This piece is part of an issue with a content warning regarding police violence. For a full acknowledgement of the content warning and source anonymity, please visit our article: About this special issue.

Amid the nationwide college campus protests against the war in Gaza, comparisons are being made between these present-day movements and the student-led organizing that took place on the same college campuses during the Vietnam War. Many who partook in the Vietnam War protests are now commenting on the tactics and messaging used by today’s protesters. A question debated is, can these two moments in history truly be compared? The jury is still out.

Some 1970 protesters abhor today’s protesters, criticizing their motives as ignorant and their tactics as undermining a just cause. Still, others hesitate to lump today’s protesters—and each individual’s motives—into an all-encompassing amalgamation, i.e. “the protesters.” These conversations are being held all across the country. Given our notable history of war protests and occupation, Portland State is a good case to investigate the then-vs-now distinctions of the protests that have taken place and how onlookers discuss them.

With his arms linked in a line of student protesters and facing a wall of riot police, Doug Weiskopf yelled to his crew that, if they weren’t willing to be beaten or taken to jail, they ought to leave. It was May 11, 1970, and PSU students were on strike. Weiskopf was a primary organizer of the strike.

This came after months of continued presence by military recruiters on campus who faced pushback from the student body. The war in Vietnam continued, deaths on all sides were mounting and public support for the far-off war was collapsing, particularly among young people. When police opened fire on student protesters at Kent State, killing four and wounding more, student activists at PSU organized and began a strike.

Parallels lie in the lead-up to the protests that took place on campus starting in late April of this year. After Hamas’ massacre of Israeli citizens, their government began a widespread and indiscriminate bombing campaign against Hamas that has, up to now, left tens of thousands of Palestinians dead, many of them children.

The Israeli government’s tactics have been criticized around the world, least of all by the United States government, which continues to deliver arms to Israel. Though, as we go to print, President Joe Biden paused the shipment of bombs to Israel, citing concerns about their use in an offensive by the Israel Defense Forces in Gaza. Students at U.S. college campuses are among the most prominent critics of the war, and in April took to their campus quads to rally against the government’s continued support of the war.

At PSU—in 1970 and now—demands were made and evolved as the movement progressed. What was similar was that the demands were largely argued to be the “voice of the student body,” but didn’t necessarily capture the opinions of the majority. Back then, according to a student-created documentary about the protest, The Seventh Day (1970), a survey found that the majority of faculty and students weren’t against the university’s policy on military recruiting on campus. Today, student onlookers felt aggravated by the campus closures due to the protester’s presence. However, significant distinctions stand out.

