The Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education (OJMCHE) reopened this summer after a four-month period of renovation. Alongside three core exhibitions which focus on Oregon’s Jewish community and the state’s history of discrimination, OJMCHE has added a new core exhibit, Human Rights after the Holocaust, as well as a temporary exhibit—The Jews of Amsterdam, Rembrandt and Pander—open through Sept. 24.

The recent installations emphasize the importance and timeliness of educating people about the Holocaust in the present day. The narrative that this genocide was a finite, anomalous event, far removed from the present day is erroneous and poses a threat to democracy.

The Holocaust started long before 1938. Years of antisemitism, aggressive nationalism and complicity to xenophobic ideologies established a basis for state-sponsored mass murder. Throughout these two exhibitions, OJMCHE traces the Holocaust from the seventeenth century to genocides which echo into today.

The Jews of Amsterdam, Rembrandt and Pander traverse nearly 400 years of Jewish history in one particular place—Amsterdam. This story starts with Rembrandt van Rijn, born in the Netherlands in 1606.

Rembrandt’s Amsterdam represents the splendor of the Dutch Golden Age—an era of newfound wealth and cultural renaissance. This prosperity was doubtless due partly to contributions made by the large influx of Jewish immigrants, who sought refuge from the persecution suffered in wider Europe and the Middle East—particularly in the Spanish Inquisition.

“Amsterdam promised religious freedom of practice to all comers,” said Bruce Guenther, OJMCHE adjunct curator for special exhibitions. “So for 150 years, the Jewish community enjoyed a freedom unseen elsewhere in the seventeenth century. Rembrandt is a witness to that.”

This exhibition showcases 22 of Rembrandt’s etchings depicting the tradition and culture of Amsterdam’s thriving Jewish community. Rembrandt was not a Jew—yet his integration and solidarity within the Jewish community are tangible in his works and unfortunately unique among non-Jewish artists of his time.

“It’s one of the first moments in European art history where the humanity of the Jew was represented,” Guenther said. “Before this, before the medieval period, they were, of course, discriminated against—they were not represented as human.”

The works illustrate stories and figures of the Tanakh—often modeled after real people in Rembrandt’s community—as well as prominent Jews who commissioned portraits from the artist.

Juxtaposing Rembrandt’s celebration of the Jewish presence is six large oil paintings documenting their absence. These are the works of acclaimed Portland artist Henk Pander.

Born in the Netherlands in 1937, Pander experienced the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam as a young child and the aftermath of the city ravaged by war. At age 27, Pander relocated to Portland, where he remained until his death in April of this year.

At first glance, this colorful series presents a charming Dutch cityscape—overlaid on crimson sunsets and trees shedding Autumn—and yet the paintings transform with a closer look. The window panes are broken glass, tree branches wilt at contorted angles and what seemed like a sunset is actually flame. Most ominous of all, the city is deserted.

This was the thriving Jewish community of Rembrandt’s time. Pander paints the empty streets and abandoned buildings of the Jewish quarter as testimony to the atrocity he witnessed.

“The buildings provide mute witness to the destruction of the Jewish community in the Netherlands, where 75% of the population were murdered and did not return at the end of the war,” Guenther said.

“That’s the contrast,” Guenther said. “The optimism and the solidity of the Dutch Golden Age and Rembrandt who witnesses the pinnacle, and Pander who was a witness of the end.”

Entering the room adjacent to this exhibition, visitors will find the museum’s new core exhibition, Human Rights after the Holocaust. Here is where Judy Margles, executive director of OJMCHE, quoted Stanislaw Lem in a recent media preview.

“I believe that this Holocaust has not yet ended,” Margles repeated. “That is to say, yes, in a sense, it ended with World War II, but it keeps reappearing in various forms and versions here and there. What about Cambodia? Strange efforts to make a people happier by exterminating half of the nation. All this is an extension of the Holocaust.”

As much as each generation wants to believe that they would not abide by the manmade atrocities that history has revealed us culpable of, this exhibit exposes the contrary.

“We’re constantly asking the question, ‘What lessons have we learned from the Holocaust?’” said Scott Miller, the OJMCHE guest curator and former chief curator at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. “‘What lessons have we not learned from the Holocaust?’ And this exhibit, I think, begins to give some of the answers.”

