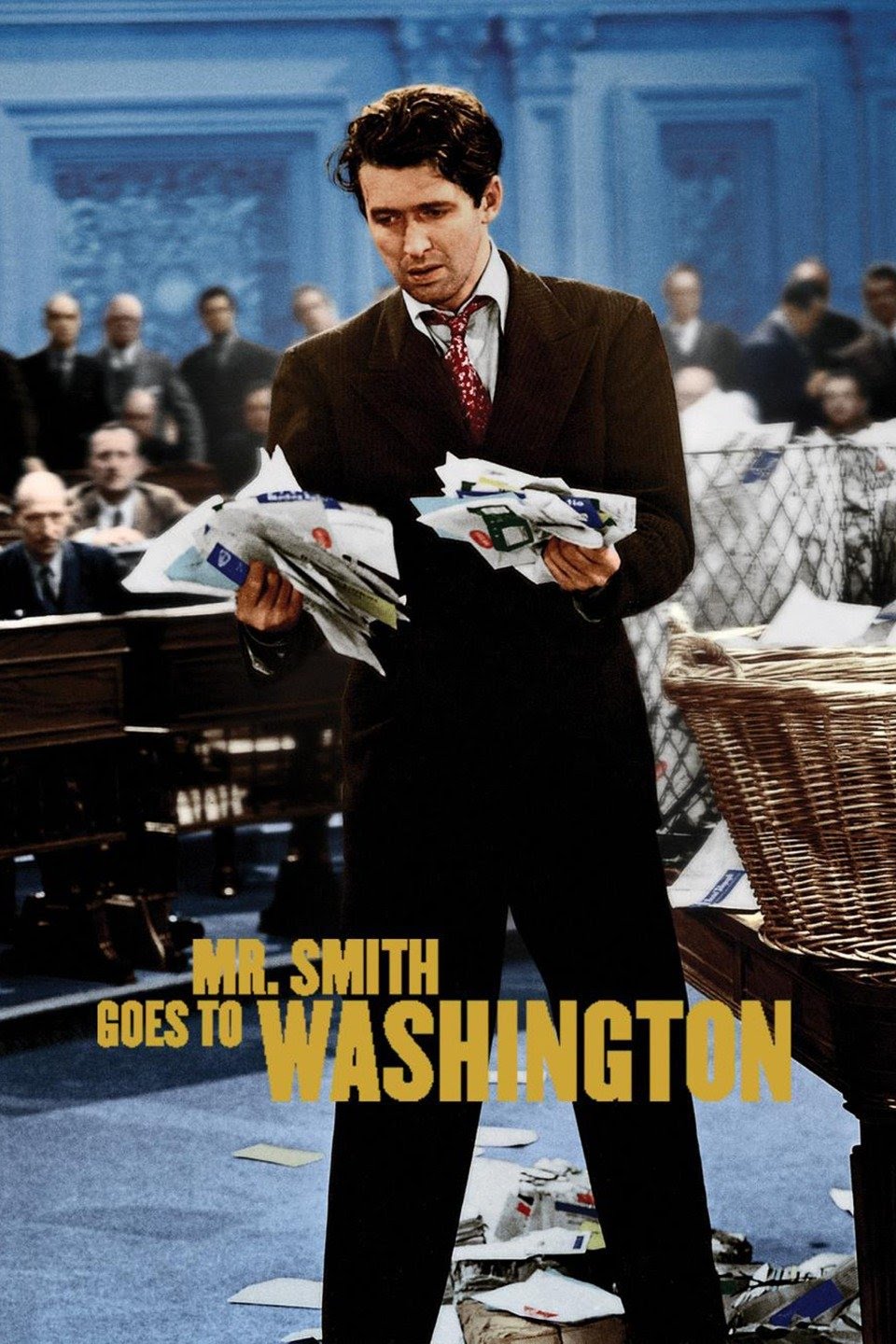

The seminal political film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, directed by Frank Capra in 1939, is one of the greatest representations of parliamentary procedure within the United States Congress, albeit dramatized, and it represents what the filibuster has to do with the overall legislative process.

