It was kind of a lucky break for Nintendo to release Animal Crossing: New Horizons when it did. With COVID-19 raging and the world succumbing to a decided lack of things to be saccharine about, the Nintendo Switch game and latest entry into the Animal Crossing series seems to have struck a chord. Intended as an escape from the world and its woes, ACNH is instead an unsophisticated debt simulator.

The argument can be made that the terms of your indebtedness mean essentially free money, but the need to constantly upgrade and improve your island in order to unlock new features and expand existing ones is a perverse incentive toward peonage. You are constantly under a new mechanic of debt, from house expansion fees to basic infrastructure costs that are borne strictly by you. Unlike other games where pay to play is optional, in New Horizons you are always under the thumb of the Nook cartel.

To varying extents, people are made to do tasks using their own time in order to finance essentially every facet of life on their island: pull weeds, dig up fossils, catch fish, then sell these to members of the Nook family in order to pay off debts owned by the Nook family. The extensive ways in which you are made to do actual and substantive work in order to promote an economy of debt amount to what can be considered an elaborate life simulator, but with more running from tarantulas.

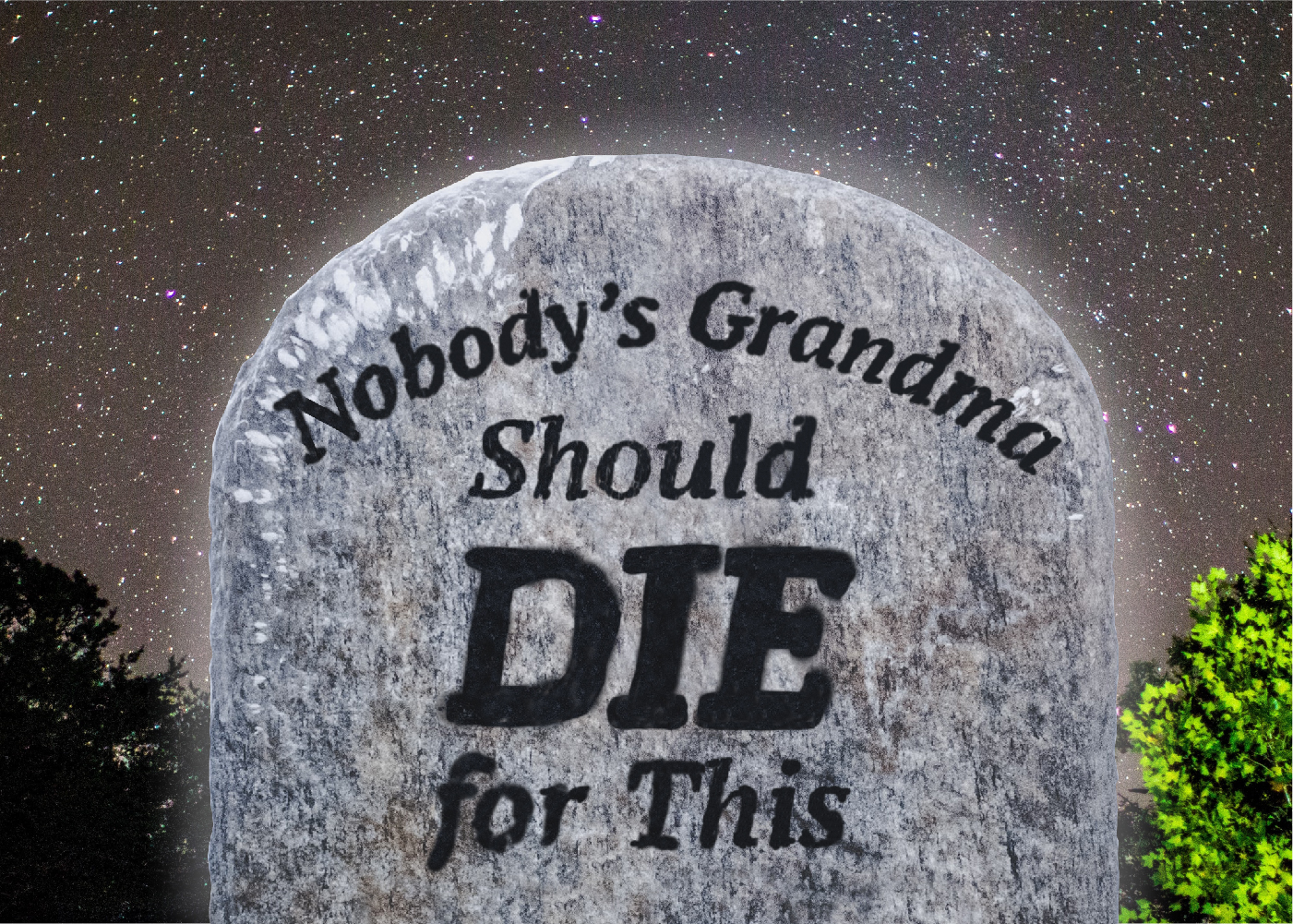

Or, I dunno, you might be running from tarantulas every day already.

