As we see an increase in political activism—especially with younger people taking to the street and demanding not to be ignored—the people who want to ignore them will be angry.

We see that across the internet with comments like, “This isn’t how you get support,” and, “What happened to peaceful protests?” There are usually a variety of different messages trying to tear down a movement, because they honestly don’t care and don’t want to see it.

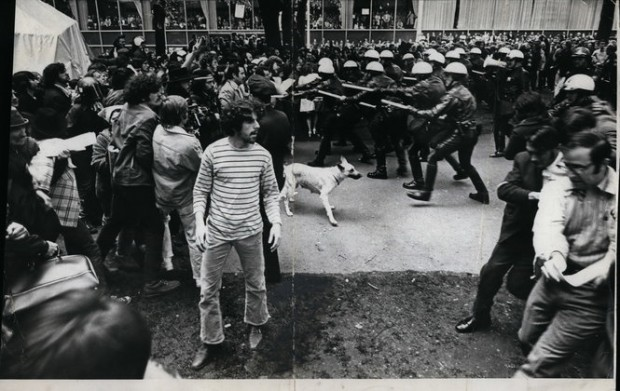

Criticisms of these movements are not new. While the movements’ topics may have changed, many previous movements faced similar backlash and comments.

Although any group can perform nonviolent protest, the focus here is to broadly talk about disruptive events which center on marginalized people—workers, students, people of color, etcetera—and their attempts at demanding liberation or showing solidarity for groups not treated with justice and respect.

A few years back, this would most likely have included the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests. BLM received mass media coverage during protests and demonstrations, which were often labeled as violent riots. This coverage was mainly used to demonize the organization and frame the movement as unjustified.

Now, the focus is on the Free Palestine movement, which has gained international attention and traction as a global protest.

The dismissive response to these protests—with what is seemingly the more moral high ground—gives insight into the pervasive perspective which lacks accurate historical retelling and is ultimately what these protests fight against.

Many comments react to political protests by citing the civil rights movement’s history of being nonviolent and peaceful. However, upon closer examination and comparison with today’s political landscape, it becomes apparent how these historical protests were not entirely nonviolent and how significant parallels exist between then and now.

This criticism often draws parallels to figures like Martin Luther King Jr. but overlook historical facts, such as King himself participating in major highway shutdowns—most famously during the march from Selma to Montgomery.

Comments that shame activists—portraying their collective action as sloppy and lacking decorum—ignore the historical context which these movements are built upon.

In reality, history is repeating itself in terms of criticism, the role of the federal government and the general public’s support level.

During the civil rights movement, 85% of white people believed that the demonstrations were detrimental to the movement, showcasing a historical pattern of skepticism and criticism.

You can call the presentations of protest disruptive and annoying, sure, but what becomes nefarious is the active villainization and criminalization of the political activity of marginalized people and liberation movements.

Though the inconvenient actions of collective demonstrations are pretty standard after football games, festivals and street events, it seemed that—due to the topic of the event—it was worse than a holiday parade inconvenience and thus deserved harsh and cruel punishments.

Moreover, when protests start being called riots, or people believe it is righteous to try to say, “Just drive over them,” it shows how we have started to justify cruel and dehumanizing treatment.

Despite facing backlash, misrepresentation and mistreatment, protests are not diminishing. Instead, they are growing in strength and numbers. The World Political Review has termed the increase in public demonstrations “The Age of Global Protests,” giving a broad overview of various civil unrest worldwide.

In the United States, numerous local and nationwide movements and collaborations exist. Despite receiving less coverage than some prominent issues, the Stop Cop City movement in Atlanta has established direct connections with BLM, Free Palestine, Land Back and environmentalist movements.

Although mainstream media tends to overlook these demonstrations, they are gaining traction and visibility through online platforms.

We are witnessing a growing trend of disruptive actions with increased frequency and higher levels of online engagement. These actions range from spreading information on social media to various collaborations which support and promote online activism. However, there is still a need for tangible, material action.

Online activism carries the issue of black box algorithms and content bubbles. These shield people from seeing what might not involve them by either suppressing tags on certain content or only spreading it to those who are already informed and in the web of activism.

Websites such as TikTok have also made comments trying to explain how the algorithm does not push pro-Palestinian content, and how it’s simply a reflection of the younger user base’s pro-Palestine beliefs. This insight sheds light on the limited support these platforms might have for such engagements.

The humanitarian crisis is gaining support from those directly affected and individuals expressing solidarity. While people are eager to join and show support, there is a recognition of the complexity and risks associated with this step.

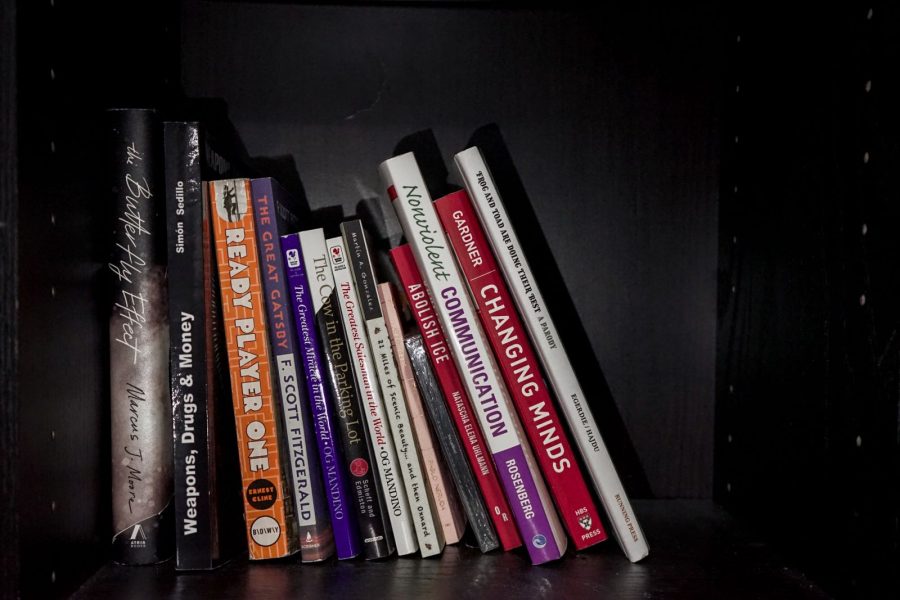

Boycotts are one of the most peaceful forms of activism which people can participate in, yet there are various laws and powerful attempts to create barriers for the creation and expansion of protests. This was expressed in the “IGO Anti-Boycott Act,” or H.R. 3016, which passed last year by the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

An additional misconception about boycotts is that they are ineffective and pointless. However, if boycotts were truly ineffectual, why would proposed bills attempt to establish legal measures to curb boycotting?

The protest style of shutting down transportation—called carpool caravans or simply car caravans—has happened around the country, blocking major highways and interstates in cities like Chicago and San Francisco. Caravans of protesters have even taken place here in Portland, where they caused disruptions in support of Palestine by blocking highways to the PDX airport with around 50 cars.

These forms of nonviolence—labeled as violence—have been around at least since the ‘60s with goals and strategies focused on informing and spreading the message of peace by shutting down and disrupting economic, congressional and labor efforts.

The effort of these movements—which show up again and again—is for liberation. Rooted in the belief that our struggles are interconnected, they carry a rich history from the civil rights era. The central goal was the liberation of all people, which is worth more than a little inconvenience for some.