“Now is the time to act, the 2017 legislative session for every state in the country. You need to set strict environmental policies now because the federal government is not going to be helping us out,” said Alexander Krokus, founder of Associated Students for Ethical Environmental Policy at PSU.

Genetically modified organisms and biotechnology foods are increasingly integrated into agriculture management around the globe. Effects of biotechnology are studied and tested, and as the industry matures, arguments for its efficacy and safety become ever more divisive. Meanwhile, agrochemical companies are merging and acquiring each other, shifting countries of governance and methods of operations and regrouping market shares.

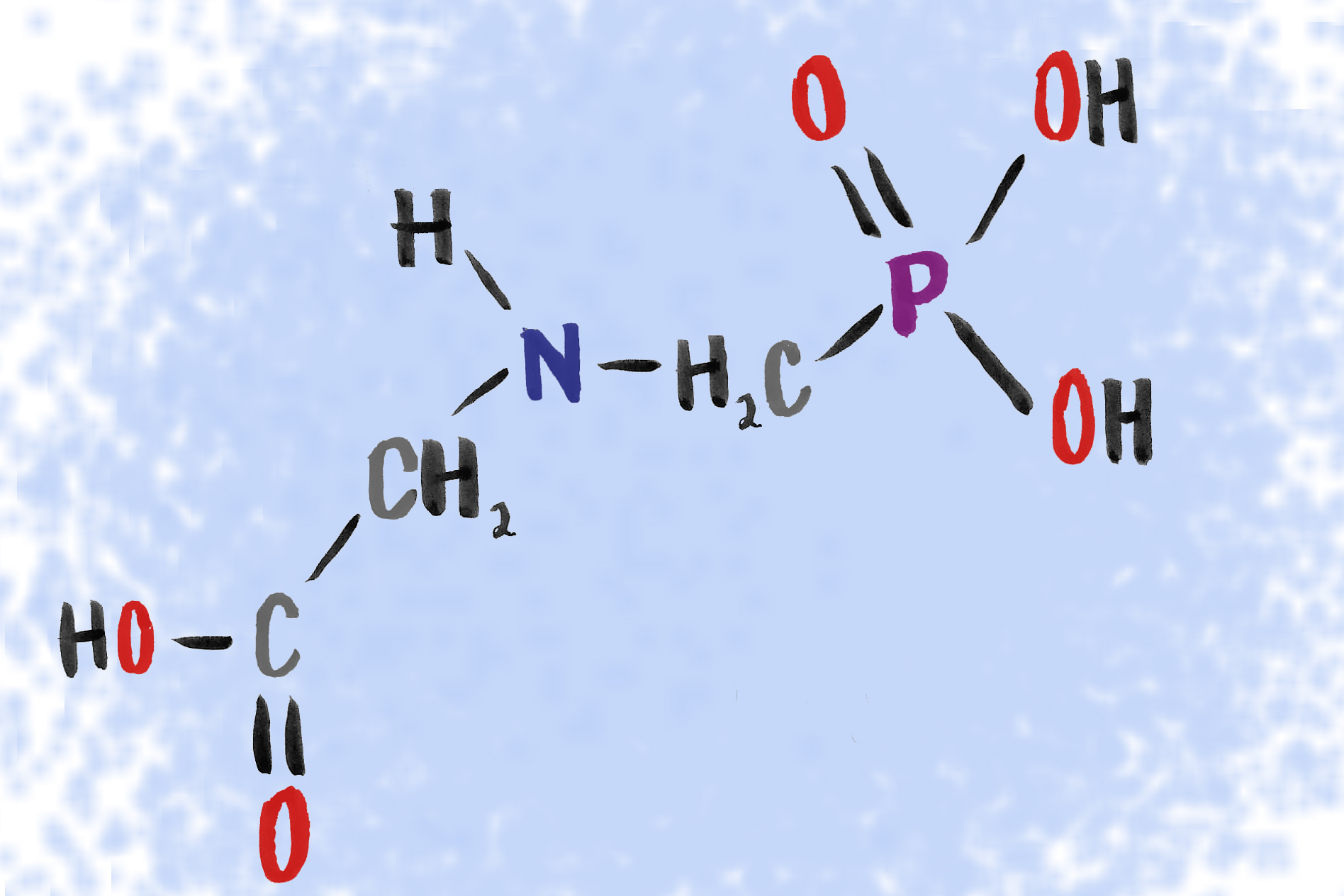

In the United States, one of the most commonly known agrochemicals is glyphosate, the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup. Glyphosate was engineered to kill vegetation and is applied locally in yards and parks and globally on crops.