Either way, Nintendo has successfully gamified the millennial and Generation Z trend of “adulting,” a twee way to reframe the capitalist workaday for the TikTok views. Everything is a random number generator fight for newness and notability, even the act of shaking trees. It’s mind-boggling most are incapable of connecting the act of shaking trees every day because that’s how you acquire new furniture or funds to the essential nature of labor and work; no need to read Marx to see how this is alienating to the people toiling away at a digital furniture farm, no need to refer back to Upton Sinclair to see how subjecting them to virtual wasp stings is a twisted way to establish a risk-for-reward mechanic in the basic act of laboring.

And yet, this is a really fun game and a fantastic way to while away the time during this pandemic.

Perhaps it’s because it re-establishes routine and social networking that it is such a popular game. Yes, it’s true the economic system that underpins the game and its mechanics are onerous and in some ways abusive, but ultimately, it’s a low-threshold access point for people seeking out a life of toil that is actually cute and enjoyable. This is the height of escapism inherent to video games; it mirrors the life we are escaping, but it’s more colorful, rewards are more frequent and far more conspicuous and it gives you a chance to apply your personal life to a social structure that rewards risk-taking in establishing working relationships.

Tom Nook might be the capitalist overlord maintaining his power through consolidation of earning and self-support into his fuzzy little fists, but he’s a cute overlord and that’s what matters most. Nook is an expert at manipulating the conditions to ensure he’s both benefactor and distributor of the common wealth, a master of benefice that leads you into a sophisticated labor compact. This is why he is perhaps akin to a dungeon master or game master in tabletop gaming. He is a psychopomp and initiator of your world’s cycles. He’s like a chubby Gary Gygax in a floral print shirt.

The other characters that populate your island all seem to have some financial tie to either Nook or the labor regime that he established. You are often tasked with the same labor that sustains you daily in order to participate in whatever scheme these characters have hatched up, from bug collecting to fishing. The limited economy is not expanded by these outsiders, nor are you provided with a novel form of your existing labor. Tom Nook’s established society is thus contingent upon the manner in which he sets you upon certain tasks, so there are no cooking exercises, just more fishing and tree-shaking. You aren’t crafting your own home, just paying your bells toward expansion. New Horizons is simplicity in design and complicity in capitalism.

Animal Crossing: New Horizons is thus an amazing game and a horrifying trap at the same time. The escapism suggested by the game’s nature is undermined by the routines required to play, the whimsy plastered with price tags. Isn’t that what we want, though? Normal? If the labor-spend-labor dynamic of our life is disrupted, then it stands to reason that something that approximates normal will be popular; add a cotton-candy veneer to this stand-in world and you have a winner.

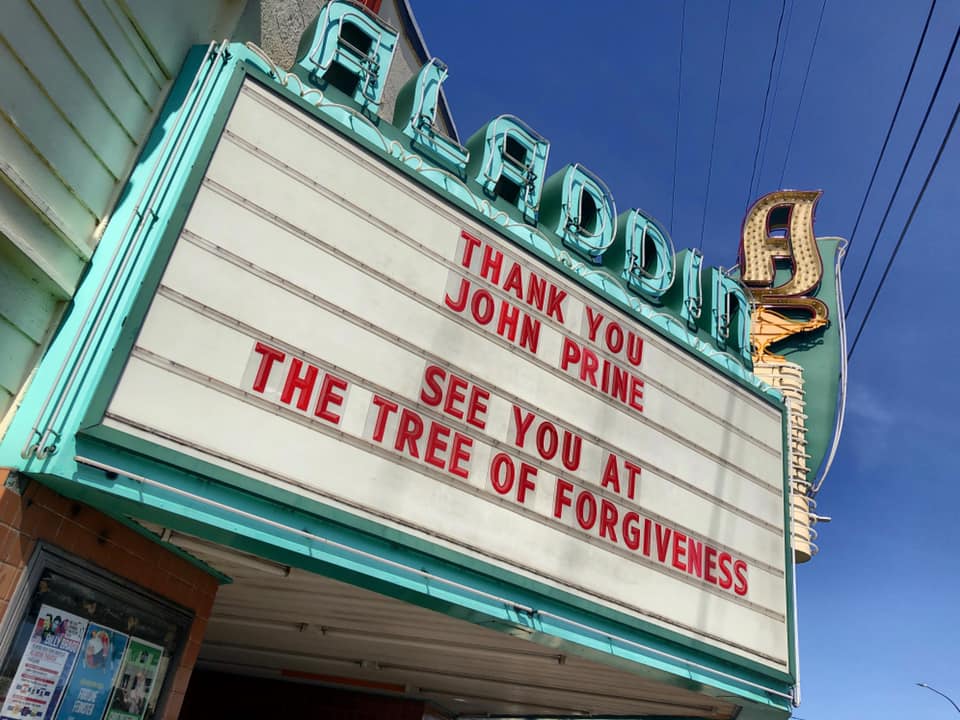

See you in paradise.