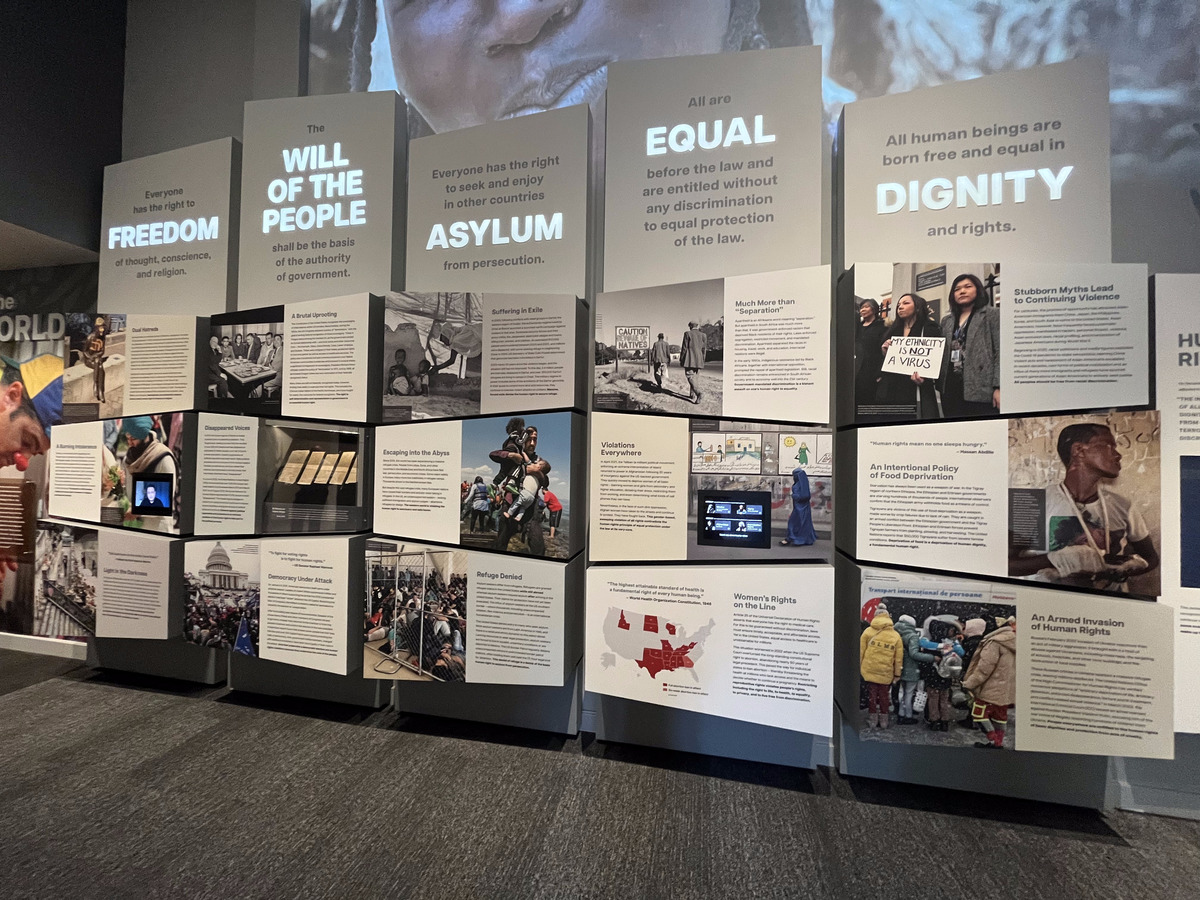

The concepts and language surrounding genocide and human rights were standardized as a result of the Holocaust. The United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948. OJMCHE’s Human Rights after the Holocaust examines five fundamental human rights and how various communities fail to respect them.

For example, Article 14 of the UDHR states that “everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.” The exhibition outlines various instances in which countries deny this right.

In western Sudan, Darfur’s civilians suffer levels of violence which recall the 2003 state-sponsored genocide in this region. “Ethnically motivated attacks, systematic looting, rape, and aerial bombardments,” name some of the atrocities reported by the UN. While an estimated two million South Sudanese have fled, millions remain internally displaced.

Denial of refuge is an ongoing issue, particularly in the world’s most developed countries. This exhibition identifies the western world’s complicity as innocent neighbors suffer. Many European Union countries limit refugee arrivals at highly disproportionate rates compared to their non-EU counterparts, refuse entry to asylum seekers or confine them to camps and detainment centers.

The U.S. is no better, with a system so under-supported and restrictions so stringent that even the few who arrive at consideration may have to wait years in unmanageable legal limbo.

This issue is one of many local human rights violations addressed by Human Rights after the Holocaust. Others include Islamophobic and antisemitic violence, restricting reproductive rights with the overturning of Roe v. Wade and undermining the democratic election during the Jan. 6 insurrection in 2021.

The exhibition highlights the nature of genocide as a multifaceted atrocity that evolves from the gradual and cumulative deterioration of human rights. Genocide indeed happened again after the Holocaust, and it still happens now.

Human Rights after the Holocaust outlines some grave abuses, including the Cambodian genocide in the 1970s, the Rwandan genocide in the 1990s and the ongoing genocide against the Uyghur people committed by the Chinese government.

The exhibition’s final section focuses on activism and advocacy. Supporting alternative media, art and expressionism that represent marginalized groups allows those voices space in our lives. Combining this with protesting unfair systems and engaging in political reform can prevent oppression from escalating into violence.

Even the educational potential of museums is a tool for social change. Today’s greater accessibility of information indicates hope for a brighter future.

“Because of social media, the media [and] the press, people can’t say they don’t know what’s happening in the world the way that many people did not know in the 1940s,” Miller said. “That we might be in a better situation to do what the world could not do for the Jews during the Holocaust—to raise public consciousness, to protest, to effect change.”