The film is about newly appointed U.S. Senator Jefferson Smith, who fights against a corrupt political system. The film was somewhat controversial when it was first released, though it was successful at the box office and it made lead James Stewart a major star at the time. It was also loosely based on the life of Montana Senator Burton Wheeler, who underwent a similar experience when he was investigating the Warren Harding administration.

One of the aspects of the movie most intriguing to politicos is Smith’s dramatic filibuster, where he bellows to his fellow politicians about fairness, corruption and democracy. The scene certainly intended to convey an alleged necessity for minority obstruction, a “man of the people” filibuster and democracy’s need for it.

Despite the heroics from Smith, the filibuster doesn’t really work that way. Thanks to continued polarization, the Senate in its current iteration is objectively a failure, having provided very little substantive legislation for the average American citizen in the last 50 years.

The filibuster must be abolished with all speed if any legislation intended to help the people will be passed. The filibuster, as it stands today, is born of white supremacist ideation, creates gridlock in otherwise day-to-day legislation, and increases polarization within government at large.

This was not always necessarily the case.

A brief history

The history of the filibuster as today’s scholars define it began somewhat accidentally in the 1800s, with a rather famous murderer and politician named Aaron Burr.

In 1805, Vice President Aaron Burr laid out a series of suggestions for restructuring congressional rules for the sake of simplicity. One proposition was that both chambers eliminate something called the “previous question” motion, which permitted a simple majority to end the debate on a topic and force a vote. The Senate took Burr’s advice; the House did not.

At the time, neither Burr nor anyone else thought that scrapping the previous question rule would create a 60-vote threshold for passing legislation through the Senate, which was a concept that the Constitution’s framers overtly rejected. In fact, the case for getting rid of the previous question rule was more or less that it was redundant.

“It was a simple housekeeping matter,” wrote Molly Reynolds, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “The Senate was using the motion infrequently and had other motions available to it that did the same thing.”

It took decades until anybody recognized its absence, meaning that any senator could talk about anything they desired, for as long as they wanted; thus, the filibuster was born.

The first known filibuster happened in 1841 over an issue of patronage. The minority Democrats sought to force the majority Whigs to utilize their preferred printers to produce the Congressional Globe, a forerunner to today’s Congressional Record. Months later, a more consequential filibuster arose as Senator John C. Calhoun (D-SC) tried to block the formation of a national bank.

At that point in history, it’s not clear that the filibuster was strictly viewed as necessarily racist by the standards of the time. It is clear, however, that pro-slavery senators such as Calhoun of South Carolina utilized the filibuster to protect southern pro-slavery interests.

What is not especially controversial among scholars is that the current filibuster is inextricably bound up with the Jim Crow era. “It’s been a tool used overwhelmingly by racists,” said Professor Kevin Kruse, a historian of American politics and race relations at Princeton University.

According to a report entitled “The Impact of the Filibuster on Federal Policymaking” created by the Center for American Progress, “from the late 1920s through the 1960s, the filibuster was primarily used by Southern senators to block legislation that would have protected civil rights—anti-lynching bills; bills prohibiting poll taxes; and bills prohibiting discrimination in employment, housing, and voting. These anti-civil rights filibusters were often justified with “inflated rhetoric about an alleged Senate tradition of respecting minority rights and the value of extended debate on issues of great importance.”

In 1917, the Senate resolved to reform the filibuster by adding a provision allowing two-thirds of senators to vote on a “cloture” motion which would end the disruption of an individual senator who just won’t stop talking, according to a Brookings Institute analysis.

This procedural amendment, called Rule 22, was intended to make filibustering more difficult. It had a contradictory effect: it was now probable that a minority of senators could block any bills by voting down cloture motions.

This is how the filibuster works today, albeit now with a “three-fifths threshold for cloture” instead of the original two-thirds after a 1975 reform.

While much of the Senate’s business now involves the filing of cloture motions, there are some significant exemptions. One comprises nominations to executive branch appointments and federal judgeships on which, thanks to two procedural alterations implemented in 2013 and 2017 respectively, only a simple majority is necessary to end debate.