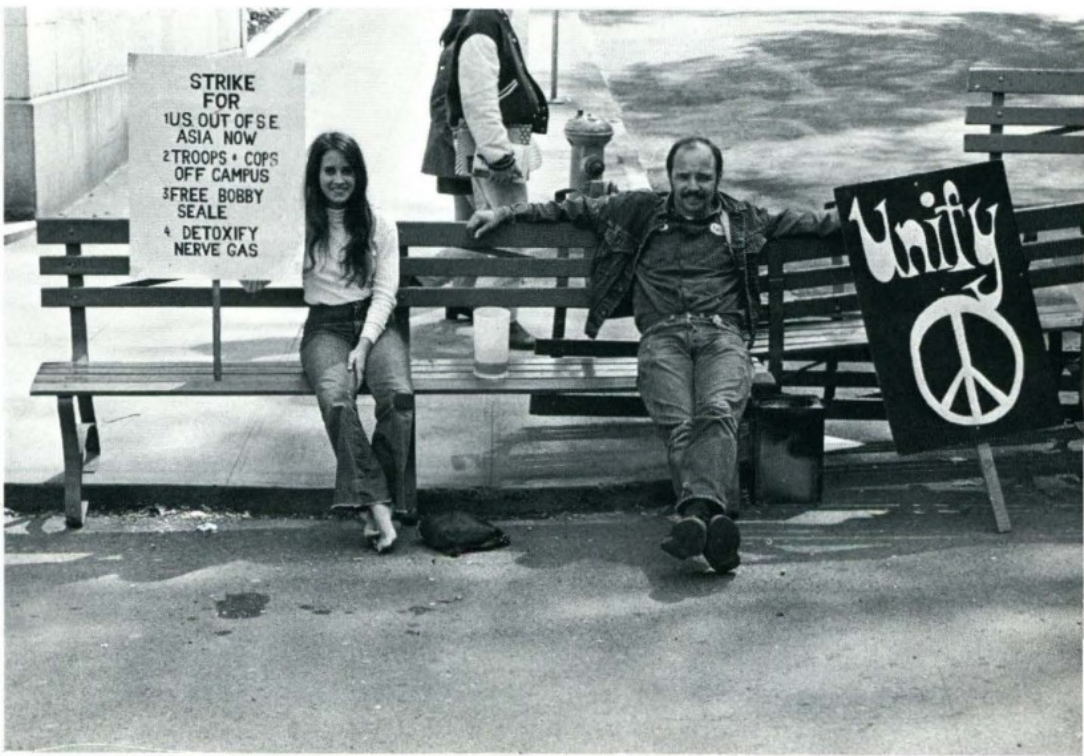

In 1970, the primary demand was that the university would bar military recruiters from campus, according to Weiskopf. Though, other student protesters had other demands entirely. Memorialized in a photo in 1970, a young woman can be seen sitting on one of the many barricades erected around campus. She holds a sign that lists not one but four demands: “1. U.S. Out of SE Asia Now; 2. Troops & Cops Off Campus; 3. Free Bobby Seale; 4. Detoxify Nerve Gas.” After riot cops came to campus and beat students, leading to several hospitalizations, the protesters added to their demands, specifically that the mayor disband the Tactical Operations Platoon, aka the riot police.

Today, protesters focused on pressuring the university to cut ties with Boeing. That expanded to other—and all—companies that do business with Israel. They also demanded that the university publicly denounce the war in Gaza. Eventually, this list expanded to 13 demands.

Building occupations were also a throughline. 1970 protesters occupied Smith Memorial Student Union (SMSU) as a de facto headquarters. “We were camped out in that building for a week,” said Weiskopf, the then-student organizer. “And there was talk of how we trashed the place, but no. There weren’t holes in the walls. There weren’t burnt carpets. There weren’t broken windows. There weren’t torn curtains. We left the place, and we cleaned up after ourselves after we left, as best as we could.”

Dr. David A. Horowitz—a Professor of U.S. Cultural and Political History who was present at the protest in 1970—corroborated this story. He remembered reports of vandalism in SMSU but said he had no firsthand knowledge of it.

The recent protesters also occupied a building on campus—the Branford Price Millar Library. Organizers Ember and Robin reported that the protestors had intentionally gained access to the library with the intent to occupy the space. Yet a rumor purported by a number of protesters was that the window was broken accidentally, and fearing retribution by the police, protesters entered the library ad-lib.

A major difference is that, in 1970, SMSU didn’t act as a fortress like the library was for protesters today. Also, the idea that damage occurred to SMSU at that time is questionable. The damage to the library is unquestionable. There was damage to the fire safety system, computer screens, television monitors and printers—a lot was destroyed or made unusable. Some protesters said that vandalism was intentionally used as a tactic to elucidate the importance we place on equipment over the lives of innocent Palestinians.

Still, others inside the library hadn’t intended for any of that to occur. In an on-screen interview with a local media outlet, one protester said that they broke down in tears when the vandalism was happening. “We want to respect your space as students and we’ve made sure that any damages incurred have been, you know, cleaned,” said a protester who went by James. “And from my understanding—again, this is just my understanding—funds are being [collected] to replace anything that [had been damaged by] the people who would come to tarnish our image.” In that way, James distinguished himself from fellow protesters or factions with different intentions.

James also maintained that the space was still open to everyone at the time of the occupation. Although, several library faculty said they weren’t allowed in at first. Or if they were allowed in, they were accompanied by an escort. Media was also allowed into the library but with an escort at all times. They were directed not to take any photos of individuals. Many who attempted to enter framed the occupied library as a hostile space. At one point, journalists with The Oregonian appeared to be chased out of the space and had water bottles thrown at their backs as they fled. Several people guarded the entrance at all times, asking prospective entrants who they were and what they wanted.

To be fair, I only saw this occur as the threat of police descending on the library became increasingly imminent. Some protesters were far more open to allowing anyone to enter. Later, after several belligerent individuals had been kicked out of the library, a protester spray-painted on the library wall, “No homeless allowed inside.”

Talk of outsiders was ubiquitous both then and now. Those commenting on the recent protests—including Portland State President Ann Cudd—have continually highlighted that nonstudents infiltrated them. James admitted that he wasn’t a student, but that student activists had invited him.

