine, the patron of love. A triad of stories swirls around the tale of Saint Valentine.

The leading story goes that Emperor Claudius II imprisoned Saint Valentine—a devout Christian when the empire was predominantly pagan before Constantine.

Claudius II executed Saint Valentine in this story on Feb. 14, 270 CE.

One part of the myth includes the jailer’s daughter. Saint Valentine cures her blindness, and she and her family convert to Christianity.

Another account speaks of a bishop, Valentine of Terni. The emperor put him to death in that legend also, making him a martyr.

In a third, Saint Valentine married soldiers. Roman law prohibited warriors from being wed because love distracted them from war. He also wore a Cupid ring on his hand. Soldiers knew him by this signet.

This version of Saint Valentine’s story suggests he may have distributed paper hearts like greeting cards, speaking to the tradition that continues today.

Valentine’s turns through time

Valentine’s festival associations largely remained religiously based until the fourteenth century, specifically 1374–1381, when Geoffrey Chaucer penned the poem A Parliament of Fowls. In it, Chaucer satirizes courtly love in medieval England at the time.

His poem relays three tercel eagles wooing a mate. Each bird confers with the formel, the female, trying to win her wing. The lesser birds are in a frenzy, debating who’s the ideal suitor.

“For this was sent on Valentine’s Day,” Chaucer wrote. “Where every bird cometh there to choose his mate.”

Chaucer also eulogized King Richard II’s marriage to Anne of Bohemia, his 15-year-old bride.

Moreover, numerous Valentine’s customs and practices from the past have been forgotten or lost with time.

Some extant sources mention the Day of Love in passing. Coupling birds were recurring images throughout the medieval period. Playwrights like William Shakespeare hint at such folklore in his play A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In act four scene one, Prince Theseus comes upon four slumbering woodbirds. “Saint Valentine is past,” says Theseus, “And will these four love birds be coupling now?” Many Europeans believed birds mated on Feb. 14.

Although we know very little about medieval celebrations, some letters have survived from the Norfolk gentry—the Paston family. One note alludes to an event akin to Secret Santa.

A group of upper-class peers sat around and drew valentines. Sir William Petre, the Secretary of State—who advised King Henry VIII, Edward VI and Mary Tudor—sent his allotted valentines cloth and gold knicknacks.

Sir Petre included his servants on the list. According to the Paston letters, one year, he drew a maid from his household and, as a result, paid her a quarter’s extra wages on Valentine’s Day. English and French nobility also composed letters to their lovers.

In 1417, Charles d’Orleans delivered the first recorded valentine. At the time, the French and English were fighting the Hundred Years’ War. King Henry V—his adversary—defeated him at the Battle of Agincourt after losing so many battles. The King seized Charles—France’s champion—and locked him up in the Tower of London.

Duke Charles stayed there for 25 years. He often sent his wife letters and poetry. In one post, he calls her his valentine. “God forgives him who has estranged me / from you for the whole year,” the French translation states. “I am already sick of love, my gentle Valentine.”

Charles was an esteemed poet in his time and has remained so to this day. He wrote 500 poems throughout his lifetime.

During this era, literacy raised questions about how individuals—particularly peasants—engaged with Valentine’s Day. While some could read, writing skills were less widespread.

In contrast, the upper and middle classes actively participated in letter writing. However, the cost of quality ink and parchment was exorbitant, making these materials a luxury. Additionally, the writing tools of the time posed challenges. Pens were limited to moving either up or down due to an awkwardly shaped nib.

Writing was cumbersome and time-consuming. Consequently, it remains uncertain how peasants and others celebrated Valentine’s Day—if they celebrated it at all.

Affectionate displays of love weren’t welcome everywhere, however. The Puritans punished affectionate displays outside the home. Colonies in New England forbade hugging and kissing.

Puritan theology believed in married love only. Husband and wife must have shared a dutiful ardor towards each other. A simple peck on the cheek was almost like a proposal, forcing couples to suppress their urges.

Captain John Kemble learned that the hard way. He lived for three years abroad. When he was home at long last, joy overcame him when his wife greeted him. He returned her feelings with a long, passionate smooch—in public! The town threw him into the stocks for three hours.

Greeting cards gained a place in society by the 1720s. Couples also expected an exchange of trinkets by this time. Some gave each other notes written longhand, poems or homemade cards. Many included symbols like Cupid, hearts, lovers’ knots and turtle doves.

Valentine’s day grew in popularity in the seventeenth century. Western countries like Britain and the United States first celebrated Saint Valentine’s love.

Gift-giving was a vital custom, much like it is now. Friends and family gave away spoons and gloves. A small token also expressed affection between a couple. The act showed commitment. Sometimes, their courting lasted a whole year. A fruitful relationship typically led to betrothal.

Love was a public affair in Victorian England. Valentine’s Day became so popular that children went street by street, spending the evening valentining.

They knocked on doors, bagging candy from neighbors and loved ones. Later, the middle class came up with paper cards because, eventually, Valentine’s Day turned into unruly riots. Printed cards as a gesture replaced trick-or-treating.

