On the first Wednesday of the term—after a nasty debate and a long hot summer—what some of us needed was to just slow down and look.

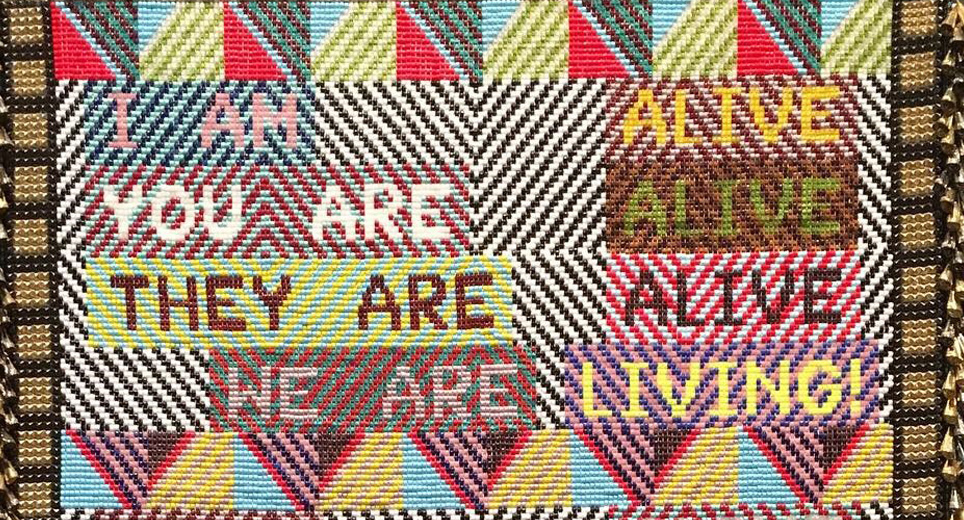

That’s what a group of 12 students did last week during a virtual Lunch and Learn, hosted by the University Studies Department for Viking Days. The artwork discussed is titled Alive! and is a beadwork piece by Brooklyn-based Choctaw artist Jeffrey Gibson. Alive! is a recent acquisition into the PSU collection and was commissioned for the university’s newest building on 4th and Montgomery.

Instead of rushing in with plaque-style trivia about the artwork and artist, Sarah Wolf Newlands, an assistant professor in the University Studies Department, tasked Zoom participants with describing the work before them in simple language as slides exposed it from various angles. Observations started appearing in the chat:

“Triangles, squares, chevrons, rectangles,” one participant wrote.

The chat read like a collective stream of consciousness, as participants chimed in with one-word phrases, such as “repetition,” tactile,” “horns” and “bells.”

Participants were intentionally left in the dark so they could create their own meanings, on their own screens and in their own rooms. This state of wonder—or uncertainty—is crucial to the learning process for Newlands.

“I love to center artwork in helping students build skills,” she said while introducing herself and her approach to teaching. “In doing this we discover how much we can learn by simply looking.” Newlands prompted students to spend time looking at the artwork and add words that describe it into the chat.

Yet even when details around the artwork’s origins started to pop up in the Zoom conversation, Newlands and her co-presenters resisted spilling the “beads,” waiting to offer any contextualizing details until the very end of the hour.

“[Often] when people go to museums they want to come to a conclusion about what something means,” Newlands said, “but the longer we hold something in observation, what we notice deepens.” By holding space for complexity, she prompted each person to come up with their own narrative.

This simple task takes on a layer of complexity, given that an aspect of what they were doing was incorporating an element of Indigenous cultural production into an academic context. The event, hosted by a panel of three white-passing people, has mostly drawn white or white-passing participants. Being asked to interpret meaning in this context feels like a slippery slope. How do a group of mostly white people go about making meaning of an Indigenous artist’s work? How do the BIPOC people in the group experience this process?

Professor Newlands’ intention is that participants will observe the formal qualities of this work as if they are keys that can contextualize Alive!—a work in which formal elements contain many threads.

Fluidity is a useful concept in constructing artistic meaning. Gibson is a queer, Indigenous man of Choctaw descent who grew up in Colorado, Germany and Korea and now lives in Brooklyn. Similarly, Gibson’s work resists singular, objective meaning and embraces hybridity.

As for the collective meaning arrived at via group observation, all this hybridity seems to reveal itself in the formal qualities of the work itself:

“It’s like Pac-Man,” someone said in the chat.

“[The] beadwork looks like grid work, very geometric,” another participant stated.

Beadwork, a common material in traditional Choctaw dance regalia, is woven with a pattern immediately recognizable to the virtual age. “Beadwork for powwow regalia is almost like the original pixel art,” said Native American Student and Community Center Manager Robert Franklin.

The beads themselves are like the ordinal systems of the computers through which these images appear—symbols that allow codes of meaning to emerge. These brightly colored beads are woven into two columns of words, making different phrases depending on the direction you choose to read. Follow the phrase left to right, and a series of statements emerge: “I am alive, you are alive, they are alive, we are living!”

If you read these statements column-by-column, the repetition begins to feel like a song or chant. Fittingly, the bell-shaped beads which adorn the piece’s edges hark back to jingle dresses—an iconic piece of powwow regalia.

It’s slightly surreal seeing Alive! just hang there, projected as a photo on a computer screen, soon to be in a frame on a white wall in an $104 million building. Given the deeply troubling imprint Oregon has left on families and tribes indigenous to the land where this artwork has been commissioned to sit, is it possible to find any true meaning in this work beyond the deeply sinister one implicit in the chant it offers us? Each person will have to decide for themselves.

Commissioned by PSU in 2016, Alive! will come to live under glass in the SW 4th and Montgomery building next month.