Several days later, when the first arrests were made, it was reported by the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) that only four of the 12 protesters arrested were students. Outside agitators also existed at the protest in 1970. According to Weiskopf, several high schoolers and other non-students came. According to him, “I pulled them all in and I said, ‘all right, these are the rules. No violence, no antagonizing people, no spray painting, no breaking windows, no trashing anything.’ They just nodded their heads, and they behaved themselves for the rest of the week.”

In both the 1970s and today, protesters resisted police presence on campus. On May 11, 1970, the Tactical Operations Platoon, a new group of police officers created to confront unrest, approached protesters after several days of protester presence on campus.

Cudd called PPB early on for the recent protests. Once the protesters had entered and occupied the library, she gave the police control of the situation. They didn’t come for several days—though drones purported to be operated by PPB could be seen flying above and around the library early on, surveilling the scene—but when they did, they looked similar to the Tactical Operations Platoon that attacked protesters in 1970.

There are some big distinctions between police involvement then and now. First, according to Weiskopf, the PSU President at the time told the cops they weren’t welcome on campus. The riot police began beating protesters despite his request for them to leave. Students were left bloodied on the street. Dozens were hospitalized.

Here and now, PPB only came after a few days of quiet. When they finally showed up, they surrounded the library and created a large perimeter. They entered from the back and began escorting protesters out in handcuffs. A few hours in, the protesters gathered on the portico and sprinted in different directions. One was knocked down as they ran and were arrested. When the cops went to drive those who had been arrested away, more protesters gathered and blocked the vehicles. The police then used what is believed to be smoke bombs, pepper spray and paintballs to push the crowd back in order to free the vehicles.

Eventually, the protesters gathered a block away from the library, linking arms. The riot cops created a line to keep them back and did so for several hours. After some hours, the library was secured with a fence. The police left, and protesters reentered the library shortly thereafter. The police then returned and arrested several more protesters.

The public’s response to the protests is strikingly similar, but disparities exist, too. At both protests, faculty members supported the protesters. However, there was also a heavy backlash against the protesters and their tactics. Weiskopf is among those criticizing protesters who occupied the library this past month, arguing that the violence used was self-defeating. He referred to the effectiveness of the non-violence used by his fellow protesters in 1970.

In 1970, protesters were wildly unpopular here in Portland and nationwide. Onlookers were interviewed as a part of the documentary The Seventh Day (1970). “I don’t like it one bit,” said one onlooker about the protest. “I just think that violence is a ridiculous way to do away with anything. These kids don’t know what they’re doing or what they’re thinking. I’m not for war. I’m completely for peace. But I don’t think these kids don’t know anything about anything.”

“I think this is a bunch of horseshit,” said another man in the documentary. “I think these guys are a bunch of kooks. I think [the cops] should run them all out.”

A woman, commenting on the marchers, said, “I think they’d get a lot further if the protesters cleaned themselves up and looked like clean Americans rather than dirty young men.”

But, at the time, there was also support. “I want to cry,” said one woman, having come down to the march after hearing about the attack on May 11, 1970. “I think it’s time the adults came forward and helped our kids. I think it’s time that we stop standing behind closed doors saying that they’re crazy and that they’re nuts, that they’ve got long hair and want to be radical. Sure, we know there are radicals in all of them, but my God Almighty, when are we going to step forward and start helping? When are we going to stop letting kids stand up here and fight this battle by themselves? I think it’s terrible.”

There are similar responses today. Many criticize the motives and the lack of context behind them. Others celebrate the fact that young people are standing up against violence perpetrated against innocent civilians in Gaza and supported by the U.S. government. A large difference in how the public reacted to protests now and then is the response directly after the major actions.

In 1970, after the students were beaten by police, thousands rallied behind them, marching to city hall and demanding that the mayor speak to what had happened.

Today, our campus is quiet. Protesters continue to rally, but there is no widespread public support. The focus is on the destruction of the library and the messaging that many see as verging on antisemitism. Still, many elders, faculty and onlookers recognize that their motives are in the right place.

One critic was Horowitz. A long advocate for peace in that region, he recognized that the protesters were correct in being appalled by the killing but that they were wrong in their messaging. “When you start to shame people on moral terms, then you yourself become the target of criticism,” Horowitz said. “And that’s one of the problems with the PSU demonstration and others. As other critics have pointed out, the protestors become the story, not the issues that are involved in the protest.”

Community members have consistently highlighted discrepancies between the movements in looking to the past to inform the present. Much of the messaging rejects the way things were done on campus these past few weeks and how the protesters’ actions are in stark contrast to the actions of protesters 54 years ago—yet similarities remain.