The second involves certain types of legislation for which Congress has previously written into law special procedures that limit the amount of time for debate. Because there is a specified amount of time for debate in these cases, there is no need to use cloture to cut off debate.

Perhaps the best known and most consequential example of these are special budget rules known as the budget reconciliation process, which allow a simple majority to adopt certain bills addressing entitlement spending and revenue provisions, prohibiting a filibuster.

The arguments

For the majority of American history, filibusters were uncommon. There is not an exact count of how many filibusters are actually initiated, partly due to the fact that it is often unclear if one is even being attempted.

Sometimes, the warning is unofficial, even anonymous—an attempt to halt legislation from being considered on the floor at all. The count of the cloture votes, then, is the only way to record how often the majority tries to end a filibuster.

The data on cloture votes indicates two inescapable conclusions: The Senate does not pass as much meaningful legislation as it did 50 years ago and beyond, and that the filibuster is a serious candidate for the most obstructive aspect of legislation in all of Congress.

For instance, according to a report from the Brennan Center for Justice, “from 1917 to 1970, the Senate took 49 votes to break filibusters. Total. That is fewer than one each year. Since 2010, it has taken, on average, more than 80 votes each year to end filibusters,”

Furthermore, the cloture process consumes more than 30 hours of Senate floor time, according to the U.S. Senate’s official website.

Even if a cloture vote is successful—which they often are not— the simple act of voting to stop constant filibusters freezes the majority from producing legislation action of import. The minority hijacks the majority’s time, even if the vote eventually passes unanimously. It’s an act of artifice and immaturity that minority parties use to ensure less gets done.

In the 2019–20 Congressional schedule, there were more than 260 cloture votes taken—a new record, according to the Senate’s own data.

The filibuster has transformed the Senate from an institution that requires a majority into one that requires an increasingly rare supermajority, making any kind of real action near impossible.

Defenders of the filibuster insist the Senate is intended to be a “cooling saucer,” insulating the passage of bills from the passions and vagaries of the moment.

This is true about the institution as a whole. That’s why each state receives equal representation, making the Senate the most undemocratic legislative chamber in any advanced democracy on earth.

It’s why senators were originally chosen by state legislatures, not directly by voters. It’s why Senate elections are staggered, with only a third of the body facing the voting public in any given cycle.

That’s why senators serve six-year terms—four years longer than members of the House, and two years longer than the president. It also means that they can receive lower poll ratings than their House or executive compatriots, and still remain in office.

Even the (sadly ironic) debate that the filibuster protects minorities has racist and unfair undertones, considering the history of what the “minority” really is in terms of the legislative process.

Throughout the 20th century, the filibuster was chiefly utilized to protect the tyranny of the majority over the minority. Filibusters were rare in the midcentury Senate, but when they happened, it was primarily for one purpose: making it easy to preserve racial subjugation in the South and throughout the country.

The framers never wanted a supermajority. Take Alexander Hamilton’s “Federalist 22,” where he displayed less than subtle disdain for the need of 60 votes in the Senate:

“The necessity of unanimity in public bodies, or of something approaching towards it, has been founded upon a supposition that it would contribute to security. Its real operation is to embarrass the administration, to destroy the energy of government and to substitute the pleasure, caprice or artifices of an insignificant, turbulent or corrupt junta, to the regular deliberations and decisions of a respectable majority.”

The filibuster is nowhere in the Constitution, and it has nothing to do with producing effective legislation. In our current system, one could argue that the filibuster in fact imbalances the notion of a three-institution government. For instance, with no legislation being passed, pressure is placed upon the president and the executive branch to stretch the power of things like executive orders. The judicial branch then declares these actions unconstitutional, all the while citizens suffer.

The Founding Fathers, with all their flaws, did at least envision a deliberative government capable of effective and productive competition among institutions, and a true system of checks and balances, not the mutant form of bicameralism present today. The filibuster has no place in American governance. It is the enemy of all legislation intended to help the people and protect those who need it most.