The United States is one of a small handful of countries with no official language. While it may be tempting to interpret this as intentional homage to the diversity of languages and cultures that make up this nation, the reality of the American attitude towards second language acquisition tells another story.

According to a report by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, only 10% of Americans speak a language other than English proficiently. Of that 10%, three quarters are heritage speakers, having learned the language at home.

While learning a second and even third language is common practice starting in primary school in many regions of the world, only 11 U.S. states mandate a foreign language requirement at the secondary level, according to American Councils.

Many post-secondary institutions offer opportunities for students to study languages previously unavailable to them. Yet overall trends reveal foreign languages to be faltering even at the collegiate level, considering that only 7.5% of U.S. students were enrolled in at least one language course as of 2016, the second lowest rate since 1960.

Portland State is no exception to this—at least inasmuch as funding allocation would seem to suggest. PSU has seen many language programs shrink—or completely disappear—over the last 10 years or so. In fall of 2021 for example, both the Chinese major and minor became completely unavailable for student admission. Now, PSU’s Middle Eastern languages are facing the same fate.

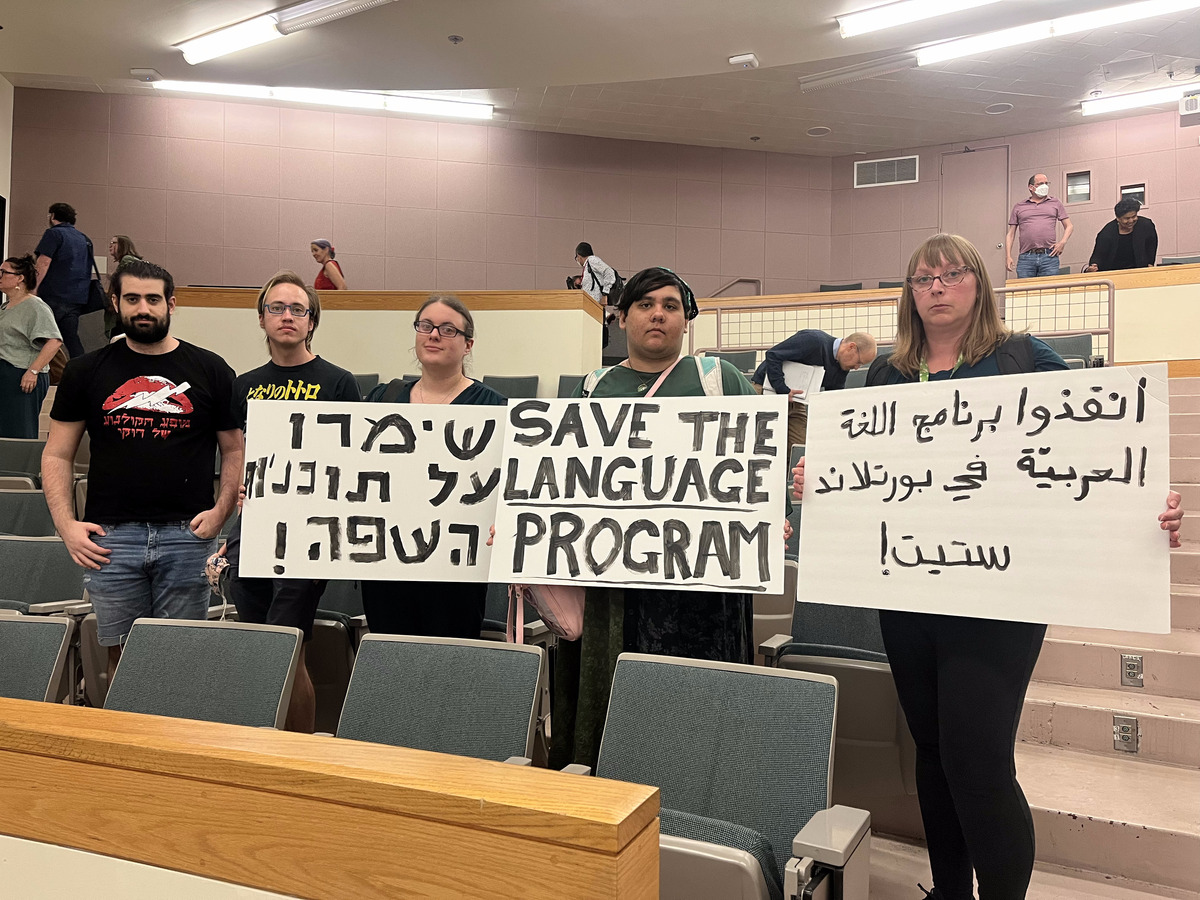

Quinn Bicer is pursuing a TEFL certificate, Middle East Studies major and Arabic minor, and is also president of the Arabic Club at PSU. Bicer is leading an active student resistance against the downsizing of the language programs, through the initiation of the Student Committee to Save Language and Cultural Studies at PSU.

The group’s online manifesto, “Fighting for a Multicultural Future”, opens with the following lines: “We present these statements and testimonials to you as an independent group of students who have been greatly harmed by Portland State University and the program cuts that have been made so carelessly and with no student consultation.”

Bicer explained that he was excited to study Turkish and Middle Eastern Studies at PSU to learn more about his own Turkish heritage, but soon found that the Turkish language program had already been cut, and was later told that the Middle East Studies major would soon follow.

Without Turkish as an option, Bicer chose to study Arabic from the Middle Eastern languages. “Because it was the most widely spoken,” he said. “This is probably going to be the most useful, and I’ll be able to talk to the largest amount of people, but when I started actually learning it, I was like, wow, this is actually so fun and I just really love this intrinsically.”