It may be too soon to have any semblance of finality—of distance—to allow an objective take on this year’s protests. Though derided at the time, the 1970 protests are now celebrated as having been a necessary step in ending an unjust war.

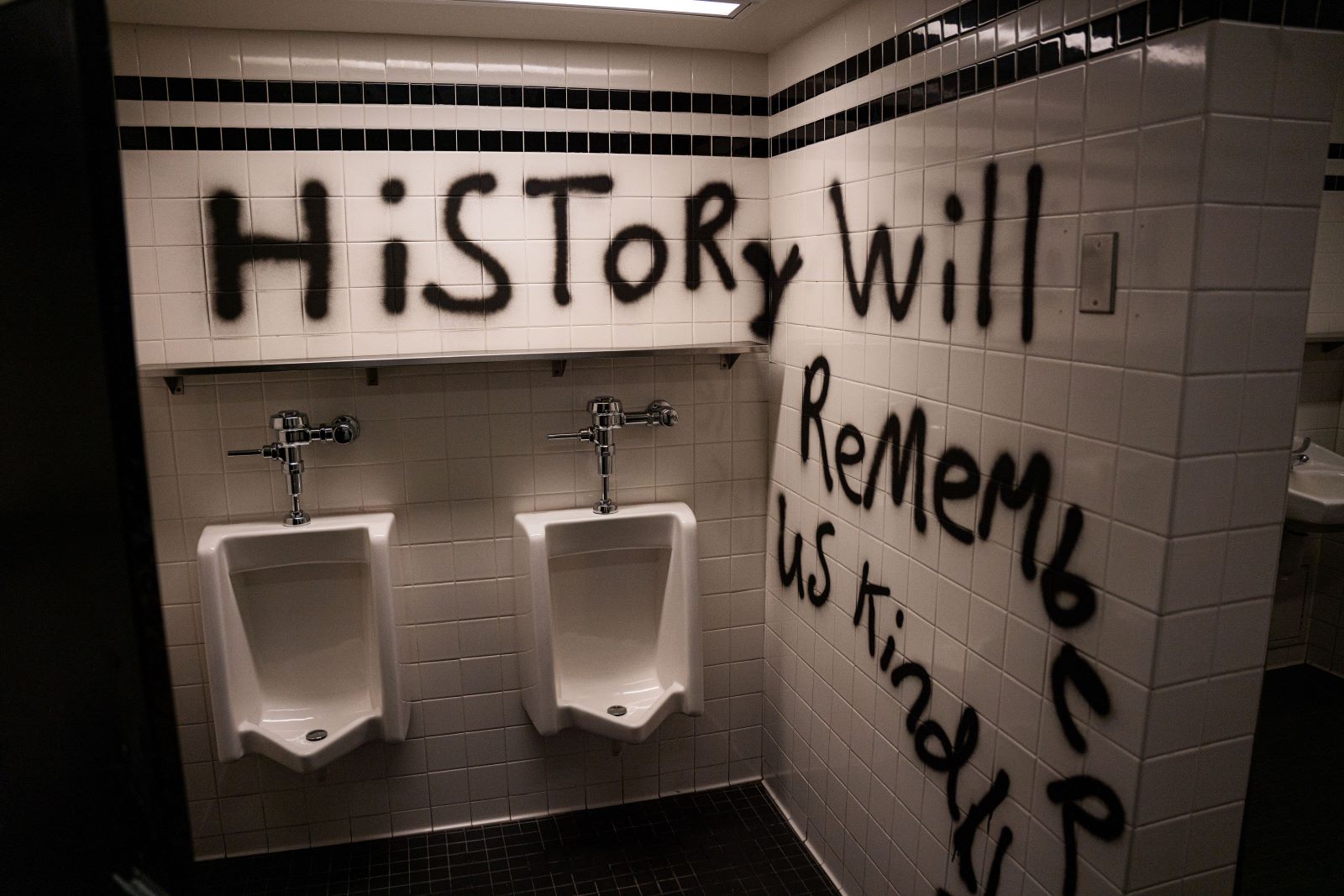

After the library had been cleared and workers were painting over the graffitied walls, I got the chance to walk through to survey the damage. Messages such as “Free Palestine” and “From the River to the Sea” blanketed the walls. After a while, the messaging became redundant. One, though, caught my eye. It was the words scrawled above some urinals in one of the bathrooms: “History will remember us kindly.”