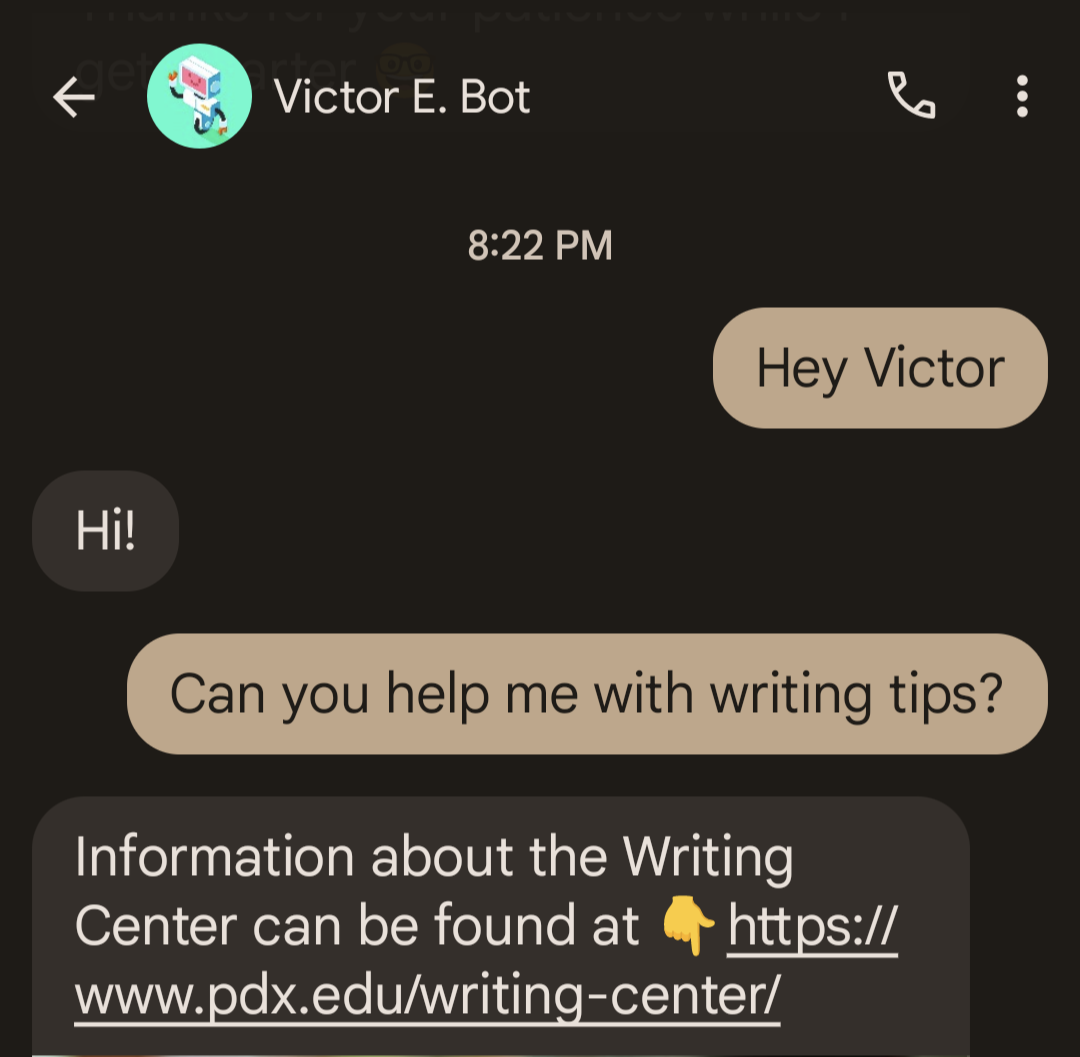

Dr. Christof Teuscher is a professor of engineering and computer science at Portland State. His research pulls from many different fields to address societal problems. His approach applies unassuming techniques to pervasive issues in fields of study ranging from medicine to artificial intelligence (AI). His most recently published article is “A Novel Deep Learning, Camera, and Sensor-based System for Enforcing Hand Hygiene Compliance in Healthcare Facilities.”

