Water is both a resource and a setting for recreational activities in Oregon. Even in the metropolitan area, you will see people swimming, floating, boating and kayaking on the Willamette river. With bodies of water playing a vital role in Oregonians’ day-to-day activities, we need to understand and mitigate the potential harms which could impact populations.

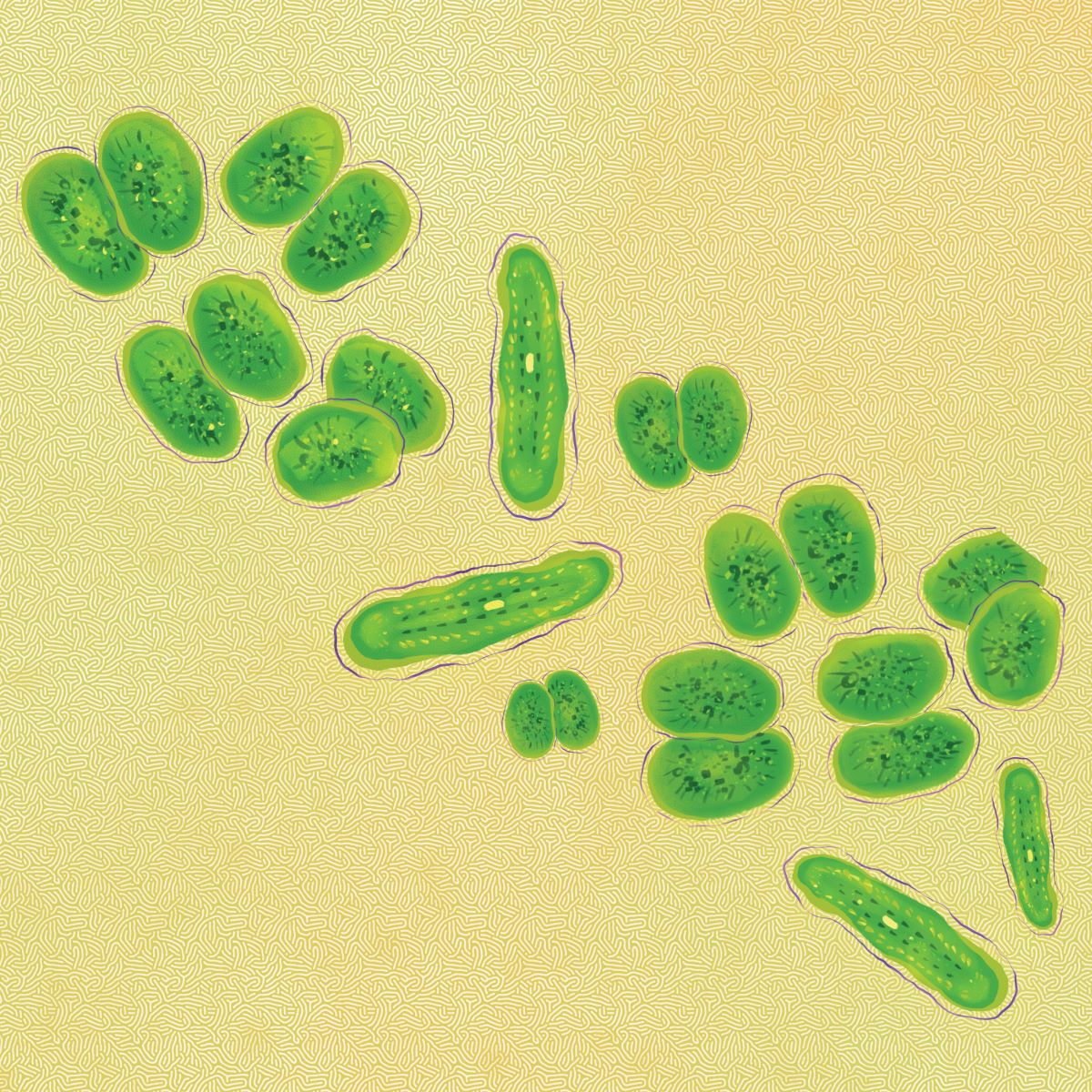

Algae blooms are a potential risk which can cause severe health issues when exposed to people, pets and livestock. We must understand what an algae bloom is to know the risk, though.

