Although three months have passed since John Prine died of COVID-19 on April 7, the pandemic has only gotten worse. Prine’s work frequently grappled with loneliness and isolation, and his words, specifically on his 2000s album Souvenirs, can be a comfort in the chaos of the ongoing pandemic that took his life.

At age 54, still recovering from radiation treatment to fight cancer in his neck, Prine recorded his album Souvenirs. A relatively modest reworking of 15 of Prine’s early songs, the album was designed to give Prine “master recordings” of his songs to release in several European countries, such as Germany, because he “always wanted to be popular there,” according to the liner notes.

After finishing and mastering the record, Prine and his label decided to release it in the United States, as he “would like to be popular there as well.” The album was received well by Prine’s longtime fans, but earned little critical recognition. One reviewer wrote “the new versions rarely surpass the originals.”

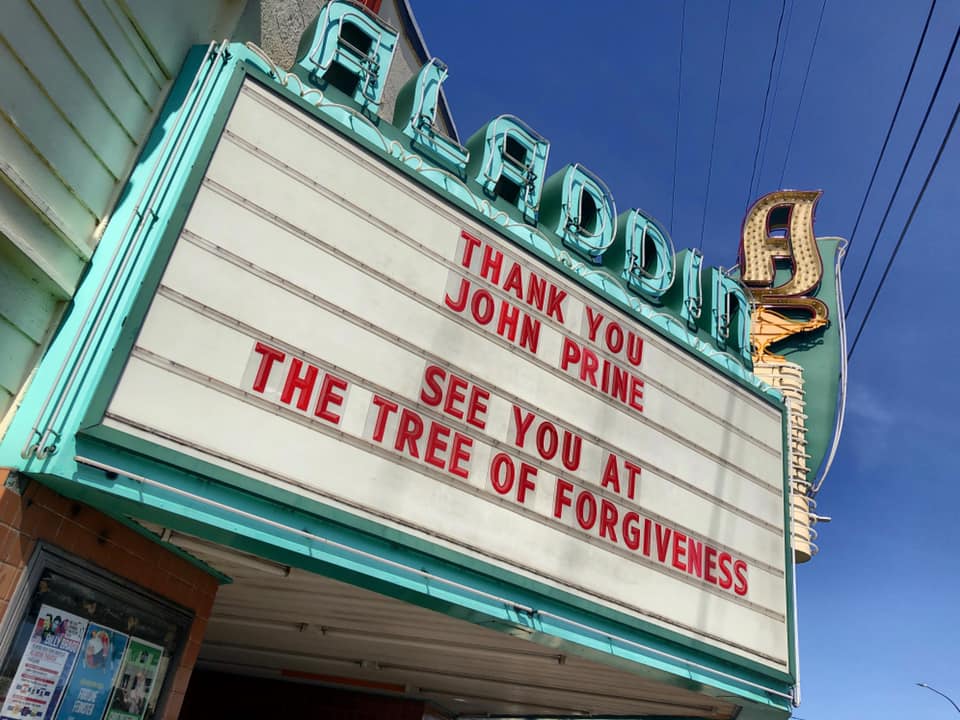

But that was before Prine passed away on April 7, at the early height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. Prine was one of the first and most notable artists to die of the coronavirus. His 50-year songwriting career has drawn compliments from Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Roger Ebert, Roger Waters, Kacey Musgraves, Kurt Vile and many others.

Equal parts cheeky and melancholy, Prine was the master of finding beauty in the macabre. Though his ashes have been spread across the Green River in Kentucky for three months now, his words remain ideal for guiding us through the experiences of the ongoing pandemic, and help to reckon with his own death. And Souvenirs provides a smooth entryway into Prine’s career and his charm.

The album contains some of Prine’s most poignant lines, delivered in the raspy baritone that Prine earned as a result of his cancer treatment. The new voice, partnered with stripped-back acoustic guitar and minimal studio adjustments, changes the effect of Prine’s classic songs, as on the chorus of the titular “Souvenirs,” when Prine sings, “Well it took me years / To get those souvenirs / And I don’t know how they slipped away from me.” On the original recording. it plays as a sheepish admission, but in Prine’s re-recording the line reverberates, ending in a more somber place.

The album features Prine’s most well-known and covered song, “Angel from Montgomery,” a southern ballad about a woman in a stifling relationship. On recent relistens, lines such as “There’s flies in the kitchen / I can hear ’em, they’re buzzing / And I ain’t done nothing since I woke up today” resonate. The stupor of quarantine feels reminiscent of the muggy Alabama hopelessness that the song captures in the refrain, “To believe in this living is just a hard way to go.” The re-recording features a sparse electric guitar solo, moving in step with the pain and joy of Prine’s lyricism.

Many of the tracks on Souvenirs were originally recorded for Prine’s self-titled first album, released in 1972. The album was Prine’s breakout, receiving widespread critical and commercial acclaim. A reviewer for Rolling Stone at the time wrote “Good songwriters are on the rise, but John Prine is differently good.” In total, six tracks off of John Prine made their way onto Souvenirs, reflecting the massive impact Prine’s debut album had on his career. Unlike Bob Dylan or Van Morrison, whose early albums don’t reflect the forms their works would come to take, Prine’s first album may be his most iconic.

On an overall stripped-back and reserved album, the ballad “Donald and Lydia” stands out as one of the most bare tracks on Souvenirs. Originally featured on Prine’s debut album with swaying slide guitar and band backing, the re-recorded tune features mostly just Prine’s fingerpicking guitar and stark voice. The song depicts a romance between two lonely individuals, a “fat girl daughter” and a reserved private first class. The two spend the ballad apart, dreaming of romantic scenes and happy endings. The song ends saying that they “made love from ten miles away,” suggesting the romance had been nothing more than a figment of their imaginations.

The reason so many of Prine’s lyrics seem to tug at current feelings of isolation, loneliness and longing is simple. Good songwriting is universal. Whether Prine wrote from the perspective of a lonely housewife, a Biblical character, a heroin addict’s child or himself, his careful use of tone and folk-isms landed a gut feeling every time. As we struggle to understand a pandemic that’s seemingly endless, listening to the quiet struggles of the characters in John Prine’s songs is a reminder that human experience didn’t begin in March, and that the way we feel now isn’t something uncategorizable. It’s just human.