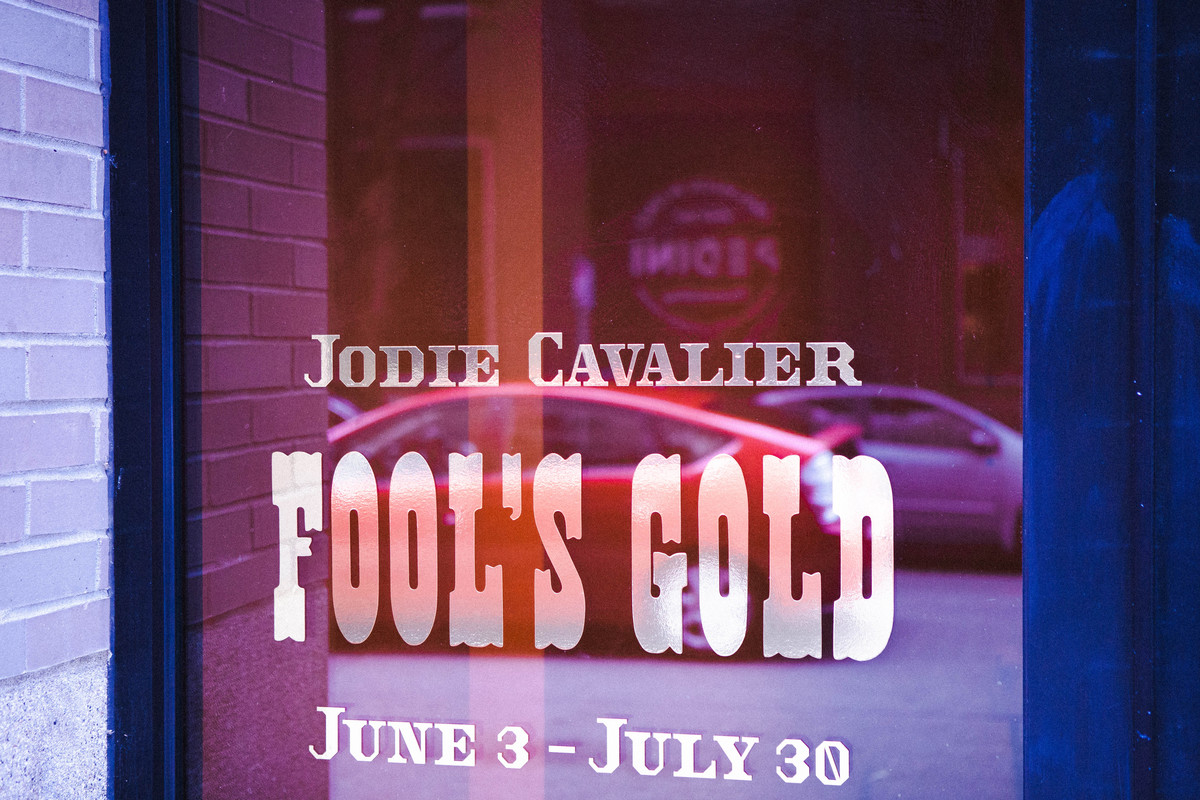

It’s clear from first glance that the Fool’s Gold exhibit transforms the gallery into something unique. As a result of the orange layer pasted over the usually clear windows at Portland’s HOLDING Contemporary gallery, the normally white walls inside appear neon orange. Upon entering the gallery, the orange light fades, but still subtly bathes the Pacific Northwest space in a light reminiscent of the Mojave Desert, where Fool’s Gold exhibit artist Jodie Cavalier grew up.

The subject matter of Cavalier’s work often revolves around the lives of her family members, and this project is no exception. It focuses on the life of Cavalier’s grandfather, who passed away from COVID-19 in 2021. Cavalier’s show is a multimedia project that uses ceramics, seemingly ordinary objects and a select few printed pieces to transform the gallery space.

The show runs from June 3 to July 30, with gallery hours from Friday to Saturday 12–5 p.m. A closing ceremony will be held on July 30 at the gallery from 5–7 p.m. and include a publication that will provide additional context for different pieces in the exhibit.

Her writing is a large part of her current practice and is what most of the show came out of, yet she said it didn’t feel right in the show itself. “I was thinking about how my grandfather didn’t know how to read, so I was like, ‘maybe it’s okay for it to come out of that, but it shouldn’t be the focus,’” Cavalier said.