The business of love

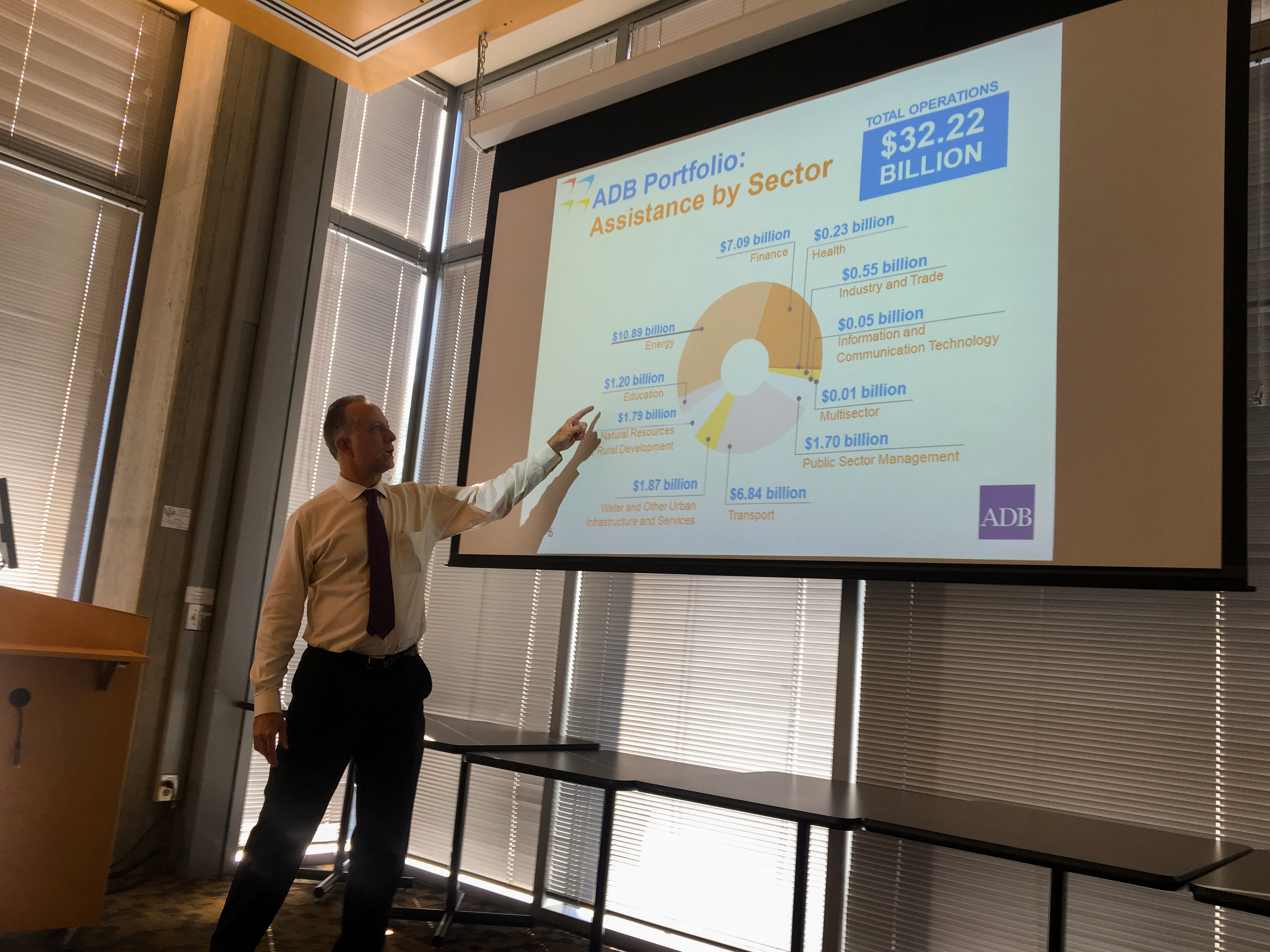

Valentine’s Day entered true commercialization in the 1840s with the mass production of cards in the U.S.

In 1849, Esther Howland published the first popup, Valentine, popularizing greeting cards on Valentine’s Day. Her father owned a stationary store in Worcester, Massachusetts. One day, Esther asked him if he would import paper. She sold him on how trendy and successful the cards had been.

The venture was a family affair. Her father ordered some lace, pictures and other decorations.

Esther hired friends and family for the assembly line. Her brothers sold samples on the road as traveling salesmen. Her friends described the workload as light and easygoing. Some cards had gooey, flattering poems copied from books, decorated in cards with silk, satin and lace. Others had a brief, four-verse poem inside.

Esther had an ambitious business plan. She wanted at least $200 in sales. When her father returned, he came back with exciting news. He had secured more than $5,000 in pre-orders. Thus, Esther’s associates set about fulfilling that need. She checked every card put together at the workshop.

Business boomed in the 1860s, and Esther’s ideas influenced the market. Soon, greeting card companies picked up the idea.

In 1911, Hallmark printed the first color card. Companies then started promoting cards, chocolates and flowers on Valentine’s Day. The chief campaign focused on kids.

Children traded valentines during the school day. Hallmark’s persistent marketing contributed to associating cards and chocolates with Valentine’s Day.

Esther’s handiwork left a mark on Valentine’s Day. Cards have evolved since she debuted the first popup. Vinegar valentines trended in the nineteenth century. Some have verses written in circles or upside down.

Contemporary cards focus less on romantic love and instead on those who have a special place in someone’s heart.

Today, Valentine’s Day is observed in over 30 countries, showcasing its global popularity. Hallmark reported that the celebration has become widespread, with more than 145 million cards exchanged annually. This staggering number doesn’t even account for the additional cards and candies shared in classrooms, highlighting the enduring and widespread tradition of expressing affection on this special day.