Portland native Mitchell S. Jackson’s first book has created quite a stir and not just in Portland, but nationwide. The Residue Years was a finalist for many reputable awards including the Pen/Hemingway award, and has been hailed by magazines and newspapers across the country.

Jackson’s past, and the steps he took to get to where he is today, is just as exciting a story as his novel, which is semi-autobiographical and inspired by his own life.

Jackson spent years illegally making money on the streets and doing what he had to get by. After prison, Jackson went on to receive his M.A. in writing from PSU, and his M.F.A. in creative writing at New York University, where he now teaches.

Jackson’s writers dearth was a subject he spoke of at a recent lecture in Portland. How he had not spent as much time as some other writers to read and learn from authors of the past. But also that he has a different kind of education that he has learned on the streets, of which gives his work a unique vitality.

The book begins with Champ imagining his mother’s day before she comes to visit him in prison. He imagines her seeing his ex-wife and picking up his three year old daughter. They buy gifts, his mother talking him up all the while, and then the cold interaction with prison guards.

It is revealing and yet it is a fantasy, which Jackson brings back to reality by saying “Hold the fuck up! This ain’t what happens. Enough with this fantasyland shit.”

From the first sentence his voice is overwhelmingly present. It only takes a few pages to realize that it will be the voice that keeps the pages turning, and makes this story feel so truthful.

The book is written conversationally, with unique colloquialisms such as ishityounot and completely without quotations on dialogue. It all comes together like your friend telling you a story about something that happened yesterday. It is a mix of everyday language and a literary work.

The chapters fluctuates back and forth between a character based on Jackson, Champ, and one based on his mother, Grace.

Jackson’s telling of these two characters with such a close relationship to one another, is where the book finds its spirit and style. As they meander in and out of each other’s perspectives, and how they describe each other’s respective personalities, is where Jackson’s story seem truly unique.

Of his writing from a woman’s perspective—and his mother no less—he was wary at first, but with revision and time he got better. He said it would have been a lie to say this was only Champ’s story, and not at least half Grace’s, if not more so.

The story follows Grace’s attempts to hold her family together after she gets out of rehab, and her eldest son Champ’s efforts to help her, and to build his own family, through whatever means he can…selling crack.

The Residue Years takes place primarily in Northeast Portland, before gentrification took over. So reading the book there is constantly reference to places that you have likely been to or can go to now.

The Portland that Jackson describes is much different than we see now while grabbing a Salt and Straw ice cream cone during the Alberta Street Fair. There are Bloods and Crips, drug deals, a lot of hoop, mainstays at the neighborhood barbershop, and far fewer white people than there is today.

Jackson does tackle gentrification in the book as well. In the barbershop they argue over property values moving up and blacks moving out, and in general the book takes place as gentrification is beginning in the area, around the 1990’s, so the change is present throughout the community.

“It’s nice to walk down Alberta and feel safe, but it really hurts me to see people displaced,” Jackson said during a lecture, of the area today.

The Residue Years was selected as the 2015 Everybody Reads book for various public libraries including our Multnomah County system.

Jackson now sits with the likes of Ray Bradbury, Khaled Hosseini, Earnest Gaines and Sherman Alexi, who have all had books chosen for the program.

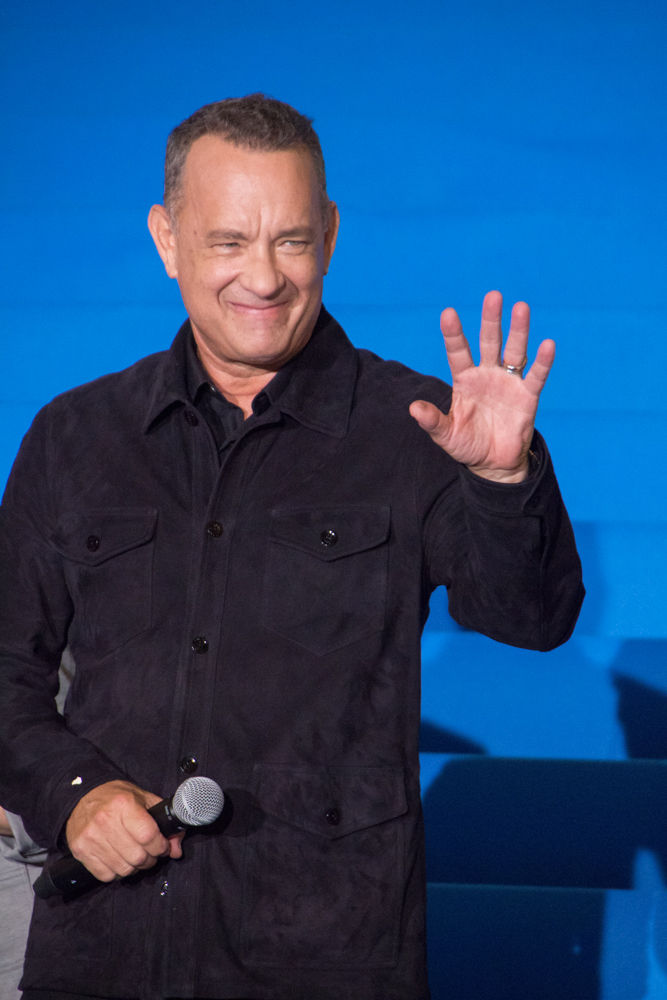

The culmination of Everybody Reads for Mr. Jackson was on March 10, when he lectured at the Arlene Schnitzer theater in Portland, as a guest of Portland Literary Arts Inc.

He began his lecture with a long list of thank you’s. From friend and family, to teachers and coaches, to a friend who did eight years in prison for his drugs. Jackson went on to thank people who had pulled guns on him and not fired, and the cops who arrested him who, again, did not shoot when they could have and the judge who went easy on him and gave him 16 months instead of 10 years.

The focus of his speech was revision, a tool to be used in one’s writing and one’s life. He defined it as the ability to see the work as a whole—a work in progress. To be able to see what is right, and make it more right.