A lot has changed in the 13 years since Irrational Games’s BioShock released.

BioShock was seen by many to be a huge leap forward in narrative-driven games in the industry. It was a game that was ahead of the pack by a large margin, striving to resurrect the design of early 90s PC games like System Shock while maintaining their heavily politicized stories. Ken Levine, the game’s creative lead, directly cites the works of Ayn Rand and George Orwell as fundamental inspirations for the story. It takes place in an underwater city built on the foundation of objectivism—a society full of the world’s greatest thinkers, detached from the shackles of modern politics that restrict progress and creative cultivation. It’s a city where a man can be his own hero, writing his chapter in the history book, and it is a city doomed to fail, as the separation of politics and control leads to disarray and violence.

BioShock, much like its predecessors such as Deus Ex, wasn’t afraid to be political. It wasn’t afraid to get its feet muddy and delve into a territory that the gaming industry hadn’t entirely dared to explore. Its 2013 follow-up BioShock: Infinite was similar, telling a tale of a nationalistic, nostalgic flying city rooted within the ideals of white supremacy and elitism, oppressing the working class in a rose-tinted world painted with bloodshed. In many ways, the BioShock games struck a particular chord that many games in the following 13 years have failed to replicate or even attempt.

Flashing forward to 2019, the industry saw the release of the latest Call of Duty title, taglined Modern Warfare. However, unlike Ken Levine, its creative leads completely denied the presence of political themes. A game that features no-knock raids isn’t political. A game that features terrorist attacks and civilian casualties isn’t political. A game that presents an unforgiving, glorified portrayal of war through chemical weapons, torture and POWs isn’t political. By definition, war is political. The refusal to acknowledge those themes as political is deafening, irresponsible and dangerous.

The presence of apoliticism in marketing as well as writing within the entertainment sphere isn’t new. For a long time, the film industry has insisted films with blunt political themes aren’t political, and their fans do the same. Most of this has to do with the complete misunderstanding of politics—look at the comments of any article that expresses a political opinion or analysis of any blockbuster movie or game, and you’ll find many people directing their political opinions towards representation and diversity rather than…politics.

Black Panther isn’t a political movie because of its plot, which revolves around monarchy and monopolizing natural resources. No, it’s a political movie because it’s one of the only major blockbuster films of the last 10 years to feature a black protagonist. The Last of Us: Part II isn’t political because it takes an introspective, critical look at violence and revenge; rather, it’s political because it has a multicultural cast of characters and a lesbian lead. These distorted, warped views of politics are more indictative of cultural bias and discrimination towards marginalized groups than they are of real, political themes.