In 2016, he set a record for completing the 700-mile, rugged and largely-unmarked Oregon Desert Trail fully self-supported. He completed the endeavor in 17 days and 15 hours, averaging around 40 miles per day. He climbed Mount Adams, and trekked nearly 140 miles to Mount Hood before climbing its peak in less than 70 hours. Teuscher recorded his adventures and kept an exhaustive record on his website.

Portland State Vanguard spoke with Teuscher to learn more about his research and background.

VG: How do you think the environment in which you grew up shaped you?

Teuscher: It shaped me quite dramatically. I grew up in a very small town. There were about 1,800 folks, and it was very rural. There was lots of farming. Most people didn’t go to college. Most people would do an apprenticeship. So I did that—an apprenticeship as an electronics engineer.

The Swiss educational system is quite… flexible in the sense that there’s multiple paths you can explore, even if you don’t go to college.

You can go to technical high school. You can still go to a higher educational institution. So there’s various paths that allow you to explore all kinds of different degrees and certificates.

After four years, I knew I didn’t want to be an electronics engineer for my entire life, so I went to college. I then decided to get a degree in computer science from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. I think it was a really good choice.

At that point, I didn’t know what research was at all. And over the summer, one of my professors asked me, “What’s your plan? Do you want to do an internship in my lab?” I said yes because I didn’t have anything else to do.

So, I got to know what research really was in an academic environment. They sent me to a conference in the [United States]. It was my first, and I presented a paper. It was really exciting.

VG: Was that your first time in the U.S.?

Teuscher: That was my first time in the U.S. First time at a scientific conference. First time presenting. It was a lot of new things. I had to learn quickly. I didn’t know anything about this at the time. I had no master plan. I thought, “Once I get my degree, I’ll go back to industry and work.” But then suddenly, I learned about PhD programs and sooner or later I was in one and eventually finished.

That wasn’t my plan at all. It was just happening because I had these opportunities. My mentors believed in me and gave me opportunities that I didn’t have or didn’t know even existed.

That’s something I try to do here at PSU. My door is open for students to knock and ask for opportunities that I’m more than happy to provide. So, I’ve worked with a lot of undergrad students and high school students. It’s a way to give back and really provide opportunities that others may not have or may not even know about.

VG: Can you tell me more about your endurance sports?

Teuscher: Endurance sports came much later, basically after my fortieth birthday. A friend asked me whether I wanted to do a 50k run. I didn’t even know what that was, and I just said yes. Then I realized it was actually longer than a marathon.

I started training for that and then really got hooked. I figured, “Okay, now that I have the fitness to do 50 kilometers. There’s 50-mile races, and there’s 100-kilometer races, and there’s 100-mile races, and there’s more than that.” So I just kept going.

It’s very much related to my research because I tend to push limits with the research we’re doing in terms of computer capabilities, [or] exploring new things that computers can… or should do and will do in the next couple of years.

Endurance sports are very similar in that sense. You’re pushing your own physical and mental limits. It’s also a way for me to be a role model for students. I have pretty high standards. I expect students to work hard. So to me, that means I also work hard. If their faculty advisor does crazy things, maybe that’ll drive them to also do things a bit out of their comfort zones.

VG: Do you tend to say yes more than you say no?

Teuscher: That’s a difficult question. I used to say yes a lot, especially earlier in my career when there were a ton of opportunities. I just said yes to them until several folks that were my mentors and those I worked with told me, “Look, Christof. You gotta learn to say no because you cannot be successful everywhere.”

I was really starting to be spread thin in so many ways. I see that with students in my lab now. If you say yes to too many things, you’ll likely fail, and your whole career can fall apart. I think I learned the hard way to say no, and now I’m much more selective in terms of what I say yes to.

VG: How do you know when to say no? How do you know when enough is enough?

Teuscher: That’s difficult. The Oregon Desert Trail is a good example of where I was physically forced to stop. I just couldn’t walk anymore. I had an injury, so that’s almost the easiest situation where you just can’t continue.

But there are other situations where it’s more about assessing risk, and figuring out whether or not I’m willing to take those risks. They are sometimes difficult decisions. Sometimes I regret my decision. I think, “Oh, I could have done it.” But in the moment, it’s really hard to assess if it’s worth the risk or not.

