Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro faced backlash after announcing a bill earlier in February 2020 that would allow development on indigenous lands.

The initiative bill would open Indigenous lands to commercial agriculture, mining, ranching and tourism for the first time since they were banned in the country’s 1988 constitution. Indigenous leaders have called this bill a political project of “genocide, ethnicity and ecocide.”

The bill includes a credit line intended to support Indigenous farmers who have established soy plantations on their reservations.

According to Reuters, Bolsonaro said the credit line will allow Indigenous farmers to buy seed, fertilizer and machinery for the plantations, even though these plantations are illegal on Indigenous lands. Bolsonaro believes this credit line will also aid Indigenous communities by decreasing poverty and integrating them into society.

“Together we will integrate these citizens and value all Brazilians,” Bolsonaro stated in a tweet on Jan. 2.

There are 690 recognized territories for Indigenous populations in Brazil that cover approximately 13% of Brazil’s land mass. These territories are home to approximately 900,000 Indigenous people from 305 tribes.

The bill will give Indigenous communities veto rights for mining practices. However, actions taken for energy exploration such as hydroelectric or thermoelectric plants only require the government to consult communities first.

“It is not enough for the land to be rich if the people living in it are poor,” said Ônyx Lorenzoni, the president’s chief of staff at a ceremony celebrating Bolsonaro’s 400th day in office according to AP News. “Brazilian tribes will have the right to choose, like any citizen, how its wealth will be managed.”

The introduction of this bill comes following a 2019 survey that found “86% of Brazilians disagree with the permission for mineral exploration companies to enter indigenous lands.”

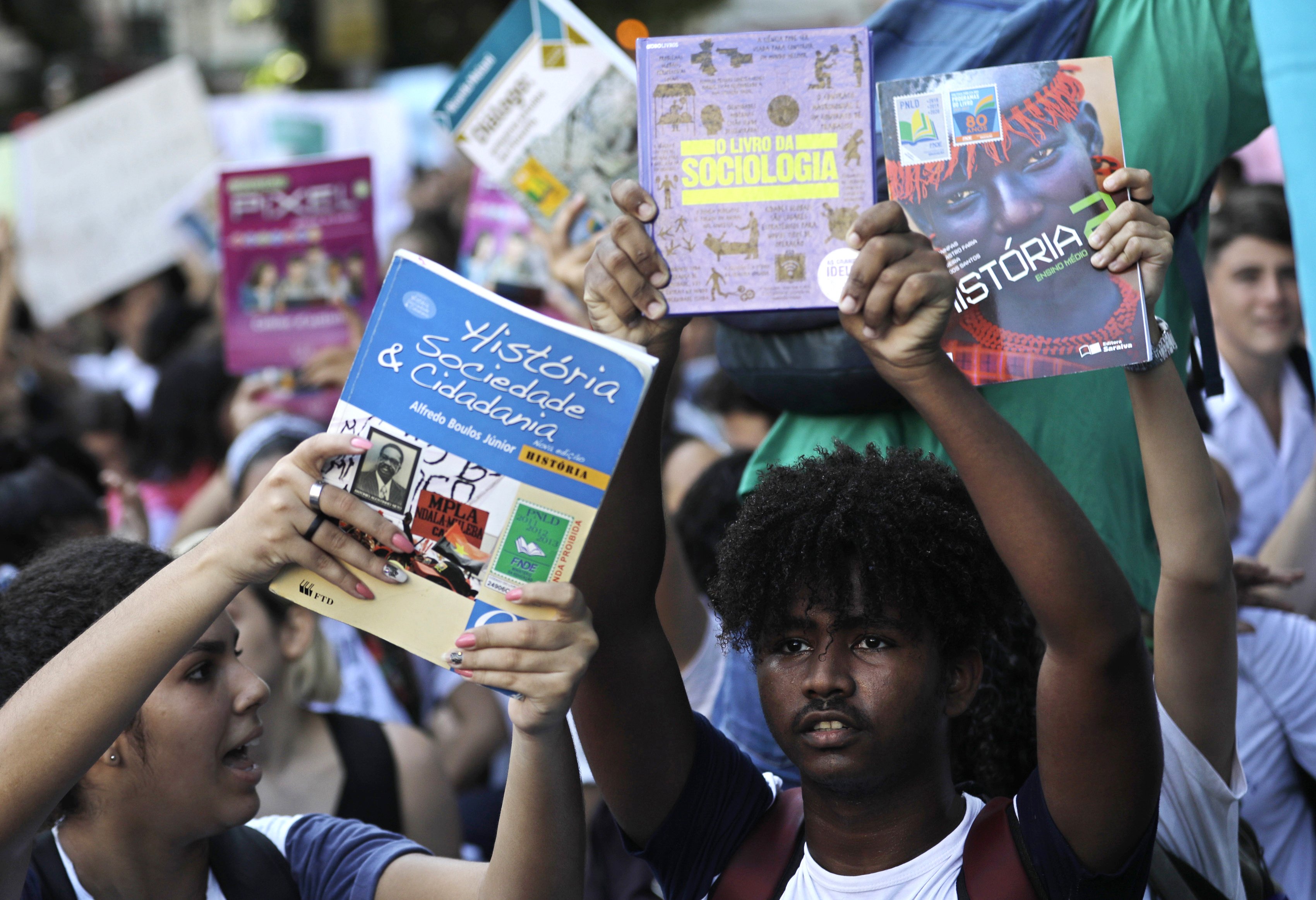

“Bolsonaro is clearly trying to create division between us, but the majority of us are represented here and are against the bill,” said Sonia Guajajara, head of the Coalition of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB).

Indigenous communities from around the country have been speaking out against the commercial use of Indigenous lands since Bolsonaro took office in January 2019.

“[APIB] comes to the public to express its vehement rejection of the displays of visceral hate and racism that the Bolsonaro government has, since its first day of government, routinely and publicly expressed against the indigenous peoples,” the APIB stated in a response to the bill on their website.

This is not the first time Bolsonaro has pushed for policy regarding Indigenous people in Brazil. In 2018, following his election, Bolsonaro said, “As far as I am concerned, there is no more demarcation of indigenous land.”

In March 2019, Bolsonaro attempted to pass another bill that would have allowed mining on Indigenous lands.

The new bill followed the Brazilian government’s decision to name Ricardo Lopes Dias, a former evangelical missionary, to head a department responsible for protecting uncontacted and recently contacted tribes.

“Devoid of any experience in indigenous policy, this new appointment at Funai [the Brazilian Public Foundation for Indigenous People] represents yet another act against indigenous rights,” stated Indigenistas Associados (INA), an association of civil servants from Funai in an open letter.

“The risks of contact are of contamination by disease, as often happened in the past,” said Marcio Santilli, former Funai president, to AP News. “And in the case of evangelism, there is the risk of attacking their ethnic identity.”

“The Bolsonaro government’s direct hit has now come upon the peoples in voluntary isolation, imposing their perverse ideology of integration and assimilation with the appointment of Missionary Ricardo Lopes,” Guajajara stated in a tweet.

These policies mimic worldwide historic patterns of claiming indigenous lands by non-indigenous individuals.

“The privatization and ownership of land is a colonial mindset,” said Nia Williamson, a PSU student majoring in Indigenous Nations Studies. “The separation of people and land was and continues to be a tactic of genocide against Indigenous peoples. Disguising them as policies or bills just further enables this.”

“Our relationships to the lands reflect our relationships to our people,” Williamson said. “The balance of taking care of and being taken care of has been devastated by colonialism, and you can look no further than out a window to see that.”