In a landmark feat for scientists, geneticists and health experts, the first complete sequence of the human genome has been mapped, announced on April 1, 2022.

Led by the Human Genome Project, 92% of the genome had been sequenced in 2003, beginning an international research project aimed at completing the final 8% of sequencing. With 19 years of collaboration, it has finally been accomplished.

A lot of science fiction jargon is thrown around when discussing the future of human genetics, which provides an unwanted opening for some largely cryptic opinions about how genetics work in humans—especially the impact on the field of medicine and scientific research.

The easiest analogy for a genome is to view all species as a cookbook. Any living being, plant, animal or fungi needs a recipe to build themselves with. Each living being needs different cells to do different things, and when those cells die, they need other healthy, living cells to replicate and function in much the same way. This is the natural cycle of how living organisms survive.

When cells don’t die at the right time—or when they don’t adhere to the cookbook of life—cancer is formed. The genome, much like a cookbook, encompasses the complete guide of all the different kinds of things a living organism can produce, from start to finish.

Naturally, within that cookbook, are recipes. These could be recipes for different cells, or different pieces that a being needs to produce in order to function. The recipes here can be thought of as genes.

At the end of the day, all recipes are a set of instructions. They tell you what you need, what to do and how long to do it. Each instruction in a recipe can be thought of as a strand of DNA. Think of a recipe for mac & cheese as the gene, and the instruction for boiling pasta as the DNA in the recipe of life.

So, where then, are the ever-contested and oft-cited chromosomes in this analogy? These little bundles of genetic data can be thought of as the categories inside a cookbook. If we see a gene as a complete recipe, a chromosome simply bundles recipes together in a certain functional order, no different than the soup section in a cookbook alongside the dessert section. Each gene inside a chromosome is often related, but still varies widely between organisms and for functions within an organism.

Each species carries different sets of chromosomes, and each chromosome has endless potentials for variation. Humans most often carry 23 pairs of chromosomes, creating a total of 46 chromosomes in all. Typically, one chromosome in a pair is inherited via the egg, and the other is inherited via the sperm. This is why chromosomes are often talked about in pairs—one from each parent.

Sex chromosomes are specific chromosomes that impact developmental functions such as genitalia and hormone production. These are usually described as either an XX chromosome pair or an XY chromosome pair, which many use as the basis to determine one’s sex.

However, as the Intersex Campaign for Equality details, an estimated 1.7–2% of the population actually carries a variation beyond these pairs, such as a single X or a triple XXY set of chromosomes. Nature is never bound to adhere to strict rules in every instance.

To place this into perspective, if the United States has 300 million inhabitants, this would mean that 5–6 million people are born with a set of chromosomes beyond the binary pairs of XX or XY. 6 million individuals should hardly be considered outliers in our diverse society. This is evidence of the human genome’s variability and flexibility.

These chromosomes are important to discuss because these have actually accounted for a majority of the 8% of genetic data that the Telomere to Telomere (T2T) consortium dedicated itself to mapping, in collaboration with the Human Genome Project.

The euchromatin regions—the less dense DNA material that is more active and shared amongst all humans—accounted for the original 92% of the genome that had been mapped by 2003.

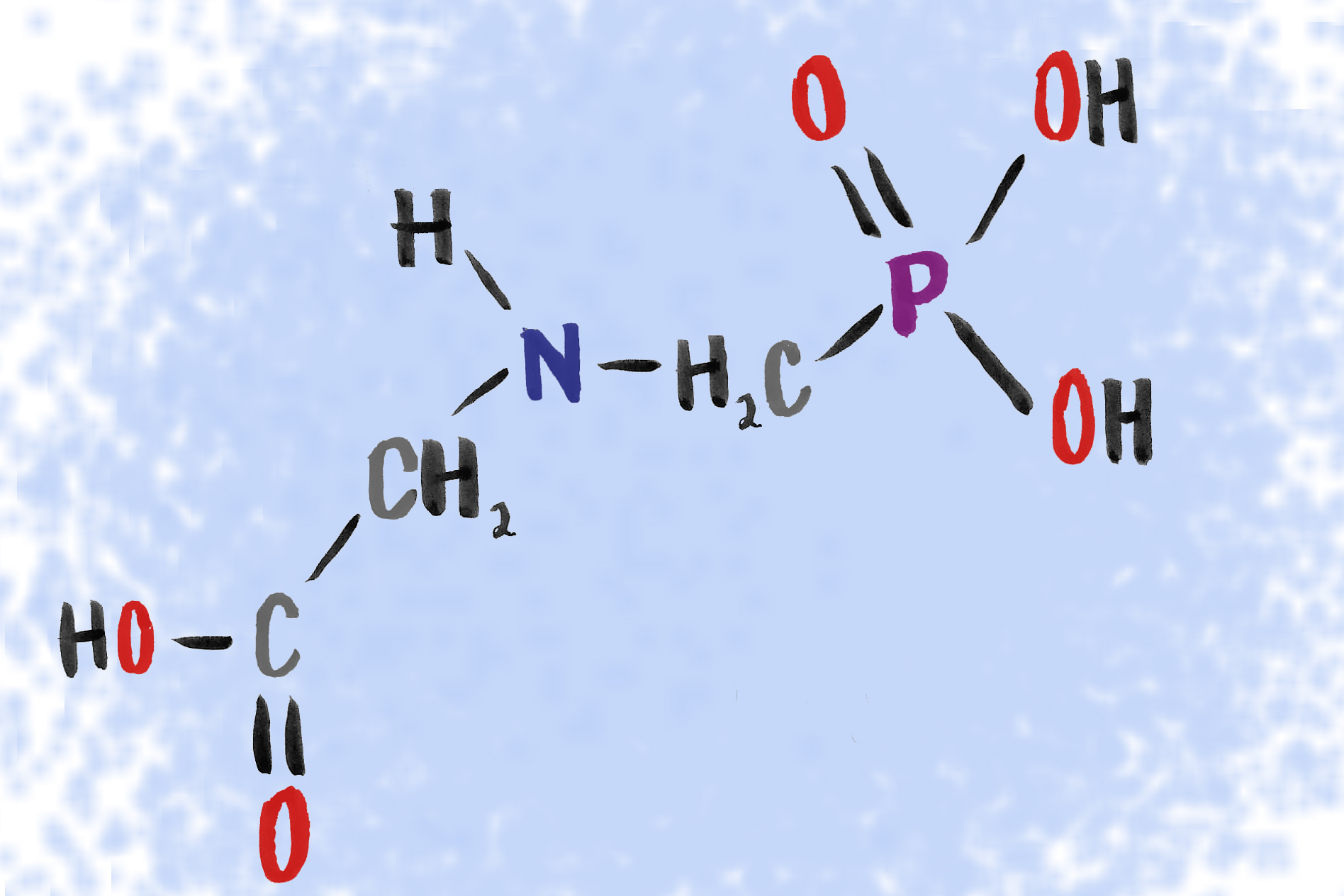

With the advancement of technology and medicine, the strands of DNA that were previously too dense to break through, but were found most often in sex chromosomes—known as heterochromatin or the dark matter of our genetic structure—have now been uncovered.

This is only the first step in our understanding of the material that makes us unique. While this section of the genome has been mapped, it is not yet understood precisely what instructions these sequences do. Since this research mapped chromosomes individually and independently, it does not yet look at the cookbook as a whole, but rather what can be found in each section of the book that tells us who we are.

For now, it is our responsibility to ensure that the research conducted remains ethical, moral and used only for the purposes of enriching the lives of those who may suffer from debilitating and lethal genetic disorders.