This review contains spoilers for WandaVision.

WandaVision is a show unlike anything else in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. In a world full of CGI superhero fights and infuriatingly quippy dialogue, WandaVision took a chance to do something unique: explore the effects of grief, with rich, emotive characters. Ultimately, however, the show fell back on the same, tired MCU tropes that have plagued the rest of the multimedia behemoth’s creations. WandaVision worked until it didn’t. But somewhere in the aftermath of the finale, we can find a few nuggets of inspiration that Marvel will hopefully develop moving forward.

WandaVision begins in the immediate aftermath of Avengers: Endgame, after the world-annihilating snap has been reversed and everyone dusted by Thanos has returned to life. This aspect of the show is immediately intriguing; MCU releases have only recently begun to touch on the snap and the world’s reaction to it in greater detail. One person who didn’t come back, though, is Vision, Wanda Maximoff’s love interest. Vision, if you recall from Avengers: Infinity War, was killed after Thanos forcibly ripped the Mind Stone from his head.

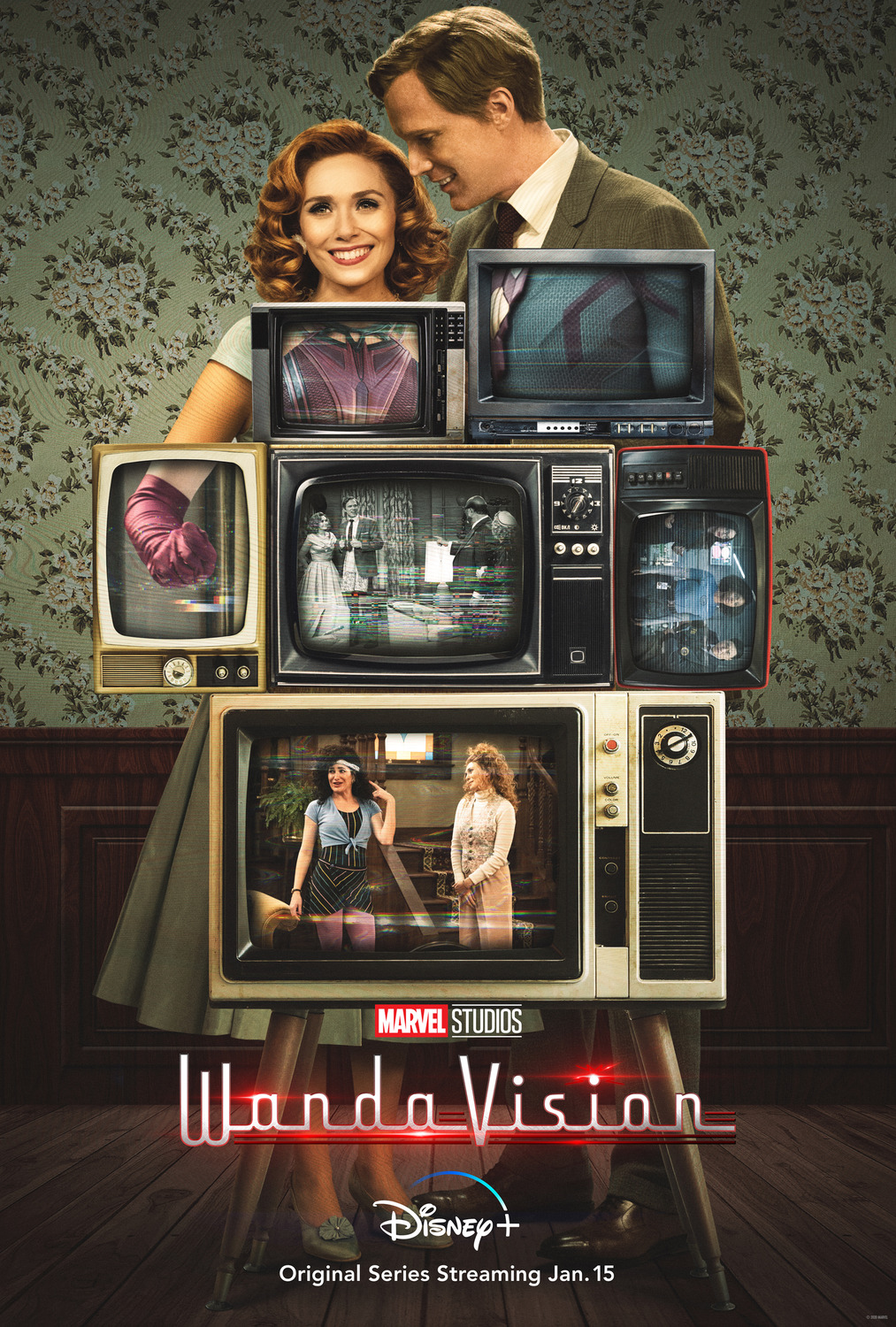

We begin WandaVision in a confused state of limbo: isn’t Vision supposed to be dead? How is he alive in the show? The first few episodes of WandaVision take place entirely inside a retro TV universe, spoofing programs like I Love Lucy and The Dick Van Dyke Show. Wanda and Vision have an idyllic suburban existence in TV land, as we watch their lives play out like an audience gazing upon a black-and-white vintage television.

It is eventually revealed that this TV universe is a coping mechanism for Wanda, who created a pocket dimension for herself in an idealized suburbia complete with a cast of supporting characters and her very own co-star, played by a manufactured clone of Vision made of “the piece of the Mind Stone that lives in [her].” Wanda, after failing to recover Vision’s body from a government facility, invents a world where he is still alive to avoid confronting her own grief. This is captivating storytelling that you don’t usually encounter in the MCU. WandaVision’s plot felt more like a storyline out of the comics than their candy-coated film counterparts.

But then WandaVision hits a roadblock. The first few episodes of the show are incredibly unique by Marvel standards, showing us Wanda and Vision’s life entirely within an in-universe TV show. But by episode four, we’re introduced to characters in the “real world,” agents of the government agency S.W.O.R.D. attempting to break into Wanda’s pocket dimension. We discover that the town of Westview, the setting of Wanda’s TV show, is a real town that was somehow taken over by Wanda’s magic. The force field surrounding Westview is shaped like a hexagon, which the characters on the outside call the “hex”—clever.

