Portland is home to a robust and diverse community of artists and creatives. You will not have to travel far from Portland State to experience it. Right on campus—inside Fariborz Maseeh Hall—is a free and public art museum with shows, events and exhibitions evolving all year round.The Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA at PSU) is a collaborative institution which intends to resonate with students across all disciplines, not just those studying art.

Currently on view at JSMA at PSU is an exhibition titled A Question of Hu: The Narrative Art of Hung Liu from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation. This body of work features paintings, tapestries, lithography and collages created by the late Chinese-American artist Hung Liu.

Born in 1948 in Changchun, China, Liu lived through the Maoist Regime’s Cultural Revolution, through which her family was forcibly separated. Liu was sent to a reeducation camp as a young adult to perform agrarian labor for four years.

During this time, she defied state suppression of photography and artistic expression by photographing and painting her fellow laborers.

She studied education at Beijing Teachers College and mural painting at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts before relocating to the United States in 1984, where she received her Master of Fine Arts from the University of California, San Diego.

Liu would become an art educator and one of the most appreciated artists of our time. When searching “Chinese-American artists” on Google, her name is the first result on the page.

In many ways, the works on display at JSMA at PSU pay homage to Liu’s homeland, with symbolic references to Chinese film and literature, depictions of Chinese landscapes and culturally symbolic flora and fauna. However, the exhibition’s name reveals an underlying principle broader than China.

The exhibition is named after The Question of Hu—a 1988 semi-historical novel by Jonathan Spence which follows the story of John Hu, a Chinese Catholic who accompanies a Jesuit missionary to France. The novel ultimately addresses a cultural exchange between China and western Europe, notably to the detriment of the migrant Hu.

A Question of Hu is also the title of one of Liu’s massive multimedia paintings. Changing The Question of Hu to A Question of Hu may seem an inconsequential edit, but from definite to indefinite the change in articles was certainly no accident. The painting is situated right at the entrance of JSMA at PSU, ushering in glances through the glass exterior of the gallery.

This piece layers a patchwork of postcard memories atop a rural Chinese landscape. Two colorful boxes jut out of the painting, jolting the tranquil image into 3D reality. On these boxes are miniature bonsai trees, which Liu purchased in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Like the novel, this work dissects the convergence of two places and two histories within the context of Liu’s identity as a Chinese immigrant to the U.S.

“One way that [bonsai trees] are molded is through using wire to shape where the branches go, and one interpretation of why Hung Liu incorporated this is that maybe she also resonated in the ways that she also was molded [to adapt to] U.S. culture,” said Anna Kienberger, education and communications coordinator at JSMA at PSU and PSU alumna.

Immigration, forced migration and citizenship are themes—present throughout this exhibition. This is visible in paintings such as “Western Wind,” which illustrates a Chinese couple migrating on donkeys, a sense of urgency palpable as one of them breastfeeds.