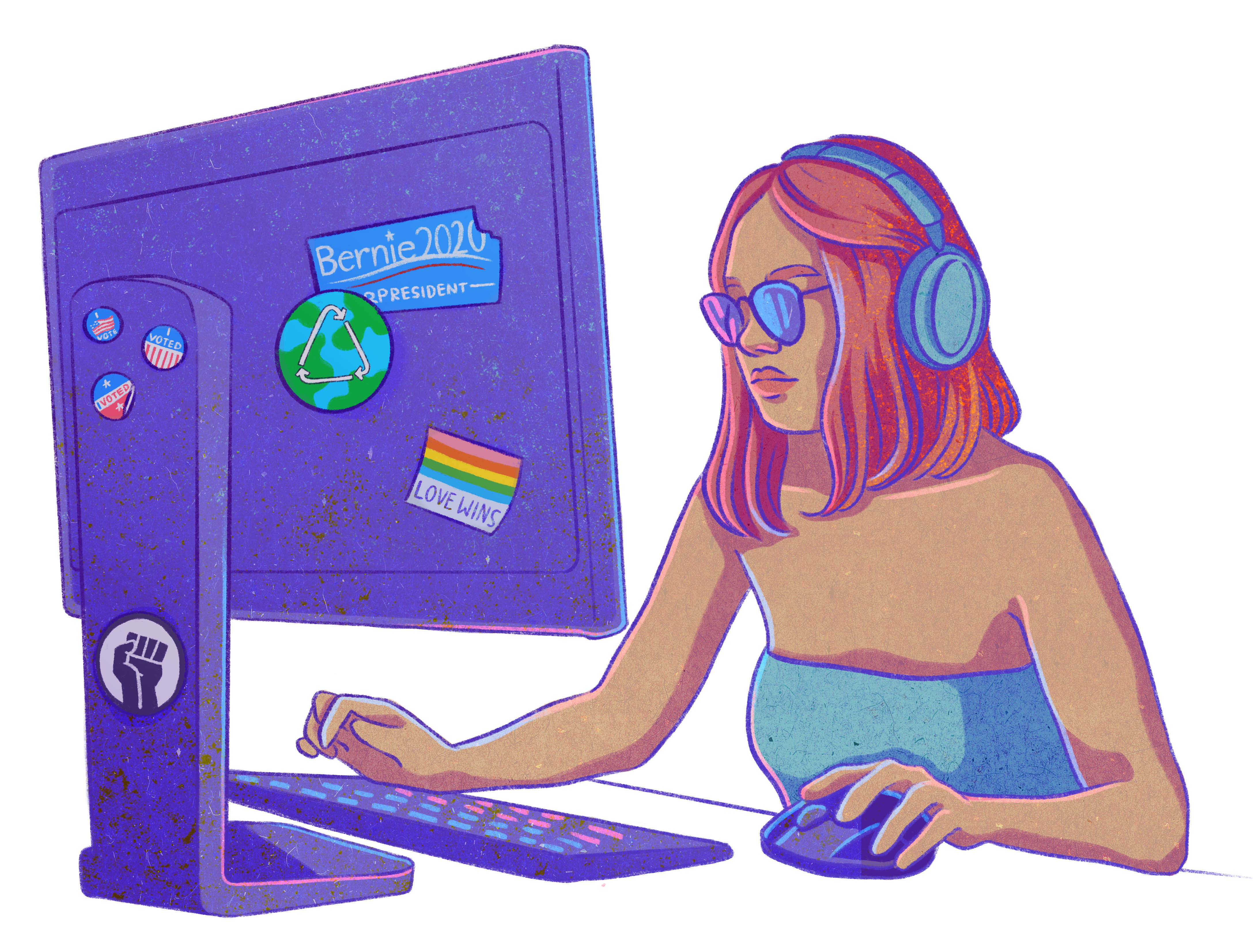

The vehement hatred displayed towards the presence of politics in entertainment by internet commentators is what causes billion-dollar marketing teams to shy away from politicism in marketing. To call Modern Warfare a political game would be to ostracize a large chunk of fans of a series that gained notoriety for hosting a player base filled with hate speech and toxicity. To market anything as political nowadays is to walk around eggshells. Indeed, a game like 2017’s Wolfenstein: the New Colossus received extensive backlash for its marketing tagline of “No More Nazis.” Wolfenstein, a series that, for 20 years, has been solely about reclaiming a fascist, alternate-universe America from Nazi occupation. A series that has only ever been about wiping Nazism off the face of the planet. Yet, many complained that the series had become “so political.”

Perspective is a common theme among people who complain about politics—notably, that of “multiple perspectives.” Many believe aligning a creative vision with one political ideology is dangerous or even discriminatory. Many responded to “No More Nazis” with cries of “don’t shame others’ beliefs!” Besides apolitical marketing, many creators have shifted towards views that refuse to make any concrete point. Captain America: Civil War’s story is one of politics, and, notably, control of justice. Yet, by the end of its two-hour runtime, it never resolves the two clashing beliefs at the focus of its plot. The political backdrop is merely a facade, an excuse to showcase 147 minutes of spandex-dressed heroes punching each other.

People are afraid of being told what to believe, and, as such, choose to consume the most apolitical, and therefore artistically lobotomized, entertainment that they can get their hands on. A complete refusal toward and denial of political media is far more dangerous than the exhibition of a singular ideology. Any criticism of a consumers’ beliefs is seen as a personal attack on them. Several decades later, many still insist that fictional sci-fi villains such as the Daleks of Doctor Who or the Empire of Star Wars are not based off of the Nazi regime of World War II, despite the obvious phrases such as “master race” and “stormtroopers” lifted directly from history.

As art is produced from the most carnal, primal and personal thoughts of the artist’s mind, it is, inherently, political. There will always be scraps and remnants of a creator’s personal ideology and politics lurking in the dark of their creations, because those ideologies dictate our way of life and permeate throughout every essence of our being. Regardless of what Modern Warfare’s leads say, their game is, in fact, political. Their personal biases are evident—the historical erasure of the United State’s involvement in the Highway of Death on the outskirts of Kuwait City in the game’s plot is proof of this. The glorification of war crimes and violence committed on sovereign soil and the excusal of said violence is dangerous, irresponsible and manipulative. To erase politics from art is no different than to erase tragedy from history.

Entertainment needs to reclaim politics. Creators need to insist creative control and emphasize the political themes of their work. Entertainment is a product, but that doesn’t mean marketing teams should sacrifice the integrity and honesty of their work to appeal to consumers. In a generation filled with consumption, what we watch, play, read and listen to influences our opinions and perspectives more so than ever. An onslaught of apolitical, neutral pieces of media does nothing to make us think. Rather, it diminishes our perception and critical understanding of art, politics and the world we live in. The recent, real-world events surrounding police brutality and protests have influenced the entertainment world in a deep way. Many people are realizing the consequences of the masked protector superhero archetype or the endorsement of guns and violent justice in action movies as a byproduct of the last two months in national news.

Confronting politics and encouraging them leads to a more truthful depiction of a creator’s vision, and leads to more impactful, emotional pieces of art. I can’t remember the last time a cookie-cutter blockbuster made me feel any emotion other than a dopamine rush, but it would take more than a few hands for me to count the number of unabashedly political films I watched last year that elicited a strong emotional reaction out of me. Neutrality is the death of art and encouraging it will only cause no progress within either the artistic world, or the world we live in.