The United Nations International Court of Justice unanimously ordered Myanmar’s government to prevent genocide against ethnic minority Rohingya muslims in the country on Jan. 23.

Since Aug. 2017, Myanmar’s military has drawn sharp criticism from the international community, including charges of genocide and other violations of international human rights law for attacks on Rohingya communities along the western coast.

The military crackdown began in Oct. 2016 after militia members from the persecuted minority group attacked border posts, killing nine police officers, according to Myanmar official reports. Following more attacks in Aug. 2017, Myanmar stepped up military operations. In what one UN official has described as a “scorched-earth campaign,” Myanmar’s military began burning Rohingya villages, precipitating a mass-exodus of Rohingya from the country.

Since 1982, the Rohingya have been a stateless group—unrecognized as citizens by the Burmese government—and have been barred from participating in Myanmar’s political process.

The ICJ’s ruling is intended as a temporary stop-gap measure to prevent more violence against the Rohingya. The ICJ needs time to investigate the genocide charges, brought before the court by The Gambia under the provenance of the 1984 UN Genocide Convention.

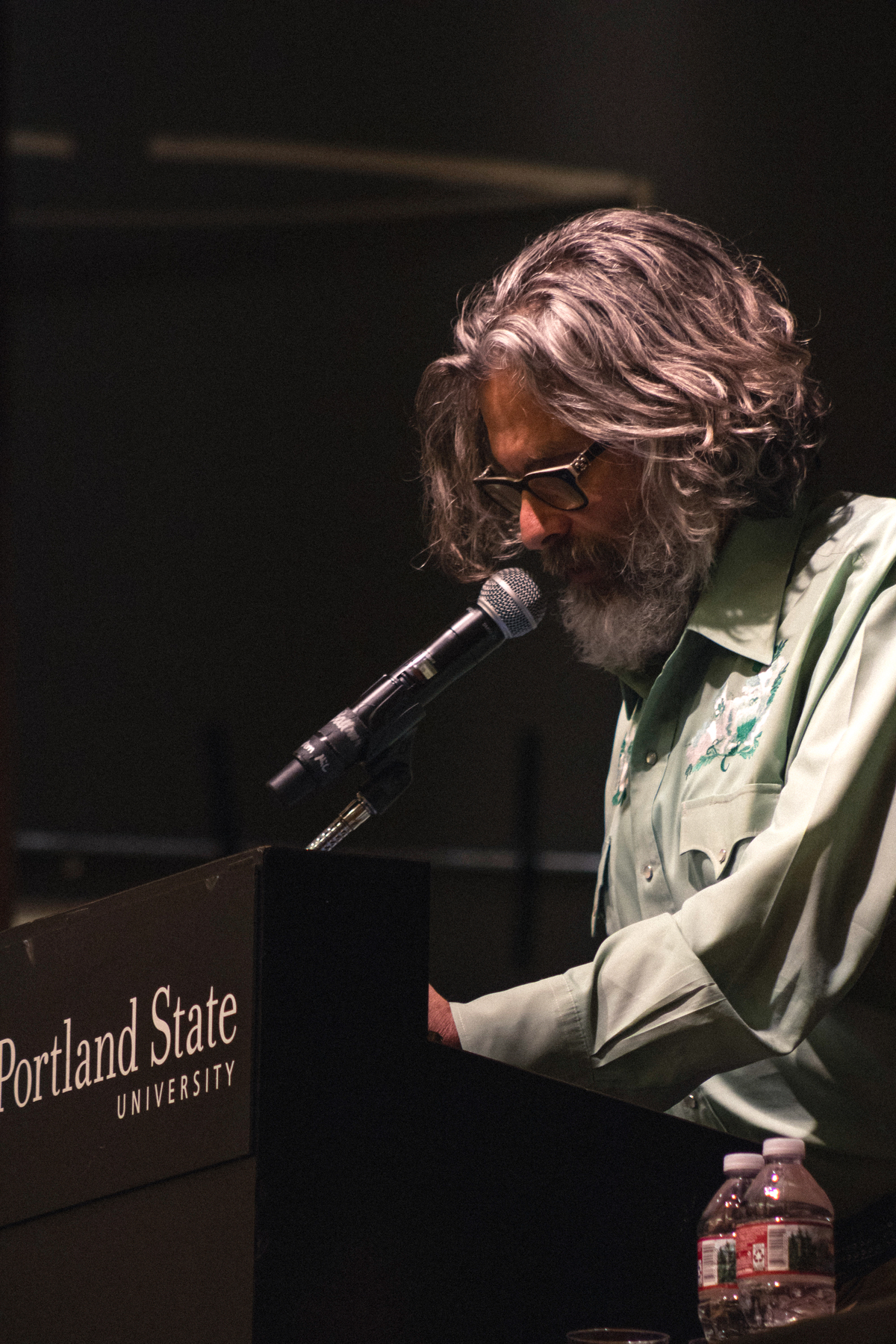

“It is important to note that the ICJ has not ruled on the merits of The Gambia’s complaint,” said Dr. David Kinsella, a professor of political science at Portland State, “but only on provisional measures that the Gambia has sought in order to safeguard the Rohingya Muslims.”

“The case is interesting because the Gambia really has no connection to the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.”

Although technically unaffected, the Gambia has argued that “any party to the Genocide Convention is, in a sense, harmed by genocide no matter where in the world occurs, and therefore [any] party to the Convention, such as Myanmar, has an obligation toward all, even the Gambia, whose population and territory are not directly affected,” according to Kinsella.

By accepting the merits of the case, the ICJ has set an important precedent regarding genocide cases, which the court rarely hears, according to Foreign Policy.

But some commentators noted that the court does not have the power to enforce its injunction. “Although the ICJ ruling is binding, the World Court does not have an enforcement mechanism, and Myanmar has not to date abided by any other international law or international humanitarian law (IHL) frameworks to prevent atrocities,” said Julie Norman, opinion contributor for The Hill.

Following the court’s ruling, Myanmar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs immediately issued a statement disputing key evidence presented in the case and denying genocide had occured. This follows the widely criticized denial of genocide by Myanmar’s leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, last December.

Kinsella noted that the court retains certain powers to ensure violence towards the Rohingya ceases. “Although it rarely happens, the UN Security Council may take measures to enforce rulings by the ICJ,” he explained via email. “If Myanmar does not implement the provisional measures ordered by the Court, the Gambia could request Security Council action, which may include military or non-military coercion.”

Still, some experts expressed reservations about whether or not the Security Council would actually make its presence felt in Myanmar. China and Russia retain the ability to veto Security Council operations, and both countries are broadly opposed to UN interventionism.

While geopolitical forces beyond Myanmar’s borders may limit the court’s ability to act unilaterally to defend the Rohingya, Kinsella said, “[Myanmar’s] government is on notice that the ICJ, and the world, is watching, and I can’t help but think that that’s progress.”