At that point, Bicer decided he would double major in Arabic and Middle East Studies, but could only officially declare Middle East Studies as his major since the TEFL certificate occupied one of the two degree slots available on PSU’s registration site Banweb. “I couldn’t undeclare Middle East Studies because they scrapped that like my first year here, so me being declared as that was my only insurance, to where I know they would have to let me finish it,” Bicer said.

Only after consulting various academic advisors did Bicer discover that the Arabic major was no longer available to pursue either. Subsequently, he was unable to continue working with his thesis advisor, since advising was specific to a major that was no longer accessible to him.

Bicer explained that even the MESC center was uninformed and excluded from PSU’s decision to cut the programs. Bicer cited a serious lack of transparency on the part of administration in regards to the downsizing. “No one talked to me,” he said. “No one talked to me about anything. I just assumed that everything was as normal, and like it would normally be in a college program.”

This desire for the higher-ups to improve communication is echoed by PSU staff. “Transparency is really important and transparency is not being achieved,” said Malcolm Goldman, World Language Requirements Specialist and Office Coordinator, in regards to reorganizing departments. “I think that things could go a lot more smoothly… if there was a concerted effort for administration to at least put guidelines or regulations on how to communicate with students during this process.”

The university’s rationale behind downsizing the language programs is rooted in course enrollment numbers and unavoidable budget deficits. “Pretty much all of the explanations are just very cold, hard—these are the numbers,” Goldman said. “Having read the faculty union’s report on that and the independent report that both the union and the administration requested, both of them say, actually you do have enough money—there’s just a lot of administrative bloat and things not going into places they should.”

“The cuts being very horse blinders on, only looking at numbers, is a really big disservice to students,” Goldman said. “Looking at it in a compassionate humanistic way, of like ‘here are students who want to study this thing, and humanities have value outside of just professionalism and within professionalism,’ I think that’s an important recognition.”

To blame budget cuts on low enrollment numbers is an oversimplification of the underlying structures necessary for program success in the first place. If a program is underfunded and understaffed, student enrollment will diminish as a consequence of those administrative choices. PSU’s ongoing hiring freeze demonstrates a perpetuation of this pattern—a practice that Goldman’s department experienced personally.

