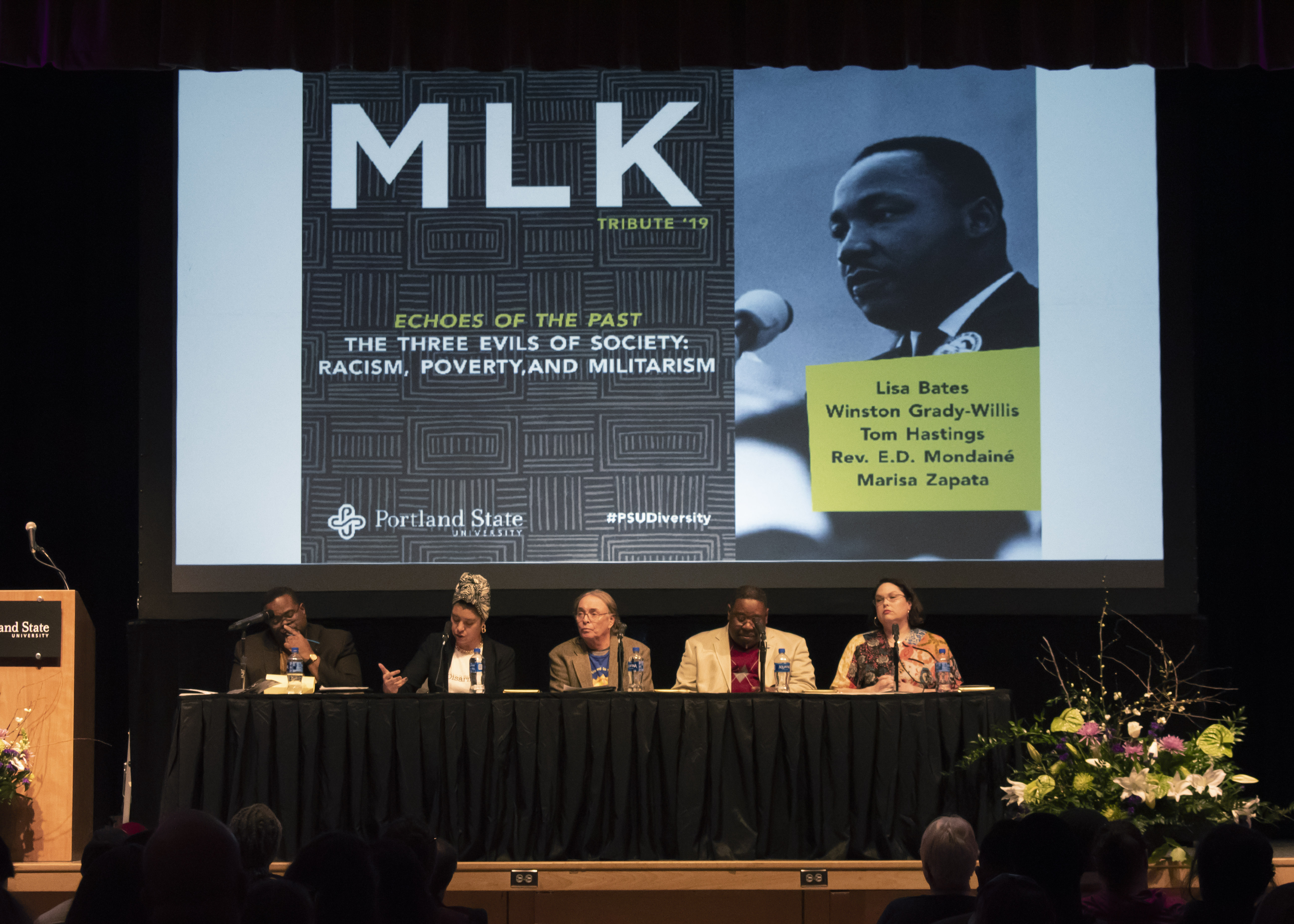

Fifty years after the assassination of civil rights icon Martin Luther King, Jr., a panel of scholars and activists gathered on Jan. 29 in Smith Memorial Student Union to honor his legacy and address contemporary political and social issues through the lens of a speech he gave a year before his death.