Algae can encompass a wide variety of life and potentially thousands of species. “We should not put a bad label on algae,” said Dr. Yangdong Pan, professor of environmental science and management at Portland State. “Only a handful of them can produce toxins and they can develop a very large population within a very short time period. Those are the troublemakers.”

These populations which bloom are often referred to in the science community as harmful algal blooms (HABs). Dr. Pan described the bloom as an “accumulation of a huge amount of biomass within a very short time period if the condition is favorable[…] then, some of those species have the capacity to produce toxins.”

The main HABs focus is often freshwater bodies in Oregon with blue-green algae—or more accurately, cyanobacteria blooms (CyanoHABs).

These blooms often occur when the conditions are favorable, cycling with a large bloom followed by a water ecosystem crash. These blooms have become more frequent and extensive in size, often taking longer to clear up here in the United States.

“The water column stability, too much nutrients, then a warm temperature—those are the main reasons why [HABs] are so abundant,” Dr. Pan said.

Some elements need global solutions—such as warmer temperatures—but others are a local problem which calls for a local solution—such as nutrient pollution.

“Phosphorus, nitrogen from agriculture, from our backyard, from [when] we put too much fertilizer [down and] the rain washes it into the water bodies,” Dr. Pan said. “Excessive amount of nutrients is something we can do [something about]. [It] requires watershed management.”

What classifies an algal bloom as harmful often depends on its effect with toxins being the main factor, since it directly threatens humans and animals.

“Cyanobacteria is very diverse, and they can produce toxins that do different things,” said Dr. Taylor Dodrill, a recent PSU environmental science Ph.D. graduate. “There’s toxins that affect your brain, there’s toxins that affect your liver, there’s toxins that just affect your skin, so it can take a lot of different forms—which is why I say it’s better to err on the side of caution.”

Dr. Dodrill also explained the risk from indirect contact with contaminated water. For example, the scum that washes up on the shore can often get onto dogs and livestock that tend to lick themselves, which can be fatal.

Another way HABs can cause harm is by depleting the oxygen in water, which can kill other living creatures and plants that rely on oxygen-rich water to survive.

“[When there is] a very dense form of biomass on top of the surface, what that does is because the bloom is constantly decomposing,” Dr. Dodrill said. “That decomposition under the surface drives down oxygen below the bloom, and that can create low-oxygen environments that can result in the killing of things like fish and other organisms if it’s really thick.”

Algae blooms can occur in marine systems and estuaries but present differently. “Most of the blooms we get on the Oregon coast, you can’t see them with your naked eye,” said Lara Jansen, a Ph.D. student in the earth environment and society program at PSU. “In freshwater, a lot of times you’ll see surface scum or something like that looks green, or it smells bad, but you don’t always get that in marine systems.”

People may only be aware of the risk they face with a visual cue, emphasizing the need to check government websites for potential HABs along the Oregon Coast.

This is especially true for people who collect shellfish along the coast. “These are mostly filter feeders, so they just take in water and are eating whatever particles come through to a certain extent, but then they also have the ability to, what’s called depurate, so they can excrete some of those toxins,” Jansen said.

As scientists continue to develop mitigation strategies and test solutions for reducing the size and frequency of these blooms, individuals can consult public advisories and closures to assess their risk of exposure.

Familiarize yourself with where you can find advisory information on any bodies of water you interact with regularly. For CyanoHABs, it’s good to know the visual signs. “Look out for very bright green scum on the water that is almost neon-ish or maybe even a golden color,” Dr. Dodrill said. “Generally, you want to look for a very strong coloration. It almost looks like paint slick. That’s when you should really be concerned because that means it’s very dense.”

It is essential to be aware of the visual cues of cyanotoxins, even if there is no advisory, as some bodies of water may not be regularly monitored or reported. Additionally, there are currently no filtration systems which can remove cyanotoxins from water.

Even if you’re not swimming, the water you interact with can still expose you to toxins. “Some misunderstand that when there’s a bloom that you can be safe if you’re boating, but there’s also an issue when you are boating—especially at high speeds—that can actually aerosolize the toxins,” Dr. Dodrill said.

“Some of [the HABs] are some of the most toxic by weight substances on earth,” Jansen said. “So they can really make you quite ill if you come into contact with them. So it’s good to check.”