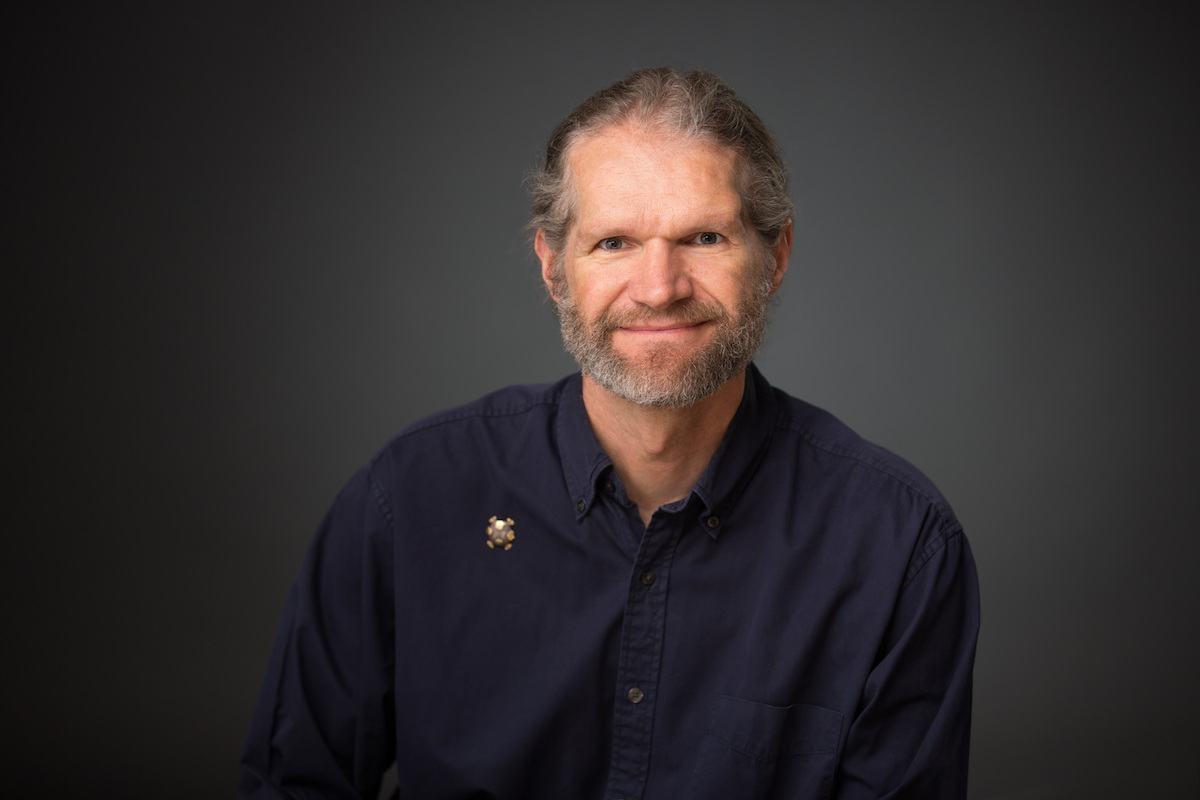

Portland State has its very own virus hunter—Dr. Ken Stedman, professor of biology. Stedman has been recognized twice in the last few months for his research and ability to communicate complex scientific topics to the public. The awards are the Advanced Research Impact in Society Award, 2022, and the PSU Presidential Career Research Award, 2023.

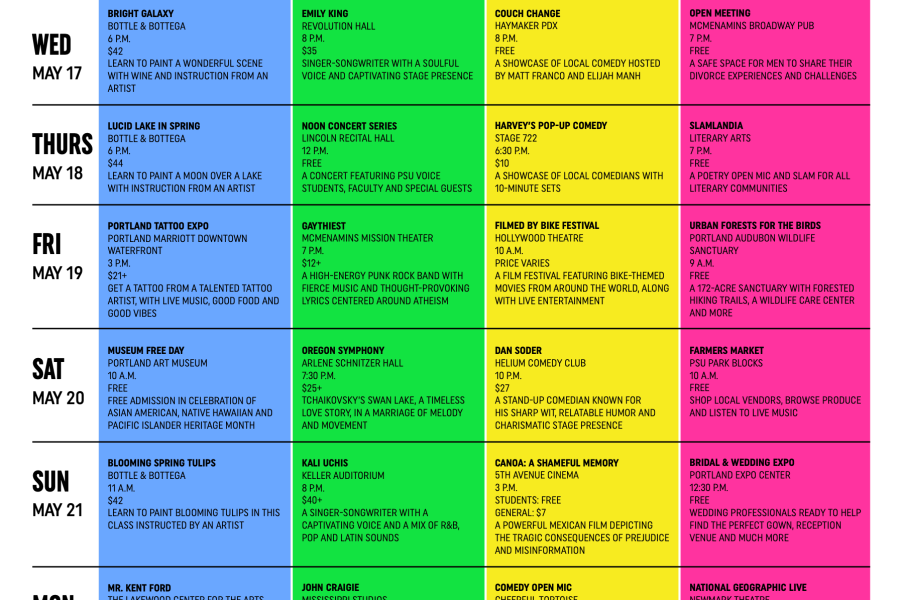

Stedman will discuss his research during his talk titled “From Extreme Viruses to Better Vaccines: The eXtreme Virus Lab” on Wednesday, May 10 at PSU.