She continued thinking about the type of man her grandfather was, eventually tying his approach to life into her decision to use ceramics as her main creative focus. “My grandfather was always tinkering around the house and working on projects,” she said. “He wasn’t educated; didn’t know how to read or write. But he always found these creative solutions and taught himself how to do things.”

Cavalier took up this spirit, embracing ceramics as the primary medium without formal training. “I have some experience working with ceramics over the years, but it felt right to explore making with a material I wasn’t fully trained in,” she said. “I think that’s been quite wonderful because it reflects a lot of the ways I imagine he navigated the world. Finding solutions to things and learning things on his own.”

Her journey with the medium included stumbles and multiple broken objects before arriving at how the show is today. Cavalier said that this natural exploration was crucial to her project. “There are certain things I made—like the handmade tools—that a trained ceramist would never attempt, because it doesn’t make sense with the material,” Cavalier said. “Me not knowing all the restrictions that clay has and learning along the way opened it up to some really creative, interesting objects.”

“The palette of the show is something I thought about at the very beginning of the show in order to make decisions and reign things in so as not to include everything,” Cavalier said regarding her use of color. Ultimately, she chose three colors for the show’s base color palette.

The first color was blue, symbolic of the blue denim and workwear her grandfather wore. “My grandfather wore blue jeans and a white t-shirt basically every day unless we were going to a funeral or a wedding,” Cavalier said.

Naturally, the next color she decided on was white as an extension of his daily attire. However, for her, it expanded beyond his clothes. “In southern California—don’t know if it’s just Mexican neighborhoods—the bottom half of tree trunks are painted white,” she said. “I was told as a kid it was to keep away a certain type of insect.”

As it evolved, the association of white extended to include white picket fences and decorative rocks from the lawns of her childhood, as well as connecting white with flour tortillas. “I thought about how all these sources of white push up against the white walls of an institution, a gallery space, a school space,” Cavalier said.

The final color she chose was green, linked with her grandfather’s sleek green work truck. This final color was ultimately less pronounced throughout the exhibit, and featured most prominently in the section titled Lunch as part of the stand that complements the work.

As she continued the project, she added additional colors inspired by found objects of her grandfather’s. Some objects Cavalier included for the way they complemented the themes and color scheme of the show, while others she chose due to how they displayed her grandfather’s personality.

One example is in the wrapped belts placed on the wall of objects. “They were these tender objects I found,” Cavalier said. “The pride and care that went into wrapping them and storing them in a particular way. There’s such tenderness and care, and it’s a way to showcase that through objects.”

Another object that shows her grandfather’s ingenuity is the abalone shell holding poker chips in the workstation section. “He just tied wire around an abalone shell and used it as a thing to hold screws and nails and things,” Cavalier said. “I was like, wow! I didn’t realize how much we shared sensibility in making. I don’t think he would ever have considered himself an artist, but I learned so much from him and embodied it naturally.”

She also touched on the importance of blurring the lines of formal training and her grandfather’s craftiness while not putting one above the other and letting both shine.

Themes of gambling, luck and wealth are apparent in the workshop scene and throughout the show in nearly every work. Cavalier explained how this vein of thought was essential to the show. “My grandfather gambled a lot, and I wanted to include that not so much in terms of addiction, but more so in the sense of dreaming,” she said. “I can’t speak for anyone else’s experience, but for me growing up poor was thinking about what it would mean to find gold or to be wealthy. Not so much a class difference. It was more so kind of an escape.”

She linked this directly with her work, saying, “For me creating a space in the gallery is a similar process of creating a different reality, headspace, or timeline you can operate on before you come to and are back in the reality of the situation.”

This idea is continued in the show by including both real objects of her grandfather’s and made pieces. “There’s a mixing of the fantasy and the dreaming with the more practical, factual storytelling,” Cavalier said. “Those two worlds are meshed together in the space.”

As a whole, Cavalier hoped that everyone could get something out of her show. “I want [people] to come through with openness and curiosity,” she said. “I want them to find a space where they can meditate on ideas that are complicated and sad and still find moments of beauty in them. For them to walk away with an entry point to do that for themselves in their own practice, whether it’s artistic or not.”