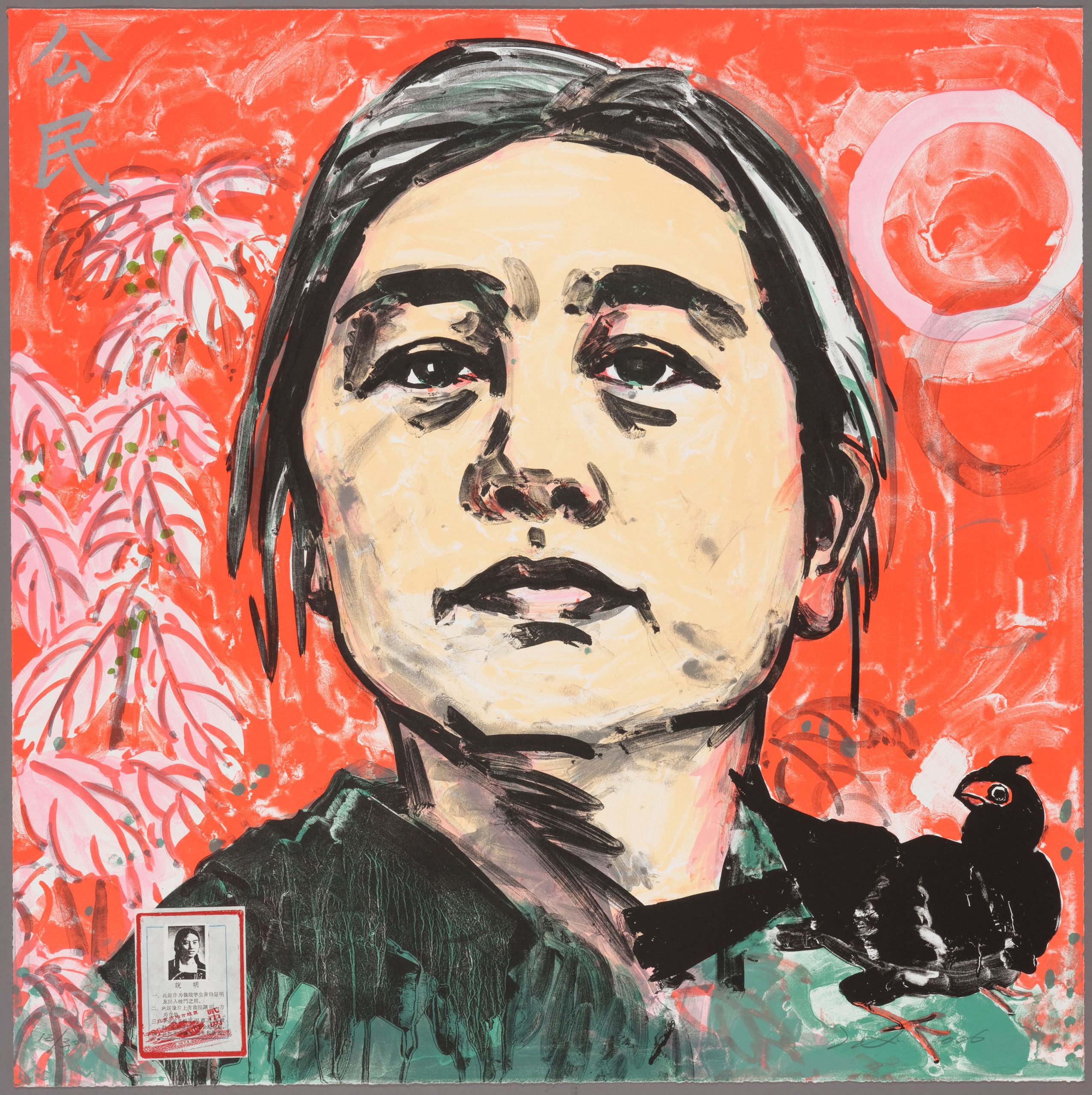

Similarly, a three-piece series of Liu’s official self-portraits features her Chinese identification cards in the corners of the canvases. The pieces are titled “Proletarian,” “Immigrant” and “Citizen” and raise questions of identity, belonging and legal personhood.

Another unique aspect of Liu’s work is her signature use of particular symbols and shapes throughout many pieces. Liu attributed the dandelion as a personal symbol representing “her ability to thrive in the face of adversity,” Kienberger said. “They’re able to migrate and travel over vast expanses, even over oceans and take root anywhere and not only survive but also thrive.”

Considering Liu’s artistic emphasis on the immigrant experience, it is unsurprising that her work would set the stage for Portland’s city-wide, biennial exhibition titled Social Forms: Art as Global Citizenship.

Social Forms is a free public event put on by the non-profit arts organization Converge 45. Liu is one of 50 artists whose work has been curated for this biennial and installed in various venues throughout Portland.

According to Converge 45’s website, the title Art as Global Citizenship “is designed to promote increased citizenship during a period of political polarization and retrenchment of civil liberties—where citizenship is a term used not to denote privileged political status but to propose a more inclusive category of belonging in the world.”

Thus, the art displayed in this biennial should reflect the same ideas as Liu’s work by deconstructing the notion that citizenship is solely a legal document.

“Citizenship is a fundamental right,” said Converge 45 curator Christian Viveros-Fauné at the opening ceremony for A Question of Hu. “It’s a right to have rights.”

“Without it, the vulnerable, the poor, the refugee[s] don’t stand a chance,” Viveros-Fauné said. “And this is the kind of period—the period that we’re living through, that Joe Biden has called the cascade of crises—this is exactly the kind of period in which we need aesthetics.”

Indeed, A Question of Hu utilizes this aesthetic magnetism for social progress. Liu elevates marginalized identities in her work such as farmworkers, refugees and sex workers—honoring the stories of those who are often dismissed and minimized.

“Hung Liu—especially with her subjects of women and children, but just her subjects in general—really wanted to show them [with] a sense of dignity,” Kienberger said. “One way that she does that is by offering them a kind of precious token in many of her portraits of them.”

In 1991, Liu returned to China and discovered photos of sex workers and victims of sex trafficking in a photography studio. Liu paints these subjects with tokens of honor, such as a crown of flowers, a golden medallion or butterfly adornments.

“I paint from historical photographs of people; the majority of them had no name, no bio, no story left. Nothing. I feel they are kind of lost souls, spirit-ghosts. My painting is a memorial site for them,” Liu said in an interview.

A prominent feature of these works is that the paint drips down the canvas, streaking certain aspects of the images to produce an effect reminiscent of streaming tears. In this way, Liu transforms the factual nature of these photographs into creations of abstraction and contemplation.

“She’s directly challenging the documentary authority of photography, as she is subjecting it to this really reflective process of painting, by creating this dripping wash…” Kienberger said. “She’s trying to directly reference how memory slowly seeps into history.”

The portraits within this exhibition include many histories outside of China as well. Liu was inspired by the Great-Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange, who was responsible for perhaps one of the most recognizable photographs in U.S. history, “Migrant Mother.”

Liu reimagines Lange’s photographs in larger-than-life paintings. “Sharecropper” foregrounds a young boy’s face overlaid on a bright tangerine backdrop. His image is filled with scrawling lines of neon color, blues, greens and yellows tracing the curves of his face and hair.

This colorful linework represents a topographical map, which Liu described as “hope, coming from the cracks between things.”

Liu’s artwork ultimately focuses on people living in dispossession. Liu depicts a shared human experience regardless of their origin or cultural background.

“This landscape of struggle is familiar terrain, reminding me of the epic revolution and displacement in Mao’s China,” said Liu about this era of her work. “Only now I am painting American peasants looking for the promised land.”

This exhibition considers a wide range of content matters and social issues. To provide greater student accessibility for engagement with these works, JSMA at PSU has organized educational programs and events for the PSU community.

JSMA at PSU and Converge 45 uphold art as a means of activism. A Question of Hu provides a point of entry for community-building and developing understanding among people from different backgrounds.

Nonetheless, the museum encourages an open narrative for onlookers, in which Liu’s art can take on any number of meanings specific to the person engaging with them.