The primary focus of Stedman’s research is on so-called extreme viruses—thus, it is fitting that one of his many titles is Virus Hunter. “That’s what we do—we go to some of the craziest places on earth and look for viruses, particularly volcanic hot springs,” Stedman said. “And so that’s been the focus of our research for 20-plus years now, [hunting] viruses in extreme environments.”

Traditional virus hunters are worried about pathogens, but these hunters have bigger concerns. “We’re worried about falling into the environments that these viruses [are found] like volcanic hot springs [composed of boiling acid] 170 degrees Fahrenheit and pH 2,” Stedman said.

How can something survive in these conditions? This question inspired Stedman to study extremophiles—organisms living in extreme conditions—known as archaea and the viruses that infect them. Stedman explained that archaea look like bacteria but are genetically more related to the branch of life that humans belong to, and even share a common ancestor with us.

“We are cousins,” Stedman said.

PSU is the home of the world-renowned Center for Life in Extreme Environments, better known as CLEE. This was one of many reasons Dr. Stedman decided to come to PSU in 2001 to further his research of extreme environmental organisms.

About once a year, Stedman and his students travel to Lassen Volcanic National Park in Northern California to collect samples of the archaea that live there, along with the viruses that infect them. In addition, they visit Boiling Springs Lake right off the Pacific Crest Trail each summer and have been going there for about 15 years. Stedman said that the Park is gorgeous and “a great way to get some… interactivity outside of the research lab, outside of academia” for the students.

It was Stedman’s early career experiences in Naples, Italy, going to hot springs with his supervisor, that inspired him. He called the experience “a real epiphany, because all of the work I’d done before was lab work, very sort of abstract, is probably the best way of thinking about it… so, this was real. I really felt that I had a connection to the environment.”

At PSU, Stedman tries to pass that experience along to as many of his students as possible by bringing 10 to 20 students on his virus hunting trips to the hot springs each summer.

Stedman described an ongoing project that about half of his lab is currently working on in his eXtreme laboratory. It is a virus discovered while conducting genetic analysis—known as metagenome sequencing—of the environment from Boiling Springs Lake.

This virus is unique because its genetic material, or genome, looks like it is derived from RNA and DNA. “It’s a circular DNA, but one half of the genome that’s DNA is really clearly related to RNA and RNA viruses,” Stedman described this atypical virus genome. “Somehow these two things got together, and we still don’t know how that happened [even though] we discovered it, 10-plus years ago. But really fascinating. And this is something that nobody really believed could happen, but we found it. It’s there.”

Stedman explained what they do in his lab, eXtreme laboratory. “We do a lot of really standard kinds of work,” he said. “We’re just looking at non-standard kinds of things like these extreme viruses. And so there are some things that we do which are a little bit different.” One example of this is working under conditions of boiling acid. Stedman said that more than 100 students have worked in the eXtreme lab, and he finds these students to be a source of inspiration.

When asked how he began doing vaccine stabilization work, Stedman explained that he and his student Jim Laidler researched to look for fossilized viruses and how to detect them. One of Laidler’s first experiments was to create an artificially fossilized virus. “They became fossilized, mineralized, but that process was reversible,” Stedman said. “And so we could coat the viruses in silica, inactivate them and then un-coat them and activate them—we call this the zombie virus project.”

Because of Laidler’s background in medicine, the lab decided to look at the stabilization of vaccines using similar methods, and it was this line of research that eventually led to Stedman’s startup company.

Beyond research, teaching and outreach, Stedman has started a company called StoneStable, LLC. This company is based on his research into the thermal stabilization of vaccines using the silica coatings technique that he worked on with Laidler. Because most vaccines require refrigeration, which is often unavailable in developing countries, this could be very advantageous to the transportation and delivery of vaccines into these countries.

Stedman is currently looking into the structure and genetics of the SSV virus—one of his favorite archaeal viruses. As he held up an enlarged model that looked something like a bumpy lemon, Stedman explained that the virus is “getting put together because it gets back to that question about—what is it about the extreme environments and what is [it] about these viruses that allows them to survive within these conditions.”

Stedman will teach a PSU course, Advanced Molecular and Cell Biology Research Techniques, BI-431—commonly known as “mutant viruses from hell”—which will be offered in the spring.

“So what happens with that class is we make a bunch of mutants,” Stedman explained. “We don’t know what those mutants are, and then we give them to all of the students in the lab, and then over 10 weeks they tell us what those mutants are, and let us know if they work—[if] they’re still making viruses and if it’s doing something weird to the virus otherwise. And so that’s been really fun. I have a blast.” Stedman said that his teaching and students often inspire his research.

He will continue his research of the RNA/DNA virus identified from the metagenome studies. “We’re really interested in how that happened,” Stedman said. “We’re also very interested in what these viruses actually infect… also just the evolution and what’s going on in this process because this sort of, you know, DNA and RNA coming together is not supposed to be something that happens. And so we’re interested in also looking at the evolutionary aspects of that, as how frequently does it happen?”

He will also continue his virus fossil work. “I’ve been talking to some of the people at NASA maybe to think about this new technology, partly because they’re sending microscopes to Mars,” he said. “And so if they’re looking on Mars and they see something that looks like a virus fossil, that would be, you know, [a] really good indication that there’s a host and there’s some kind of life on Mars.”

Despite his own contributions, Stedman was careful to emphasize the collaborative nature of research. “It’s been a great group effort,” he said. “You know, everyone is interviewing me, but it’s really about the whole group. I just wanted to emphasize that that’s the case.”