I’m not necessarily opposed to this conceit. Of course, the outside world would react to the takeover of Westview, and the government would want to get to the bottom of it. My problem is how these characters change the tone of the show. Inside Westview, the tone of the miniseries is completely different from any other Marvel endeavor. Everyone talks like mid-century sitcom characters, its visual language is distinct—the older sitcom sections are shot in a 4:3 aspect ratio—and there’s a thick layer of dramatic irony coating every scene. The real world characters, in contrast, sound like, well, Marvel characters. The dialogue goes back to the same quippy back-and-forths we all know; everything is some shade of blue, orange or grey; the show, simply put, reverts to the same old shit.

And that’s really the fundamental problem with WandaVision. Skipping ahead to the finale, we discover Wanda’s neighbor Agnes was actually a powerful witch named Agatha Harkness, seeking to learn the secrets of Wanda’s magic and steal it for herself. We also discover S.W.O.R.D. has rebuilt Vision’s body into a weapon whose only goal is to kill the illusory Vision inside the hex. So how does WandaVision deal with Wanda discovering the true extent of her powers, or the possibility of losing Vision for a second time?

This is a Marvel show. It is obviously resolved with a CGI Dragon Ball-style superhero fight.

After building up the emotional stakes for a whole season, WandaVision ends with yet another climactic fight scene wherein a bunch of superpowered heroes fly in the air and shoot each other with energy beams. I have nothing against a good fight scene—but WandaVision, of all shows, really did not need one. Like Karen Han wrote in her review in Slate, “The emotional complexity that made the show so engaging wasn’t completely obscured, but it was hard to find amid the sea of red, purple, and blue laser beams that flew around the screen.”

In the end, Wanda defeats Agatha and Wanda Vision defeats evil Vision. The fight between Wanda and Agatha is pretty unremarkable. It’s cool that evil Vision is defeated through a philosophical discussion about the Ship of Theseus and the nature of consciousness—a real bat-signal moment for bro intellectuals.

The emotional core of WandaVision was Wanda’s experience with grief at the loss of her husband. Now that we know Vision is alive again, albeit in an altered state, what exactly was the point of this series? Initially, WandaVision had the courage to deal with complex emotional issues, and at the end it ran away from them. Let’s hope future Marvel releases take a cue from WandaVision’s premise, and take a chance to explore difficult, adult themes with the sensitivity and nuance they deserve.