I have examples where I turned around or quit because I felt like I wasn’t willing to take that sort of risk in terms of weather, in terms of food, in terms of safety. Sometimes it’s poor planning. Sometimes I think I can do it in, let’s say five days. I pack five days of food, but then it turns out I actually need seven days.

I have a ton of examples where I quit. But these are—to me—learning experiences, where the next time you do it better. You go again, and you’ll likely be successful. I think I’m successful because I’m persistent. I try again. While others give up and don’t go back, I often go back.

VG: How do you train for something like that?

Teuscher: It depends. Some things need very specific training. Like for this recent race I did in Italy—Tour de Glacier—it has 100,000 feet of elevation gain. That’s huge. So you really need to train for ups and downs. It means I’m doing a lot of Mount Defiance in the gorge, because that’s one of the steepest and tallest peaks in the gorge.

VG: You said you got your start with this in ultra running, but you’ve also said that it’s lost its appeal. How did you come to that conclusion?

Teuscher: I wouldn’t say lost its appeal. To some extent, perhaps. It changed. I’m chasing different things. That’s partly because I’m getting older. I used to run quite competitively for long distance races.

When you’re a little bit older, I think you’re in better shape mentally than some of the younger folks, who are much stronger physically. Mentally, though, they may not have the experience. And so there’s a sweet spot. I was just at the end of that period. I can’t really compete with a 30-year-old.

VG: And what’s your next adventure?

Teuscher: I don’t know. That’s always a good question. I have a long list of things on my radar. I usually decide based on the weather or depending on my meetings and availability.

Some things need more planning than others, but I have a list of adventures that I could pull off in a couple of hours. They’re planned to the last detail, so I can pull up my notes and basically just go.

VG: Why is it so important for you to record these expeditions and share them with the world?

Teuscher: There are two aspects. One is to inspire others. People watch these movies, and they may do an adventure just because they saw my little clip.

And two, making movies—it’s almost like having a buddy. I can talk to my camera if things don’t go so well. I can share my thoughts with the camera. So there’s almost a social aspect to recording the expeditions. Doing it changes the moment, makes it more lighthearted.

VG: What’s been the biggest innovation in your field in the last five years?

Teuscher: Definitely the rise of AI and machine learning and neural networks… Deep learning became this huge thing, not because the models were new, but because we had more computing power.

We could suddenly simulate scales of a network that we were not able to simulate five or 10 years ago. But the foundations are still the same.

It goes back to [Alan] Turing, [Frank] Rosenblatt, and [Donald] Hebb—all of these early pioneers of neuromorphic systems and computing. Not much has changed foundationally. It’s the scale that is different. Clearly, that’s pushed the field to a whole new level. Now everybody knows ChatGPT.

VG: Hardly anyone knew what a large language model was. Now we talk about it every day. What do you think the gaps are in the layman’s understanding of AI?

Teuscher: It’s hard to say. People are afraid, but AI has been helping us for decades—quite literally. You wouldn’t fly a plane without it. There’d be no reservation system without it. Voice recognition wouldn’t work without it.

So ChatGPT is really only the tip of the iceberg. People are afraid society will collapse because of X, Y and Z, but AI is already everywhere, just not out in the open like ChatGPT has become.

VG: Is there anything in your field that you’re particularly excited about?

Teuscher: What comes next in terms of humans being replaced by machines? I think we have numerous examples now where machines do much better than humans.

This goes back not just to ChatGPT, but way earlier. Machines started to do better in many domains. There are new challenges, too. How will humanity use AI? Will we be able to live without these tools in ten years?

VG: What sort of research are you and your students working on right now?

Teuscher: We’re really trying to push computers into new domains and have computers do things differently, better, faster, more… efficiently. We’re really in no man’s land. We don’t really know what will work. My students mostly write computer-code-run simulations, and run hypothetical models of hypothetical computers to see what they can do.

A lot of it involves machine learning as well. And these AI models use a lot of power. Data centers are very power-consuming. So everybody is trying to build computers that are less power-consuming.

We also explored DNA computing—using biological building blocks to essentially build computers. That can have or could have, huge implications for personal medication.

It would be really cool if you [could] swallow a smart machine that finds your cancer cells and kills it. There’s sort of these science fiction-y projects that we have, where we’re not building machines out of silicon components or traditional computer building blocks but out of DNA, out of enzymes—you name it. It’s amazing.