The City of Portland, which owns and manages the Downtown Portland Park Blocks, uses approved herbicide products which contain glyphosate.

The area of the South Park Blocks that runs through PSU’s campus, however, is maintained by the university, not the Portland Parks & Recreation department, according to PP&R Media and Community Relations Representative Mark Ross in a Jan. 31 email.

“[P]er an agreement between [PP&R] and PSU…Portland State takes care of maintenance endeavors on the portion of the South Park Blocks that is on PSU property,” Ross wrote.*

The widespread commercial use of agrochemicals took off in 1996.

To keep glyphosate from killing the plants it’s intended to protect, crop seeds have been genetically modified to tolerate the herbicide.

Today, GMO and biotechnology products are incorporated in agriculture management around the globe. As sales have grown, so too have the arguments for and against.

PSU STUDENTS IN ACTION

“You see all these posts on Facebook about Monsanto and how the chemicals they are putting in the food relates to cancer and affects people’s health negatively—obviously,” said Portland State integrated health major Halle Wilkening. “The people affected are the lower class—the people who can’t really afford organic, non-gmo food.”

General population studies based on chronic agrochemical exposure compared to non-exposure showed adverse developmental or neurological outcomes, reported Environmental Health Perspectives. The outcomes included: Tetralogy of Fallot, a rare condition caused by a combination of four heart defects that are present at birth; anencephaly, the absence of a major portion of the brain, skull and scalp that occurs during embryonic development; autism spectrum disorder; and cancer symptom clusters including memory loss and finger tremors.

Use of agrochemicals and other environmental and health concerns are the passion of PSU student activist group Associated Students for Ethical Environmental Policy, which advocates for concerns involving campus and park maintenance, onshore wind farm development, genetically engineered salmon and global agricultural practices. Currently ASEEP has four members and is in the process of becoming a recognized student group, which receives funds partly based on the number of members.

“I’ve interned with the People’s Tribunal, which holds large corporations accountable,” said ASEEP founder Alexander Krokus. He currently interns under Oregon Senator Lew Frederick.

The mission of ASEEP is to research environmental legislation, submit personal testimonies, and verbally testify before Portland City Council and state legislators in congressional committees. They use government sources to debunk poorly written bills and offer more environmentally friendly solutions.

“We will also develop citizen lobbying efforts to influence policy advisors,” Krokus said. “I’ll be going down to Salem a few days a week.”

Glyphosate is a major concern to ASEEP.

Studies indicate that there is potential for “commercial formulations containing glyphosate to cause endocrine related harmful effects at low levels over long periods,” reported the University of Caen Normandy.

In Natural Society, Mike Barrett wrote, “[The] connection between the top selling herbicide Roundup and its causing of birth defects and disruption of male hormones [are] due to the main active ingredient—glyphosate.”

In March 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” but didn’t provide any hard facts due to limited evidence. The declaration continued, “There is convincing evidence that glyphosate also can cause cancer in laboratory animals.”

POTENTIAL BENEFITS

“‘We are outraged with this assessment,’” Monsanto’s Chief Technology Officer Dr. Robb Fraley rebutted on March 23, 2015, in a quote from Monsanto Newsroom. “‘This conclusion is inconsistent with the decades of ongoing comprehensive safety reviews by the leading regulatory authorities around the world that have concluded that all labeled uses of glyphosate are safe for human health. [The] result was reached by selective ‘cherry picking’ of data and is a clear example of agenda-driven bias.’”

Using glyphosate enables farmers to kill weeds that are detrimental to crops without the practice of tilling. Eliminating the use of tilling curbs soil erosion and runoff while increasing soil cover, soil aggregation, water infiltration and elevated soil organic matter development. One of the benefits of genetically modified seeds is they reduce the need for spraying during crop growth and maturation. Spraying is expensive and polluting due to wind drift.

