On Aug. 19, 1936, Spanish fascist forces gunned down the Surrealist playwright and poet Federico García Lorca—he was 38 years old. In doing so, they cut short the life and career of an uncompromisingly creative mind, a man who Salvador Dalí once called “an inventor of marvelous things.”

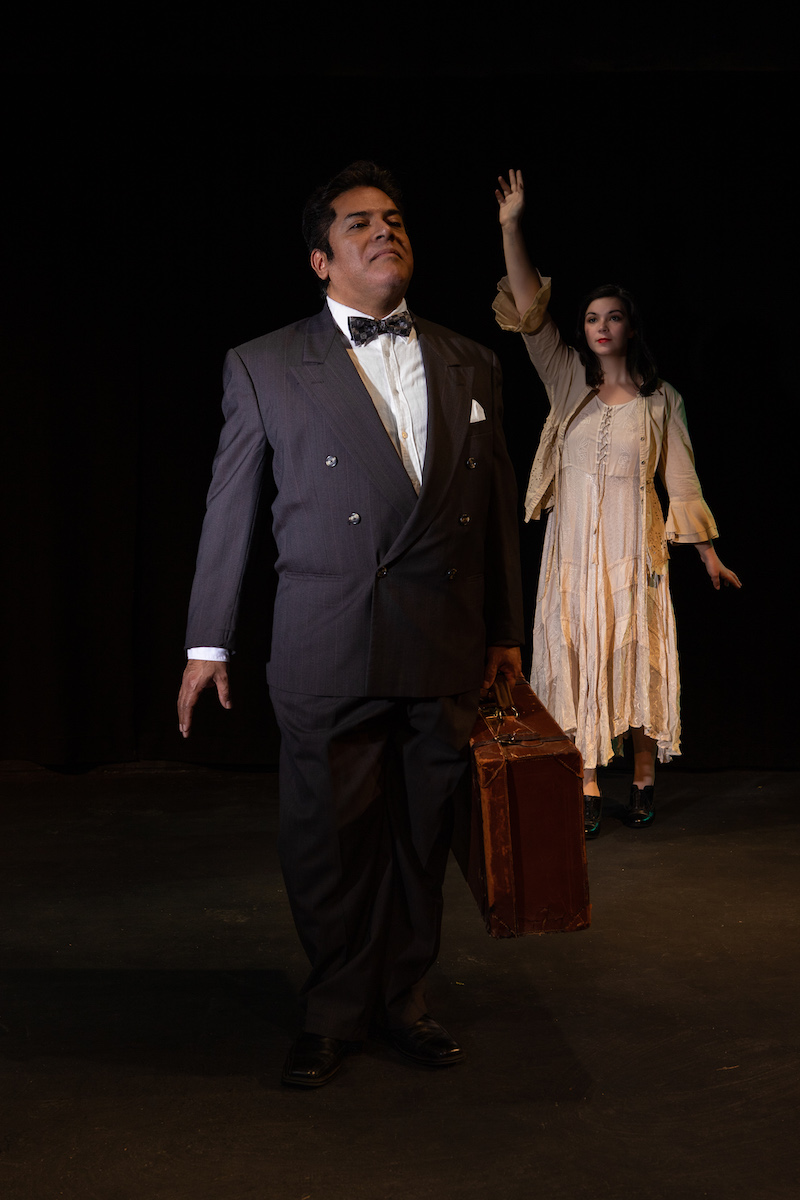

García Lorca’s contemporaries, including Dalí, would live on to make themselves known as international names in the art world, but García Lorca would never have the chance. Now, almost 100 years after his violent death, Portland-based Milagro Theatre aims to shine a light on García Lorca’s tragically short life with a play about the artist called Duende de Lorca.

“If Lorca had lived as long as Pablo Picasso and Dalí he probably would have continued to inspire the theater world as well,” said Danel Malan, the director of Milagro Theatre and the writer of Duende de Lorca.

The play examines García Lorca’s life through dream-like flashbacks while he sits in prison, awaiting his inevitable execution. This style of narrative becomes an inventive framework that the Milagro takes full advantage of, using dynamic light projections to build the settings of each scene in García Lorca’s life. The playwright was closely affiliated with the Surrealist movement, and the play of light and color that makes up the drama’s scenery borrows heavily from the artistic history of Surrealism, even incorporating García Lorca’s own work into the projections.

“We’re projecting films that we believe he was a part of, that he was represented in,” said Lawrence Siulagi, the play’s director. “Some of his abstract, more emotional pieces are going on, [and] because this is a dream, there’s a lot of visual elements going on in the background.”

Siulagi, who has several years of experience in stage lighting and projection, said that the hardest part was striking a balance between the drama unfolding in the play, and the visually-arresting display in the background.

“Projections can quickly overtake what’s going on onstage [but] in the sets that I’ve worked on it’s incorporated so that you don’t notice it, you just notice the feeling,” Siulagi explained.

Careful sound design is also integrated into the play’s structure, and the sounds of gunfire from other executions outside García Lorca’s prison cell interrupt the dream sequence, grounding the audience in the reality of the artist’s situation.

Despite the fact that García Lorca was killed nearly a hundred years ago, Malan is careful to stress that his story is still more timely than ever. García Lorca was gay, and this fact—combined with his liberal and pro-democracy politics—led to him being intensely targeted as an individual. Malan points out that the homophobic origins of his killing have only recently been addressed, and the Spanish government only publicly acknowledged that he was targeted for his sexuality in 2016.

Even today in our own country, according to Malan, some of the educators in schools that present her plays in are unwilling to engage with the fact that García Lorca was gay, choosing instead to focus solely on his work.

“You have to realize that the work, his body of work, comes from him, and you have to understand him in order to understand,” Malan said. “He’s a writer, how can you respect his work without respecting him?”

In one extreme case, Malan presented a play in a school where the principal expressed their concerns bluntly: “Are you going to teach the kids how to be gay?”

Encounters and attitudes like these underscore the importance of both educational theater and García Lorca’s life story and, in large part, this spirit of outreach and awareness is at the core of Malan’s playwriting.

“I have always believed that theater is inherently political,” Malan said. “I don’t think there’s a single playwright who doesn’t make at least some kind of either social justice or political comment in their work. What would be a play with no message?”

With Duende de Lorca, Malan would like people to come away with an understanding of García Lorca’s uncompromising desire to be himself, and not just focus on what seems like a sad message of a poet assassinated.

“I hope what audiences take away from it is that this is a man who, in the end, followed his dream and spoke out,” Malan said.

Siulagi added that despite the play’s tragic underpinnings, he would like people to understand who García Lorca really was, and to leave the theater knowing it was a tragedy, but wanting to go and look up his work.

“I wanted to make sure the focus was on the love, the compassion,” Siulagi said. “He cared about politics, he cared for people. He used his words, his poetry as a way to express himself to the world.”

Duende de Lorca will be playing this month from Jan. 13–23 at the Milagro Theatre.