Goldman began working for the department of World Languages and Literatures in Nov. 2022, alongside two integral positions—the academic coordinator and the department manager. By May, both of these staff members had left their positions. While a temporary support position has been approved, Goldman remains as the only non-student staff member for the entire department. These vacant roles will not be filled due to the hiring freeze.

Because the administration has thwarted the department’s ability to adequately staff critical positions, the excess workload has been reallocated to the remaining staff in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences—with particular weight falling on Goldman and the department chair, despite the fact that “the department chair already has a lot of other tasks to balance,” according to Goldman.

Goldman also said that the distribution of labor has become increasingly inequitable. Ultimately, the holes in these support positions stunt the growth and success of each respective language program. “Faculty don’t have the support they need in order to focus on teaching their classes,” Goldman said.

“All of that trickles down to student success,” Goldman said. “Students will have a harder time interacting with faculty because the faculty is gonna be stressed out doing other stuff that they really shouldn’t need to be doing.”

One such task that often falls unfairly on professors is the promotion and advertising for course offerings and program events. “ I wish there was sort of a larger coordinating media body that knew how to do that… because I wish that my job was not about PR,” said Jon Holt, professor of Japanese. “I wish that I could focus on one, teaching—two, my research. Because those things go hand in hand, so that would make me a better professor.”