Monsanto’s website states, “Comprehensive toxicological studies in animals have demonstrated that glyphosate does not cause cancer, birth defects, DNA damage, nervous system effects, immune system effects, endocrine disruption or reproductive problems. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency classified the carcinogenicity potential of glyphosate as Category E: evidence of non-carcinogenicity for humans.”

Insects are another burden crops. To resolve this problem seeds are genetically modified. This allows plants to be selectively poisonous to certain pests, such as ear worms in corn. Again, this practice cuts down on the times per growth stage that crops need to be sprayed.

“Many studies have been done on the health risks of glyphosate,” concluded the Environmental Sciences Europe in the article “No Scientific Consensus on GMO Safety.” The group reported that results were varied or suffered from lack of consensus.

Since widespread commercial sales started in 1996, the time lapsed may not be enough to accurately gauge long-term health and environmental effects of GMOs and biotechnology.

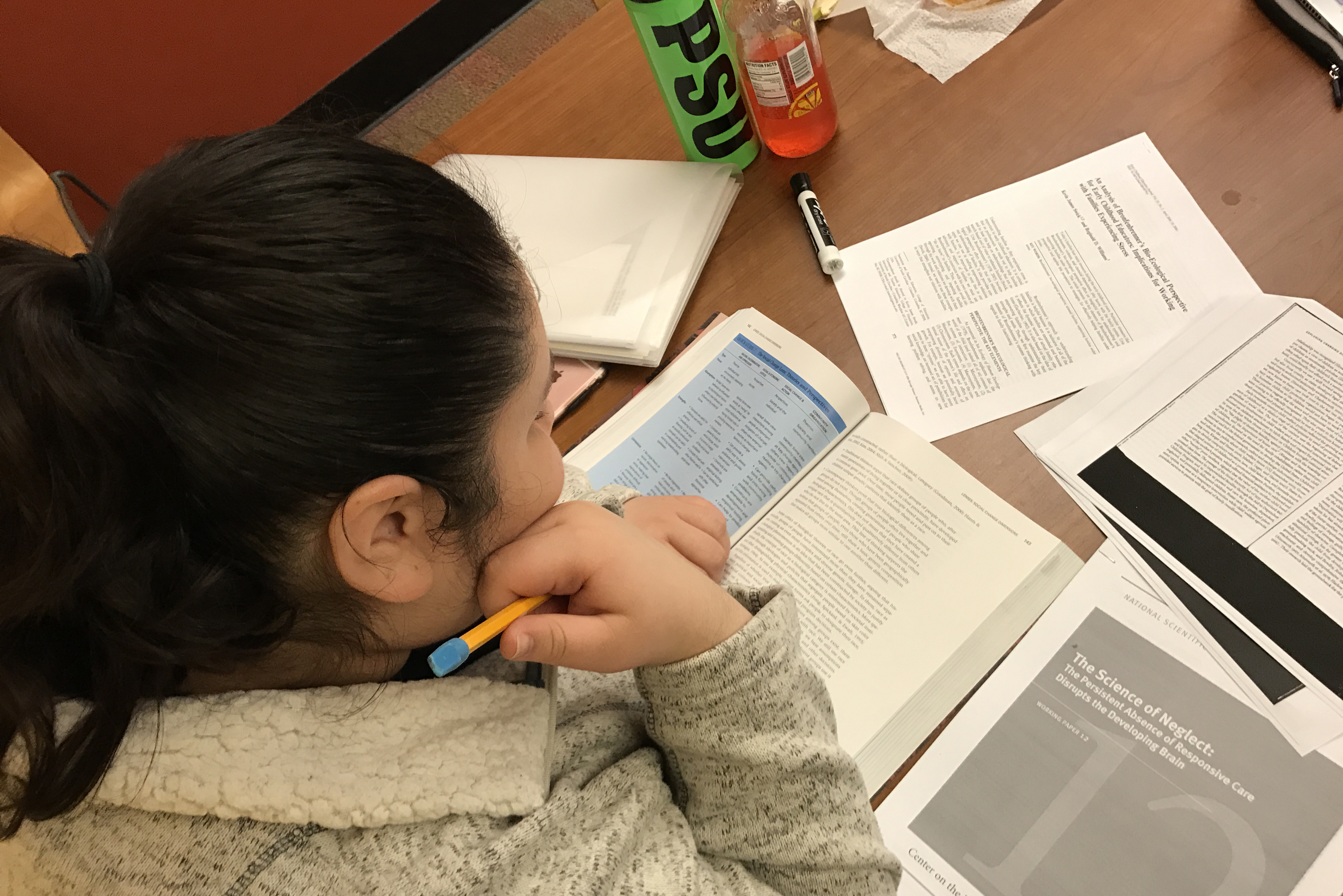

“Do they get tested in every circumstance?” asked current PSU student and retired organic chemist Dr. Walter Greizerstein. “At every step of research and development of products you use the best available information at the time.”

PCB’s, or Polychlorinated Biphenyls, have become common terminology when talking about hazardous chemicals produced commercially since 1929 according to Environmental Chemistry..

PCBs are no longer available in the U.S., although the use of of PCBs in floor finishing products has shown to be effective for fire prevention. “A lot of people were killed by fires in floor finishes in tenements,” said Greizerstein. “We saved a lot of people from dying by burning and we created problems with PCBs. Someone has to do all that evaluation, and someone has to sit down and say what are the benefits. Are there other ways to prevent fires? Yes.”

In Geizerstein’s opinion, feeding the world’s population and water scarcity is a large concern. He asserts that we need to have more effective agriculture management.

“We need to be more clever about how we handle GMOs,” Geizerstein said. “Eliminating them will create a lot more hunger, a lot more death, a lot more plagues. We need a better understanding of the problem. Just to stand in the way is misplaced dogmatism. University students ought to recognize that there is a benefit in knowledge, and in discretion, analysis and intelligence. We go to school to think. Stop and think.”

