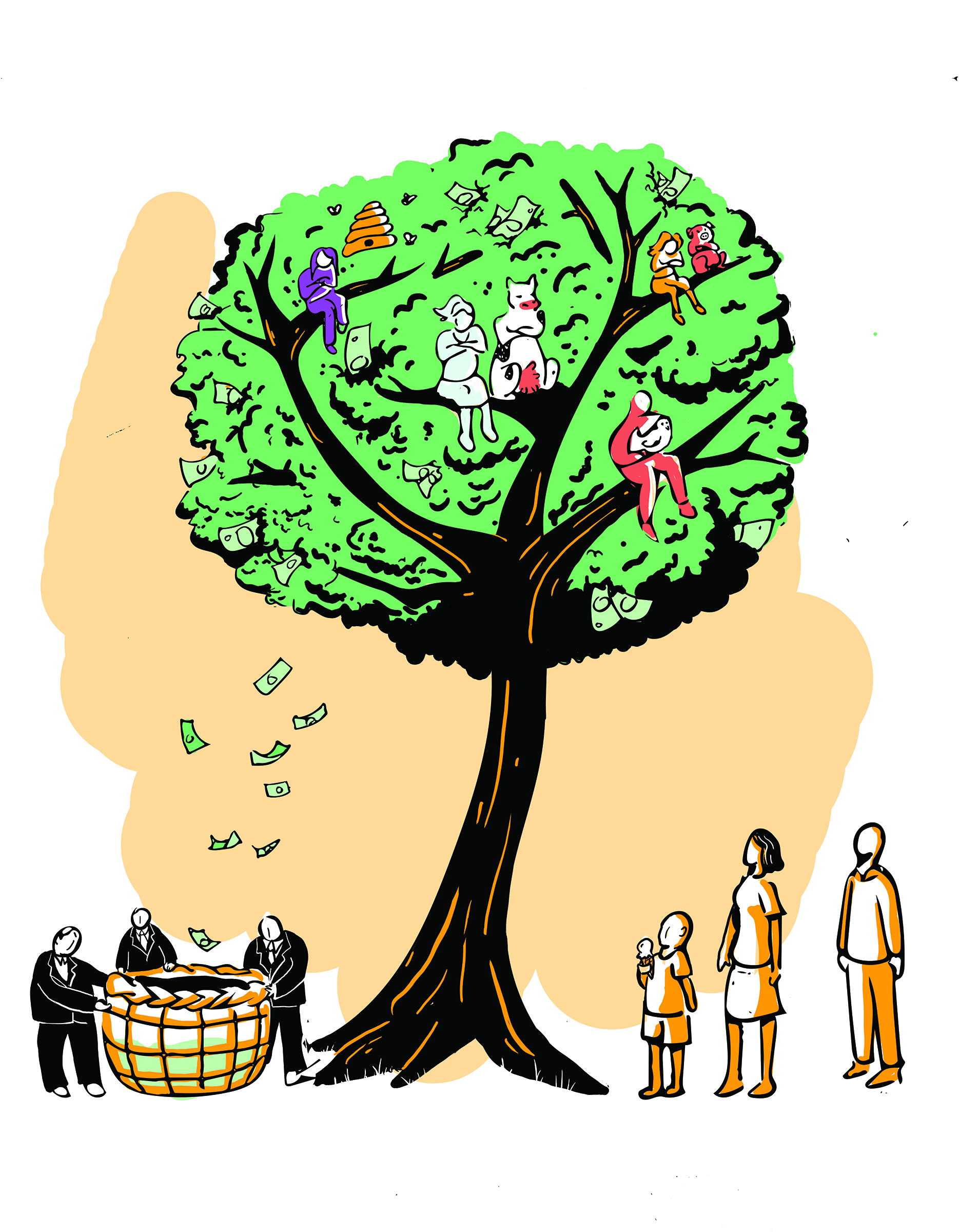

When almost any holiday approaches, there will be a considerable increase in ads and promotions which are hoping to make money from the celebration.