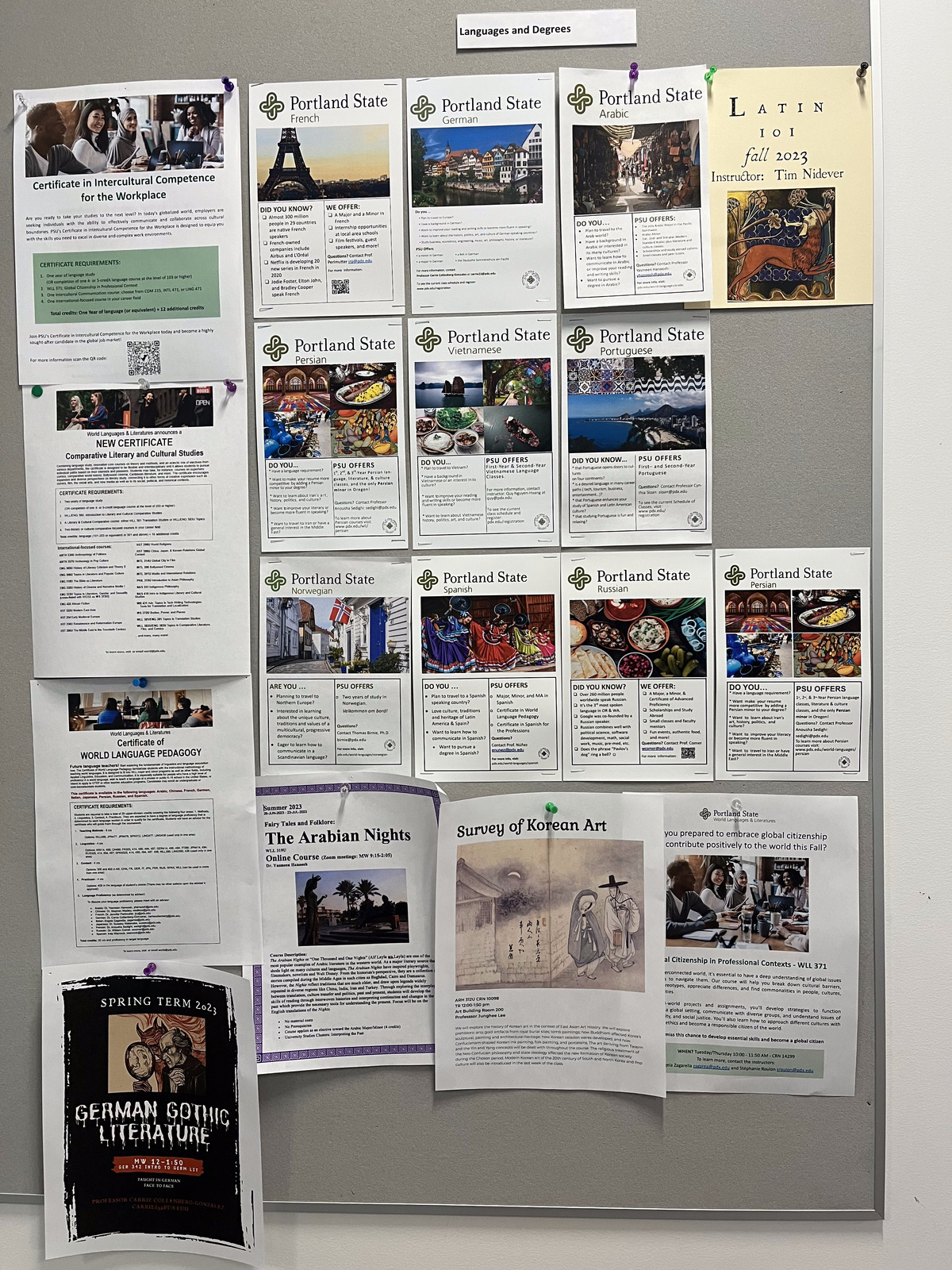

Many of the language programs at PSU are not offered at any other Oregon schools, and in some cases these language degrees aren’t even offered anywhere in neighboring states. “The university could do a better job of promoting, selling, advertising, our language programs,” Holt said. “Where else in the state of Oregon are you going to learn Persian? Or where else are you going to be able to learn four years of Japanese? PSU offers so many options to students.”

Holt explained that the Japanese program has maintained consistently strong enrollment numbers throughout his 10 years at PSU. “We still have, you know, 20 to 35 people graduating with Japanese majors or minors every year,” he said. “I’m busy. I stay busy.”

Despite the administrative narrative that enrollment numbers determine downsizing, even the Japanese program has suffered from budget cuts. “If they ask us to make cuts, I get it,” Holt said. “But if they feel like certain things are strong, they should not cut it. They should promote it. For example, summer classes are a really contingent issue.”

Historically, PSU has offered many language courses in a condensed summer format, the equivalent of an entire academic year of language in just a summer term. These programs allow students more leeway to organize their other courses during the academic year, and also offer an opportunity to fulfill the two-year language requirement in just 12 months.

Aside from the scheduling benefits, this format is simply beneficial for intellectual growth. “For language learning, because you really need to practice it every day and practice it a lot every day, it’s so amazing, and you really get these star students who emerge there,” Holt said.

PSU has been offering Japanese in the summer since 1985. Cuts to those offerings began in 2013, and summer 2023 will mark the first summer in which no Japanese courses will be offered during the term.

These types of formats are often taught by graduate students with assistantship positions. Holt explained that cutting the summer programs “has been very painful, and painful in a number of ways because you’re not giving the chance to students who want to move quickly, and you’re also cutting out funding for GTAs.”

Ultimately, the language units at PSU contribute to student integration on campus, marketability in the workplace and the personal satisfaction of multilingualism. The faculty, cultural events and academic challenge associated with studying these languages provide support for student success, but also foster connection between PSU and the diverse community of Portland.

“The idea of PSU promoting itself as a diverse institution while centering only on English speaking classes and English cultures, just isn’t—you can’t call yourself diverse without having an opportunity to learn about other cultures from those other cultures’ perspectives, and that’s what you do with language courses,” Goldman said.

“A lot of these languages that are getting cut, are languages that have a really significant presence here at PSU and in the greater Portland area, with people who moved here from other countries, and international students,” Bicer said.

“If you cut all the language programs it’s like you’re shutting out so much of the world,” he continued. “There’s so much culture and history that’s documented in other languages and there’s a whole ocean of information and connections that come from knowing any other language.”