FEEDING A GROWING POPULATION

“You don’t want to be ingesting anything toxic,” said biology and premed student Page Murphy. “[But] we don’t want to not have a lot of food either.”

One of the biggest users of GMO and biotechnology products is the United States. Corn is one of the United States’ prime crops and 89 percent is genetically engineered. Many foods contain corn products, such as cornstarch and corn syrup—it’s virtually everywhere. The World Health Organization suggests ingesting chemicals such as glyphosate through a secondary source would not casually saturate the body enough to cause harm. Guidelines of safe and harmful consumption have not yet been established.

The argument in favor of GMO and biotechnological agriculture management claims that seeds may be fortified, resulting in produce that has, for instance, increased amounts of certain vitamins. Agrochemical companies argue their products are helping to raise the quality of health in regions where diets are otherwise deficient.

An overall argument is the question of how to feed the rapidly growing global population. Produce from GMO and biotechnology plants grow faster with fewer resources and are enriched with needed nutrients.

“We are more than six billion people on the Earth,” said Mubarak Mobarak, a Morocco native. “It is not easy to give them all food by using the natural practices. We need modern practices. It’s difficult to find food for everyone; that’s one reason for GMOs.”

“We’re dealing with biology,” explained Paul Minehart, finance and federal corporate affairs officer at Syngenta. “The kinds of things that affect [farmers’] crops are things like insects and disease and weeds. We’re a very R&D-intensive kind of business. We have to be continually innovating and developing new products and solutions for farmers to keep ahead of what their demands and challenges are.”

CHANGING RELATIONS

“They restrict their farmers in the sense that they restrict their seeds, and then with those seeds they can’t use them in the following years,” Wilkening said. “Each year they have to buy and repurchase seeds, which is interesting and sad. They are just really getting the most money out of them as they can.”

Around the globe, six mega-agrochemical companies are merging into three. Anticipated mergers for 2017 are Bayer and Monsanto, along with and Dow Chemical and DuPont. Syngenta is in the process of being purchased by ChemChina.