“For so long we have been looking at the most neutered, the most anodyne clips of Dr. King’s thinking,” said Lisa Bates, assistant professor at Portland State’s Toulan School of Urban Studies & Planning. “Here we’re really able to engage with his diagnosis of the origins, the causes and the intertwined nature of racism, economic exploitation and militarism.”

In 1967, as protests against the Vietnam War proliferated, King delivered his “‘Three Evils of Society” address at a political conference in Chicago. The speech identified racism, poverty and militarism as the three gravest challenges facing contemporary United States society.

“This particular remembrance speaks eerily to present day experience and looks strikingly similar to present day worldview,” said Reverend E.D. Mondainé, President of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Portland chapter.

On Campus Police

Moderator Winston Grady-Willis, director of the PSU School of Gender, Race, and Nations, preceded the panel discussion by connecting the event to the death of Jason Washington by PSU campus police officers in June 2018.

“Many of us have been involved in DisarmPSU activities, and many of us have been in dialogue with individuals on campus who don’t take that position,” Grady-Willis said. “We respect and lift up academic freedom.”

“Re-reading the speech, I was struck by how much what Dr. King has said about racism and poverty seem like they were words written last week,” said Marisa Zapata, director of Portland State’s Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative.

Disarming sworn campus police is among the questions being considered during an external review of PSU campus public safety policies by the firm Margolis Healy, whose final report has yet to be released.

War and poverty

“To me, homelessness is the clearest example of societal failure,” Zapata said. Her research has identified an “implicit and explicit bias in shelter workers,” with people of color more likely to be disciplined in homeless shelters and more likely to be asked to leave for the same infractions as someone who is white might commit.

One aspect of the speech Zapata said was more difficult to relate to concerned King’s criticism of the Vietnam War, a stance that was so controversial at the time it earned condemnation from civil rights leaders and resulted in the severance of a formal working relationship with President Lyndon B. Johnson.

“There are a lot of ways in which how we think about and talk about war has changed since 1967,” Zapata said, “Ways that are deeply terrifying and interconnected.”

Congress hasn’t officially declared war since World War II. Since then, presidential war powers have expanded armed conflicts. According to the Congressional Research Service, it’s not clear whether a president requires Congressional authorization at all.

Zapata also characterized the war on drugs, war on terror and recent border security actions as examples of campaigns targeting communities of color within U.S. borders. “Our wars are not just external; they’re internal.”

Communities of color

Challenges to political unity within marginalized groups and communities of color were also featured during the panel discussion.

In response to comments from Mondainé about “Black conservatism on immigration” and “being tired of being melted into the pot that says we’re communities of color,” Grady-Willis proposed a balancing of Black self-determination against “[Having] an expansive view not only of our current reality, but also of our history, that may force us to look at some issues a bit more uncomfortably.”

“We often talk about the nature of enslavement in the so-called New World and the experiences of enslaved Africans, and that’s absolutely true,” Grady-Willis continued. “But it’s only been recently that there’s now been more of a substantive discussion of the fact that our indigenous brothers and sisters have also been enslaved, and for hundreds of years.”

Grady-Willis also highlighted the case of Buffalo Soldiers, Black soldiers who served in the U.S. army from the Civil War to the mid-20th century. While Buffalo Soldiers should be celebrated for their role as Black soldiers who helped win their own freedom in the Civil War, he said, “What we often tend to try to sanitize or have euphemism around is the fact that those very same Black U.S. soldiers were often on the front lines of the genocide of indigenous communities throughout the U.S. West.”

“We have spent many hundreds of years in an oppressive structure that pits people against one another in incredibly complicated ways,” Bates said.

According to the panelists, student and youth activism will play an important role in the future of social justice movements.

“How can we support our students?” Bates asked. “How can we support our future students, these teens who are around our city asserting their full humanity and who are envisioning a future in which they’re learning and working and where their creative pursuits are truly valued?”

“I think the way we need to [do that] is to continue to talk openly about the ongoing failures in our institutions and organizations,” Bates continued. “We need to hold on to these echoes of the past that continue to cascade around us.”