During Valentine’s Day, the theme of love often leans towards traditional romantic relationships, emphasizing partners expressing affection for one another. The marketing strategy revolves around the desire to impress or dazzle one’s significant other, serving as a means to prove one’s love.

This is not meant to shame individuals who purchase holiday-themed promotions from companies. However, it’s essential to recognize how marketing endeavors often aim to persuade—and even coerce—consumers into believing that their offerings are superior or the only worthwhile option.

Advertising is inherently persuasive and manipulative, whether through explicit statements, such as “Show her how much you care” accompanied by overpriced jewelry sets, or indirectly through subtle cues, such as color coordination in stores and repetitive ads which create a sense of urgency.

This is hard to map with singular instances, but we all see and feel it around us. The ads change, and you learn about the upcoming holiday a month before from the change in display or targeted ads on Instagram feeds.

People react differently to this consumerism. Some feel annoyed at the bombardment of unnecessary material goods, while others grapple with the profound uncertainty of determining the appropriate response to the holiday. Whichever way you respond to the plethora of consumerism doesn’t matter as much as the fact that it will impact you.

One of the most considerable criticisms about how businesses promote deals and encourage consumption for any holiday is the manipulative suggestion for the need to prove your love—as if love isn’t a continually changing aspect of the relationship which often needs continual, unscheduled maintenance.

Advertisements often convey that the most meaningful expressions of affection come with hefty price tags or lavish gift baskets. Companies vie for a share of consumer spending by presenting their offerings as enticing good deals.

Alternatively, specific industries rely on the enduring prestige of traditional gifts such as roses, jewelry or a romantic night out.

Valentine’s Day is an interesting part of this trend, because it focuses on the insulated romantic relationship dynamic popularized in heteronormative expressions of love.

“Gift-giving is my love language,” you might say, but even that is buying into an idea made up 30 years ago by Baptist Pastor Gary Chapman.

While the concept of the five love languages serves as a metaphor for expressing and perceiving love, it lacks empirical verification. Despite its seemingly harmless nature, this framework categorizes expressions of love as distinct languages, potentially enabling individuals to dismiss their partner’s need for affirmation by rejecting that particular love language.

Researchers studying this analogy propose a more fitting comparison with a well-balanced diet, emphasizing the necessity of a broad range of essential nutrients to foster lasting love.

The book The 5 Love Languages: The Secret to Love That Lasts—written by Chapman—has achieved widespread success with over 20 million copies sold. This makes it pretty lucrative for a metaphor lacking any evidence-backed research on how relationships are actually sustained.

Creating love is its own market and has been for quite some time. Now, we can see the muck that results from it, such as dating apps. Given that the purpose of dating apps, inherently, is not to foster successful relationships. Otherwise, their necessity and profitability would diminish.

Take Tinder, for instance, which offers three subscription tiers. Yet some users stay on the platform for extended periods with little to show for their efforts.

The holiday season—particularly Valentine’s Day—tends to evoke feelings of shame and guilt, especially for those who are single. Pessimistic individuals often find solace in expressing their disdain for the holiday, rightfully so.

The pervasive marketing surrounding Valentine’s Day impacts people beyond direct purchases, influencing people regardless of whether they buy couple-centric items.

A potential remedy might be indulging in a personal treat, but this immediate satisfaction—often found in online shopping—can inadvertently perpetuate a loop of loneliness.

So it doesn’t really matter if you are in a relationship. The marketing narrative emphasizes the expectation of being in a relationship and prompts individuals to make purchases which either showcase their deep love or address their perceived loneliness.

While fostering meaningful connections is essential, it’s crucial to recognize that this holiday shouldn’t equate to a one-day assessment of a relationship’s value or one’s worthiness of love.

Divesting from consumerism isn’t easy, but a meaningful expression of love should not have to be bought.