Bayer was founded in 1863 by a businessman and a dyer performing experiments using their kitchen stoves. In its 153 years of existence, Bayer has grown, stumbled and morphed into one of the globe’s largest innovators of agriculture products. Based in Germany, Bayer operates under its supervisory board, the German Corporate Governance Code. Through its signatory with the United Nations Global Compact, Bayer undertakes, among other initiatives, “to support the protection of human rights within its sphere of influence, to guarantee international labor standards, to improve environmental protection, and to fight corruption and bribery,” according to its website.

Monsanto is one of the largest multinational chemical companies, along with being a global mega-company in the seed industry. Founded in 1901, its first product was saccharine and it began producing and marketing agricultural chemicals in 1945. In 1982 it produced the first genetically modified plant cell. In 1964 the herbicide Ramrod was introduced, and in 1996 Monsanto introduced in-seed insect protection. Through the years, Monsanto has purchased interest in other companies that produced agriculture products, such as Calgene and the Jacob Hartz Seed Company. Headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri, Monsanto operates under U.S. laws and regulations.

Monsanto’s shareholders approved a $66 billion acquisition by Bayer. The completion of the deal is expected late this year and was widely publicized in December 2016.

Fortune Live reported that once Monsanto and Bayer combine, they will own 28 percent of the seed and pesticide market shares.

“Scientists at DuPont and around the world are working hard to improve food nutrition that will help reduce health-related deficiencies through biofortification, the process of breeding critical vitamins and micronutrients into crops,” states the DuPont website. For 2016, Dupont expects full-year operating earnings to have increased 17 percent.

Dow Chemical is headquartered in Midland, Missouri. Its 2016 third-quarter financials show an increase of 11 percent.

The Dupont merger with Dow is anticipated to occur in the first half of 2017.

The mergers of Bayer and Monsanto and Dupont and Dow would allow enriched opportunity for research and development. It would also bring into consideration disadvantages and advantages to the laws and regulations of each company’s country of operation.

Syngenta, globally headquartered in Basel, Switzerland, was formed in its current state in 2000 by combining the agrochemical branches of Astrozenit and Novartis, Minehart explained.

Syngenta’s website states they have 28,000 employees in over 90 countries. Reported sales for the third quarter of 2016 were $2.5 billion. In the global food industry their focus is on cereals, corn, diverse field crops, rice, soybeans, specialty crops, sugarcane and vegetables.

China National Chemical Corporation, ChemChina, posits, “Life needs chemicals.” Based in Beijing, it employs over 140,000 people and has operations in 150 countries and regions. Revenues for 2015 were reported at $45 billion. ChemChina produces products for many industries. Its agrochemical specialties are chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

ChemChina’s purchase of Syngenta will leave Syngenta intact but with a new owner, according to Minehart.

“We maintain our management, our products, our location,” Minehart said. “We’ll still be exactly who we are in terms of providing what we do for our customers and other stakeholders. Essentially it’s business as usual with us, even though that’s not the case with some of the others.”

“We have to get approvals from various countries around the world,” Minehart explained. “We operate in about 90 different countries. Now, we don’t have to get approvals in all those 90 countries, but there are a number that we do. We’ve got about 13 already. Significantly, there was a national security review, not in the United States, and we’ve already completed that one. We have not completed the antitrust approval in the U.S. yet, but that is well under way. It’s all moving along very well.”

Syngenta’s purchase by ChemChina will likely occur in 2017.

“We certainly hope to grow our market share, but it doesn’t automatically change with being acquired by ChemChina,” Minehart concluded.

THE HANDS THAT FEED US

“At a certain point people are going to die, there is just no avoiding that,” said PSU political science student Bien Metcalfe. “The way nature works is there is too many people and not enough food, so some people die, and then there is enough food for everybody that’s left. I think at a certain point that’s what’s going to happen.”

Concerns raised by the merging and purchasing of these companies encompass their diversity of laws and regulations, their potential control of the global seed market and reproductive potential of seeds, as well as a monopoly by a few mega companies on the insecticide and pesticide industry.

Another concern is that we live in a multiplying population, and food and water shortages are a major obstacle in our future.

To get involved in ASEEP contact Alexander Krokus at akrokus@pdx.edu.

Additional reporting by Jon Raby.

*Editor’s Note: Updated Jan. 31 at 1:18 p.m. to include clarifying follow-up information from PPR.